In the summer of 2020, researcher Walter Crist was exploring a Dutch museum focused on the Roman Empire’s presence in the Netherlands when one artifact caught his attention. Crist, who specializes in ancient board games, noticed a small stone game board from the late Roman period. About eight inches wide, it featured angular lines forming an oblong octagon within a rectangle—an unfamiliar design he had never encountered in academic literature.

Neither the game’s name nor its rules were known. Curious, Crist reached out to museum curators for closer access. He and his colleagues have since proposed a solution in a groundbreaking study that combined traditional archaeological analysis with artificial intelligence. Their findings suggest the board was used for a “blocking game,” in which one player attempts to prevent the other from making moves—similar in concept to tic-tac-toe. The study was published Monday in the journal Antiquity.

Now a guest lecturer at Leiden University, Crist explained that the team initially had limited information. The board had been discovered in the late 19th or early 20th century in Heerlen, in the southeastern Netherlands—known as Coriovallum during Roman times. It was carved from limestone imported from France. Researchers believe the game was likely played informally and may not have been especially prominent, as no written records from the period mention it.

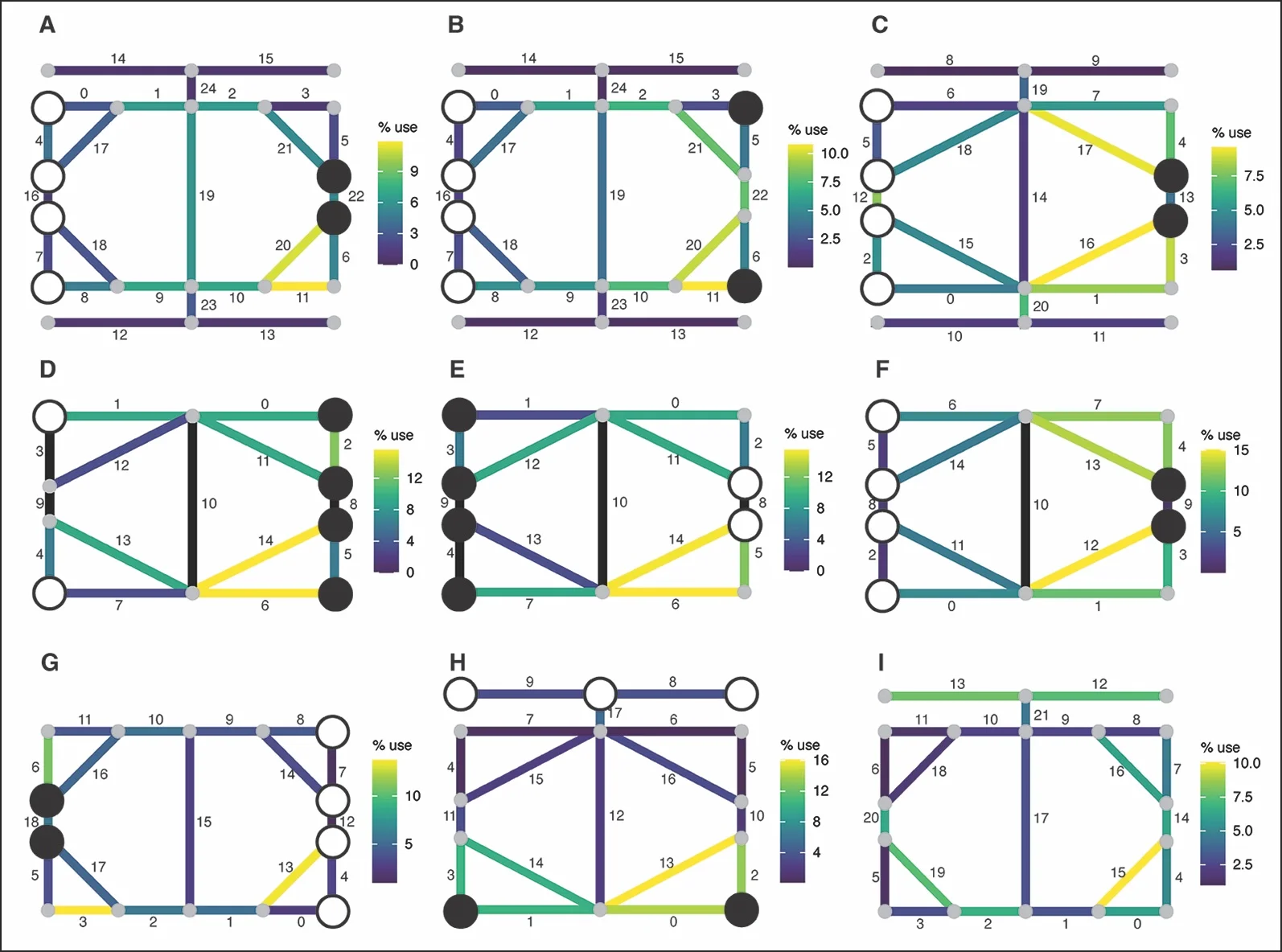

Results of the AI simulation showing nine possible game boards. In these games, the player with more pieces attempts to block the player with fewer pieces.

Crist believes the findings could assist scholars in interpreting other ancient board games. He notes that such games create a meaningful link between the past and present, as their core mechanics have remained remarkably consistent over time. For instance, the ancient Egyptian game Senet may not have been entirely unlike modern games such as Sorry!. Chess is widely believed to have originated in ancient India, while the exact origins of backgammon remain uncertain.

By reconstructing how these early games were played, Crist says researchers can gain fresh perspectives on leisure, strategy, and everyday life in the ancient world.