Tomb’s occupant confirmed to be a Tuyuhun king and the golden armour is likely to have been among his prized possessions, conservators say

“We will not leave the desert until we defeat the enemy, even if our golden armour is worn thin a hundred times.”

In this famous Tang dynasty poem, Wang Changling expressed the steadfast resolve of soldiers clad in golden armour as they fought on the empire’s desert frontiers.

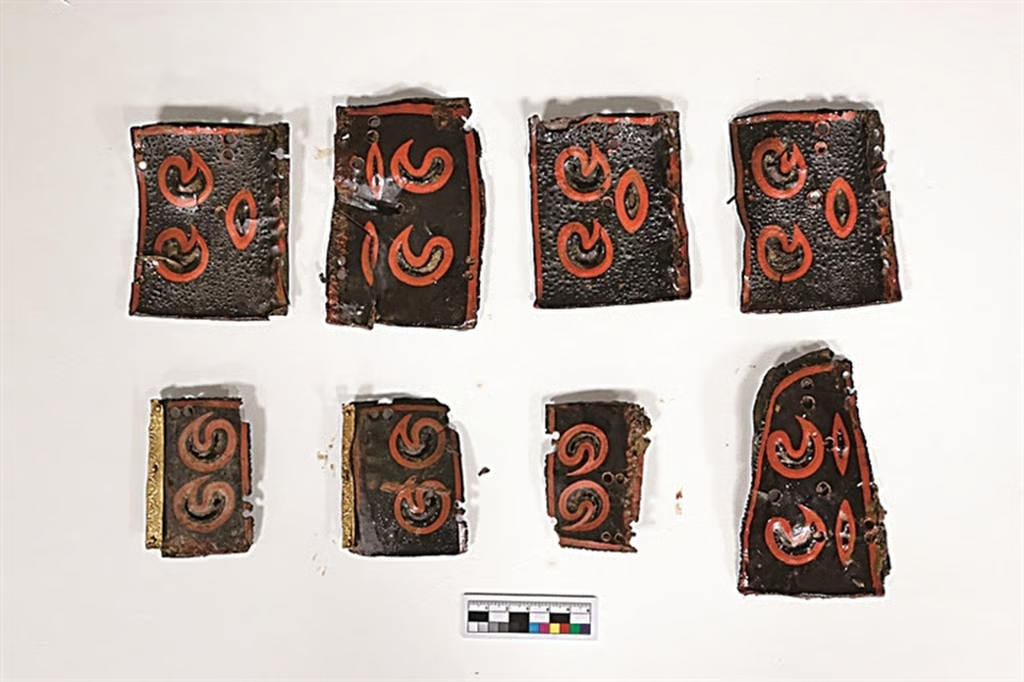

For centuries, however, the brilliance of Tang gold-plated armour existed only in literature and imagination, as no physical examples had ever been discovered. That changed last week, when the Key Laboratory of Archaeological Sciences and Cultural Heritage at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) revealed the only known surviving example of Tang dynasty “golden” armour—a carefully restored set of gilded bronze armour uncovered in a royal tomb on the Tibetan plateau.

The restoration team not only painstakingly reassembled the armour fragment by fragment, but also created a video reconstruction showing how it likely appeared in its original form.

The artefacts—including armour, lacquerware and metal objects—were recovered and restored from the Tuyuhun royal tombs between 2022 and 2025.

“At the core of our approach was breaking the whole into parts and then reconstructing the whole from those parts,” said cultural heritage conservation specialist Guo Zhengchen at a press conference held on January 14 to unveil the armour. “We carried out layered cleaning, extraction and preservation, while carefully documenting every individual armour plate.”

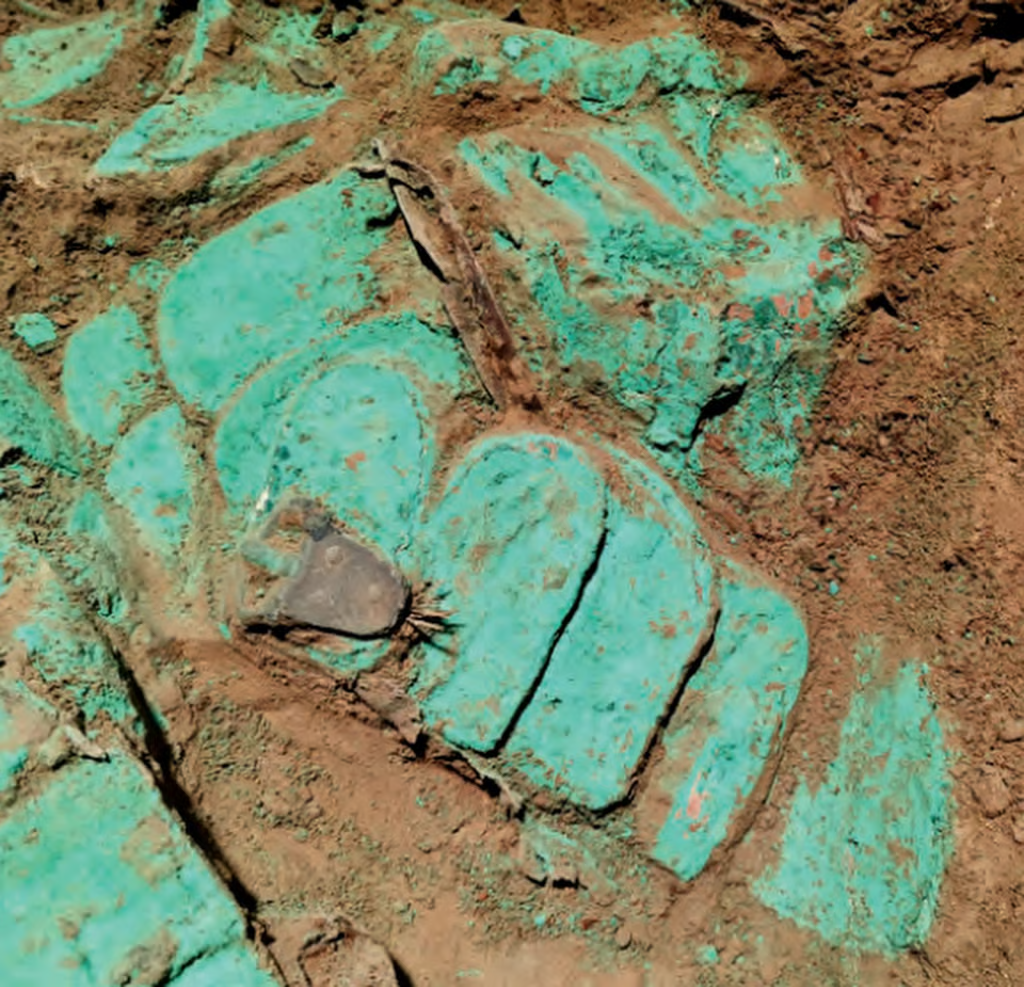

The royal tomb had previously been damaged by looting and salvage excavations, leaving the armour plates heavily fragmented and severely deteriorated. A 2024 excavation report published in the journal Archaeology described the discovery as follows: “Several bronze armour plates were uncovered … nearly rectangular in shape with a semicircular lower edge … along with a large quantity of lacquered armour fragments.”

The copper and lacquered pieces were found mixed together in piles, with no obvious structural arrangement. Extremely fragile, they risked breaking apart with even the slightest contact.

“To preserve crucial information, we recorded the original spatial position of each plate using 3D scanning and examined their production techniques and material composition through scanning electron microscopy and ultra-depth microscopy,” the conservators explained.

This analysis showed that the armour was not simply bronze, but gilded—confirming it as true golden armour. On the basis of this discovery, the team produced a detailed restoration video.

The reconstructed armour depicted in the video echoes another Tang dynasty verse: “Like golden scales upon the water, sunlight glints off our coats of mail.”

According to the conservation report, analysis of gold artefacts, silk textiles, and tree-ring dating of the tomb’s wooden structure places the burial in the mid-8th century.

The report confirmed that the tomb belonged to a Tuyuhun king, and the golden armour on display was likely among his most treasured possessions.

Once a dominant power on China’s western frontier, the Tuyuhun kingdom was gradually defeated by the Sui dynasty and later the Tang, before eventually becoming a vassal state of the Tubo empire on the Tibetan plateau. In addition to the golden armour, the tomb contained a wide range of equestrian equipment as well as iron and lacquered armour, providing valuable insight into the military culture of the era.

The discovery is consistent with historical accounts in the New Book of Tang, compiled by 11th-century historian Ouyang Xiu, which describes the Tubo as possessing “superior armour that covered the entire body, leaving only the eyes exposed, so that even powerful bows and sharp weapons could not cause serious injury”.

The tomb was located in Dulan County in northwestern Qinghai province, a key crossroads for east–west trade along the Silk Road.

The Qinghai route functioned as a crucial trade artery, connecting the Tubo empire and the Tang dynasty through a corridor that extended east to Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) and west to Xinjiang, Persia (modern Iran), and other parts of Central Asia.