A western European “water world” served as a refuge for hunter-gatherer communities for thousands of years.

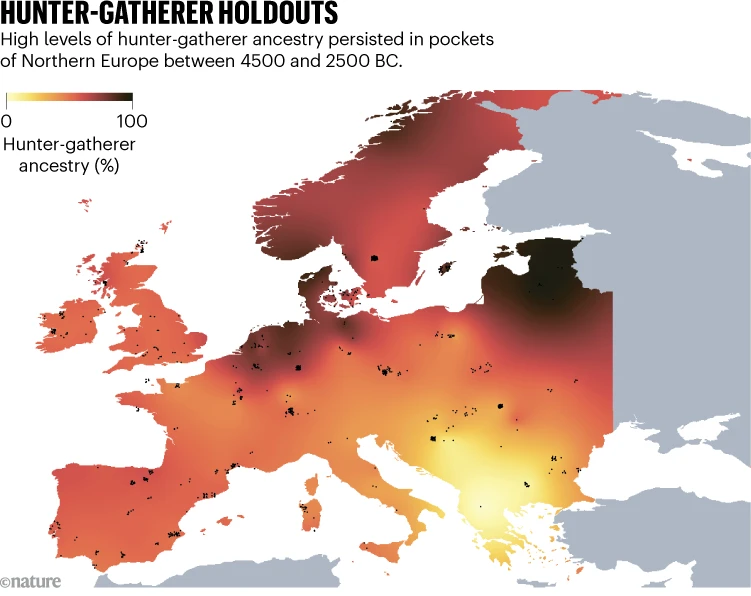

The ancient populations of the Rhine–Meuse river delta—covering the wetlands, rivers, and coastal regions of what are now the Netherlands, Belgium, and western Germany—retained a strong hunter-gatherer genetic heritage. This ancestry endured long after much of Europe had shifted to farming and livestock herding בעקבות waves of migration from the east beginning around 9,000 years ago. These findings were reported in a study published in Nature on 11 February.

“It’s essentially an island of continuity and resistance to outside genetic influence,” says David Reich, a population geneticist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and co-leader of the study.

Cultural integration

Over the past twenty years, ancient DNA research—including work from Reich’s lab—has outlined Europe’s population history over the last 10 millennia in broad terms. The research revealed that indigenous hunter-gatherers were gradually and unevenly replaced by farmers from the Middle East, who were later overtaken by pastoralist groups with roots in the Eurasian steppe.

However, researchers have long understood that closer regional analyses would provide more detail and uncover exceptions to this overarching narrative—something archaeologists in particular have anticipated.

Archaeological evidence from the Rhine–Meuse region had already indicated that hunter-gatherer ways of life continued there for a long time. However, the appearance of certain farming techniques, along with distinctive pottery and burial customs, pointed to at least some level of cultural contact with early farming communities and groups linked to steppe ancestry.

When Reich and his team examined ancient DNA from 112 individuals who lived between 8500 BC and 1700 BC—including newly analyzed remains from the region—they discovered that local populations preserved a strong hunter-gatherer genetic profile for thousands of years after it had largely vanished in nearby areas such as France, Germany, and Britain. The area’s landscape—made up of wetlands, wooded river dunes, and coastal zones—may have limited the spread of agriculture while fostering connections among water-oriented communities within the Rhine–Meuse delta.

The researchers also identified a gender imbalance in interactions between Rhine–Meuse hunter-gatherers and incoming groups. Analysis of genetic variation on the X and Y chromosomes suggested that ancestry linked to early European farmers was introduced mainly through women.

“We believe that elements of the farming lifestyle adopted by these hunter-gatherer communities were brought in through these women,” said co-author Eveline Altena, an archaeogeneticist at Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands.