A new study has reinterpreted a small copper-alloy object from Predynastic Egypt, identifying it as the earliest securely documented rotary metal drill in the Nile Valley. Dating to the late fourth millennium BC (around 3300–3000 BC), the artefact predates Egypt’s political unification and the rise of the pharaonic state.

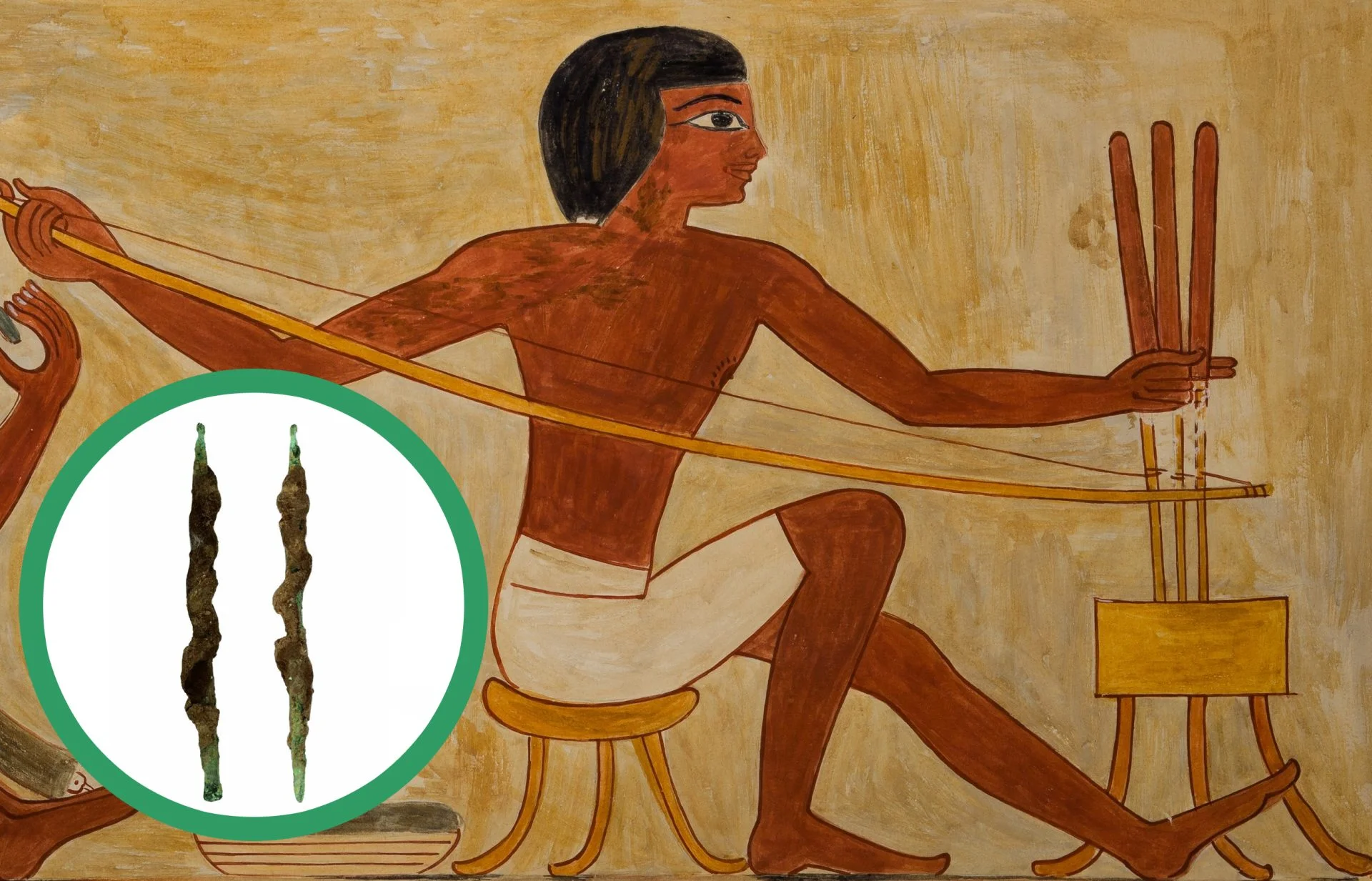

The piece was originally excavated in the early 1900s from Grave 3932 at the Badari cemetery in Upper Egypt. Now kept at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (catalogue no. 1924.948 A), it measures 63 mm long and weighs about 1.5 grams. When first reported in the 1920s, it was simply described as “a little awl of copper, with some leather thong wound round it,” a brief assessment that led to decades of limited scholarly attention.

An interdisciplinary reanalysis by researchers from Newcastle University and the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna has challenged that earlier identification. Microscopic examination revealed clear use-wear traces—fine circular striations, smoothed edges, and a slight curve at the tip—indicating prolonged rotary motion rather than straightforward piercing. These features strongly support its interpretation as a drill bit instead of an awl.

The team also reassessed six tightly coiled strands of extremely fragile leather wrapped around the shaft. They argue that these represent the remains of a bowstring, offering rare organic evidence for the use of a bow drill. In this mechanism, a cord is looped around a vertical shaft and driven back and forth with a bow, creating rapid rotation and greatly increasing efficiency and precision compared to hand-twisting.

Lead author Martin Odler, a Visiting Fellow at Newcastle University’s School of History, Classics and Archaeology, notes that while grand monuments and elite artefacts often dominate discussions of ancient Egypt, the technological systems that supported everyday craft production are less frequently examined. Drilling tools were essential for woodworking, bead-making, and stone carving—industries vital to both domestic life and elite craftsmanship.

Identifying this object as part of a bow drill suggests that Egyptian artisans had mastered mechanically assisted rotary drilling more than two thousand years before the better-preserved drill kits of the New Kingdom (mid–late second millennium BC). Bow drills are well documented in later periods, including tomb scenes in the Theban necropolis near Luxor that depict craftsmen drilling beads and wooden items.

Portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) analysis revealed that the artefact is made not only of copper but also contains arsenic and nickel, along with detectable amounts of lead and silver. This mixture would have produced a harder and potentially more visually striking metal than pure copper. The inclusion of lead and silver may indicate intentional alloying practices and points to participation in wider eastern Mediterranean exchange networks during the fourth millennium BC.

Beyond its technological significance, the study highlights the untapped value of long-held museum collections. An artefact briefly described a century ago has now provided important evidence of early metallurgical expertise and preserved rare organic remains that shed light on the working mechanics of Predynastic tools.