An Enigmatic Papyrus from El-Amarna: A possible Egyptian representation of Mycenaean warriors

Egypt, the cradle of ancient civilizations, has provided a constant stream of archaeological riches that never fail to bewilder us. The city of El-Amarna, the short-lived capital established by the heretic Pharaoh Akhenaten, is a prime source of these treasures. The latest discovery is a rare papyrus that has captured the attention of scholars worldwide. The papyrus could possibly represent Mycenaean warriors, providing an intriguing new perspective on Bronze Age Mediterranean connections.

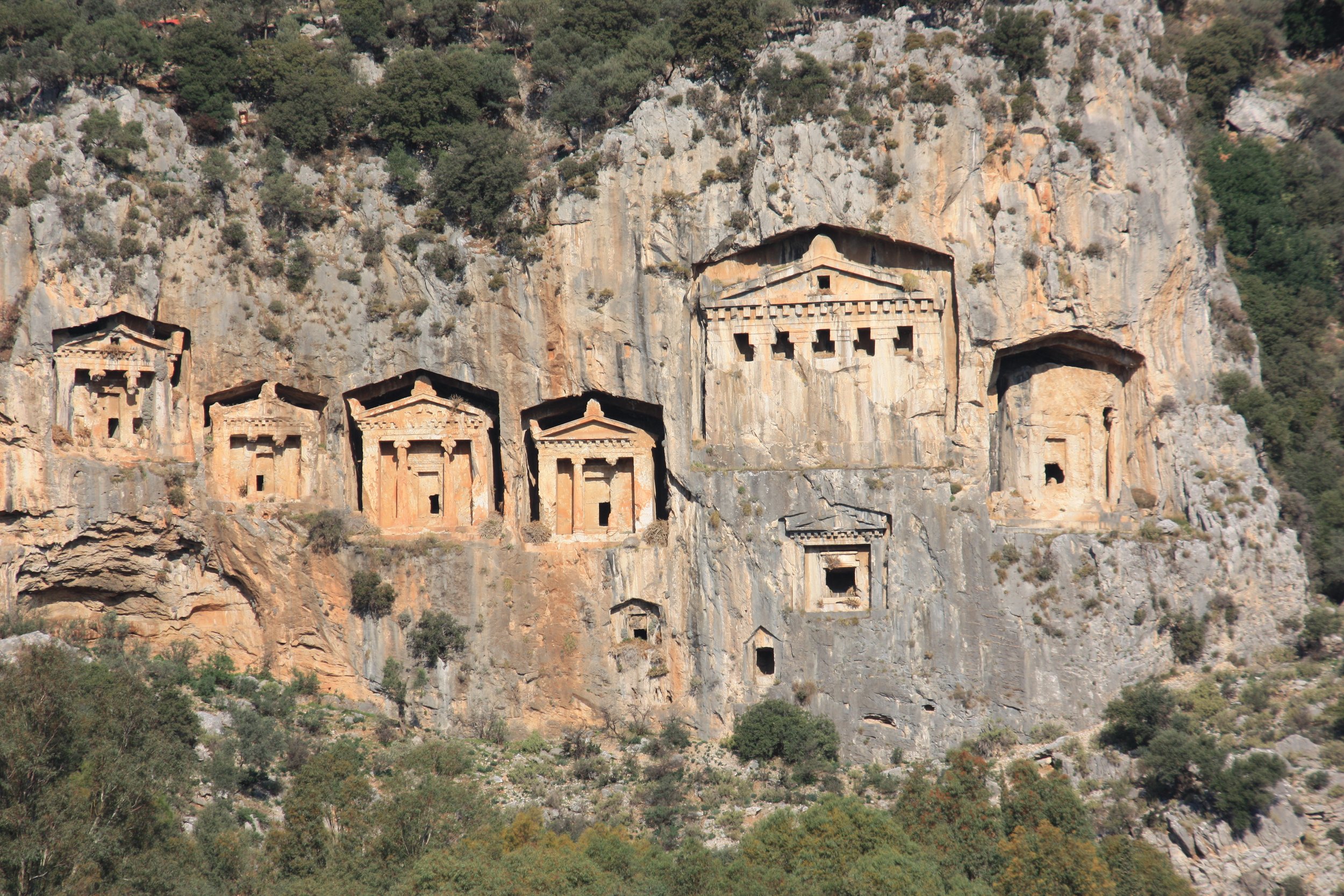

An Unusual Discovery

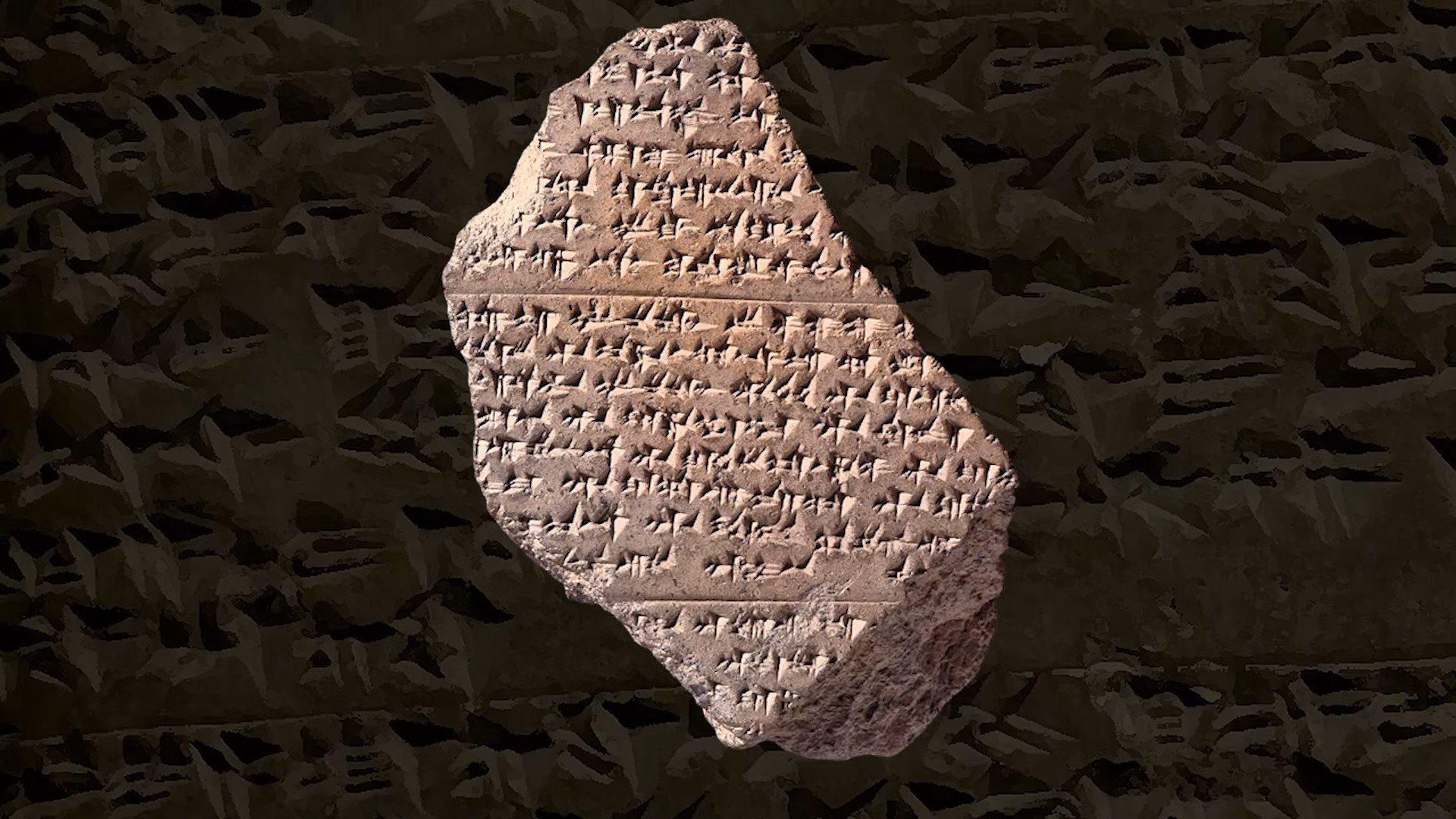

Unearthed during a recent dig at El-Amarna, the papyrus was found to be remarkably well preserved, thanks to Egypt's dry climate. The intricate hieroglyphics and vivid colors attest to the craftsmanship and sophistication of Egyptian scribes during the Amarna period (1353–1336 BC). Yet the true fascination lies not in the artistry but in the content: the papyrus depicts warriors bearing an uncanny resemblance to those from the Mycenaean civilization.

Those papyrus fragments, dated to the second half of the 14th century BC and currently being exposed in the British Museum, depict battle scenes between Egyptian and Libyan soldiers. In one of those fragments, we can see warriors bearing the typical Mycenaean Boar-tusk helmet and Egyptian or Aegean-style short-cropped oxhide tunics running on the battle front.

These can be paralleled in representations from the Aegean, suggesting that the painting may show figures wearing boar's tusk helmets and Mycenaean-style tunics. This interpretation of the battle scene argues that the Egyptian iconographic repertoire also included depictions of Mycenean features and adds to the evidence for direct, rather than indirect, contacts between the two cultures.

Fragments of two scenes of the painted papyrus, without text. One shows a fallen Egyptian overcome by a Libyan, while other Libyan archers rush on. The second shows registers of Egyptian infantrymen, some wearing helmets and/or short ox-hide tunics. Other unplaced fragments show parts of further infantrymen, and a tree. The scene includes other indications of landscape. The British Museum.

A Mycenaean Connection?

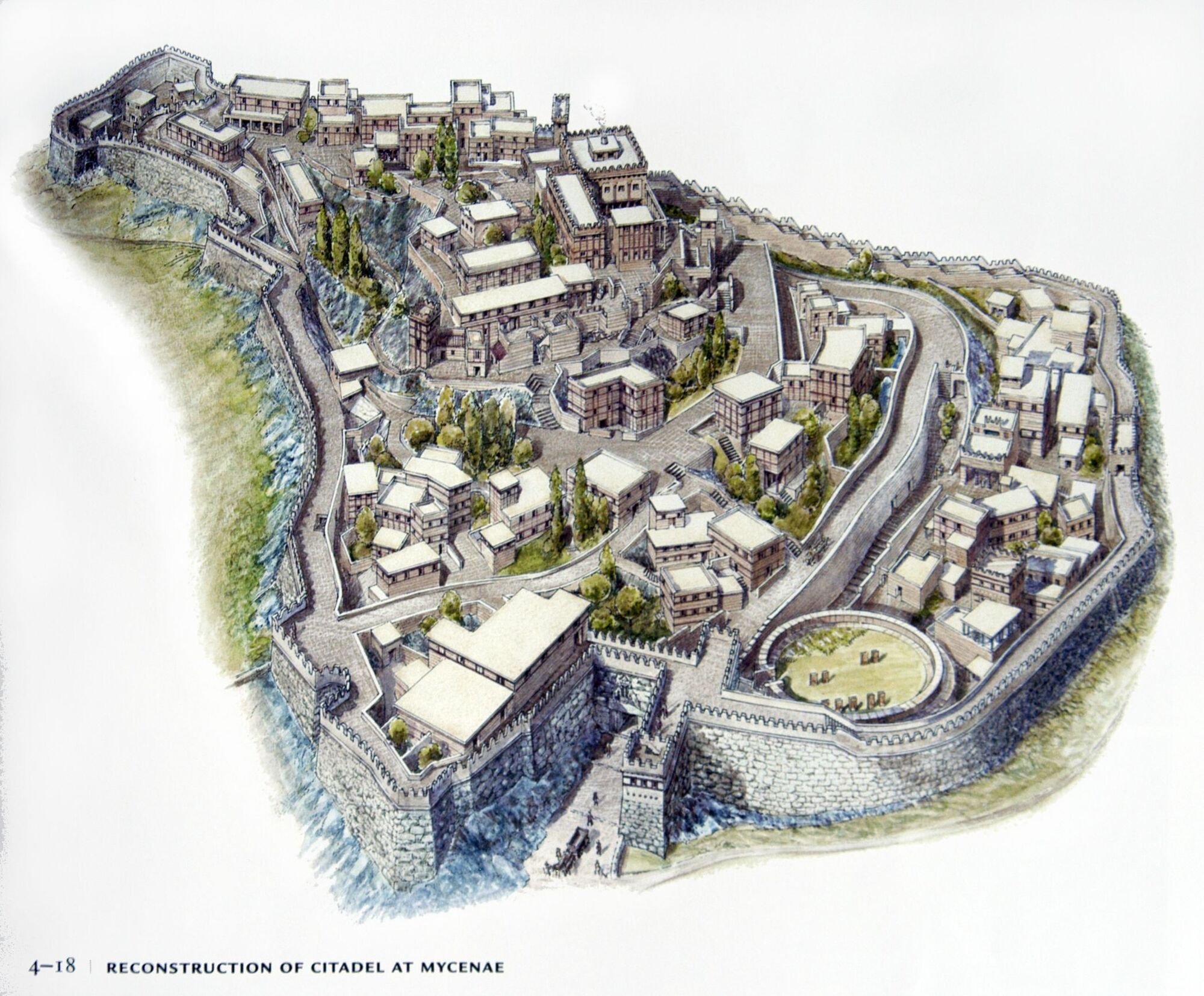

The Mycenaean civilization, centered in the Peloponnese of modern-day Greece, thrived during the Late Bronze Age (1600–1100 BC). Their warrior-centric society, chariot warfare, and iconic "boar’s tusk" helmets were immortalized by Homer's epic poems.

In the papyrus from El-Amarna, the warriors are illustrated with short, wavy hair, round shields, long spears, and distinctive helmets. The physical attributes and weaponry closely resemble Mycenaean depictions, particularly those found in frescoes from Pylos and Mycenae. Intriguingly, the possible representation of "boar's tusk" helmets, a Mycenaean hallmark, raises questions about the nature of the interaction between the two civilizations.

Cultural Interactions in the Bronze Age

During the Bronze Age, civilizations around the Mediterranean Sea, including the Egyptian and Mycenaean, established complex networks of interaction. This era saw significant trading, diplomatic exchanges, and, inevitably, warfare. Excavations have found Mycenaean pottery in Egypt and vice versa, proving the existence of trade relations.

Moreover, the Amarna Letters—a cache of clay tablets from the 14th century BC—provide evidence of diplomatic correspondence between Egypt and states in the Aegean, possibly including the Mycenaeans. But depictions of Mycenaean individuals in Egyptian artifacts are rare, making this papyrus potentially ground-breaking.

Illustration of a Mycenaean Greek warrior with the distinctive boar-tusk helmet at the fall of Troy

Implications of the Papyrus

If the interpretation of the papyrus holds true, it could signify that the Mycenaeans had a more substantial presence or influence in Egypt than previously thought. The warriors could represent mercenaries, allies, enemies, or simply a demonstration of cultural knowledge. The pictorial representation suggests a more direct interaction, implying that the Mycenaeans were not just abstract entities in Egyptian perception but had a tangible presence.

This discovery could be a step towards recognizing a previously unknown degree of interconnectedness between the Bronze Age civilizations of Egypt and Mycenae. As scholars continue to investigate, this enigmatic papyrus will serve as a tantalizing puzzle piece in the vibrant mosaic of Bronze Age history.

The Mycenaean boar-tusk helmet

The distinctive Boar-tusk helmet of the Mycenaean warrior elite could be a strong evidence of the presence of those fearsome Aegean warriors in the plains of Egypt, supported also by the large quantities of Mycenaean pottery that have been also found in El-Amarna, in the same period. Both evidence suggest some degree of cultural contact between the Mycenaeans and the Egyptians of the Late 18th Dynasty.

Mycenaean helmet with wild boar teeth

The so-called ‘odontophracto’ helmet is considered a Mycenaean invention and was a basic part of the armor, at least until the 13th century.

According to the Homeric description, the helmet consists of the "kynei", a dog's skin leather cap with a wool lining, which is protected by superimposed rows of specially worked boar's teeth.

Mycenaeans seem not to have been included amongst the Egyptians' repertoire of depictions of foreigners, although Minoans clearly identified on many Egyptian frescoes, such as those on many tombs and temples (tombs of Anen, Rekhmire, Puimre, Senenmut, Menkheperrasoneb, Abydos Temple of Rameses II).

We also know about the close involvement of Minoan Crete in international relations and cultural exchanges with the Eastern Mediterranean and Egypt either through marriage, art, technology or exchange of gifts (Minoan frescoes at Tell El-Dab'a).

Distant theaters of royal action in the Bronze Age: The international policy of the pharaohs and the ‘Aegean List’

The usage of professional warriors from the Bronze Age (some of them of Hellenic origin) can be safely assumed as the complete retails of the organization and structure of the period armies are not quite clear to us. The employment of mercenaries cannot be excluded in the early Bronze Age but it becomes certain in the later stages. It is also known that earlier Aegean armies and navies, such as the Minoans, used mercenaries from Africa.

We do know that after the Egyptian Pharaoh Rameses II (r. 1279–1213 BC, about one century after the El-Amarna papyrus) defeated the Sherden sea pirates at the beginning of his reign, he hired many of them to serve as his bodyguard. It has been suggested that some of them were from Ionia. In the reign (1213–1203 BC) of his successor Merneptah, Egypt was attacked by their Libyan neighbors, and some experts believe that the Libyan army included mercenaries from Europe’s mainland. Among them were people termed ‘Ekwash, and it has been proposed that this meant Achaeans (Mycenaeans), but there is no certainty of that as other evidence points to an attempted encroachment by Libyans only upon neighboring territory.

The fresco ‘Captain of the Blacks’ at Knossos, thought to represent a Minoan officer with two spears, leading a troop of Nubian mercenaries, Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete, Greece.

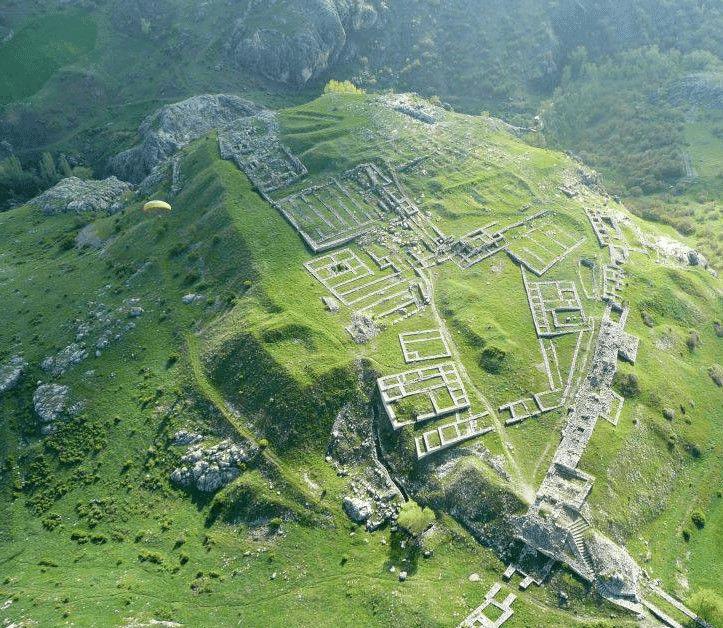

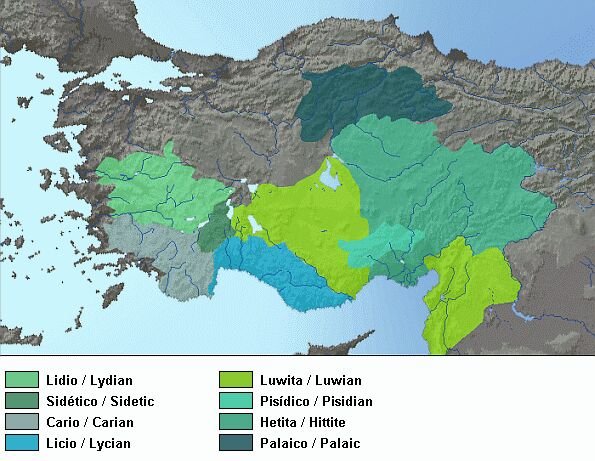

Another important indication of the developed relations between Egypt and the Aegean is the famous "Aegean List" of Pharaoh Amenhotep III, an inscription of toponyms found at the base of a statue in the northern half of the West Portico of the great Peristyle Court in Kom el-Hettân, which seems to refer to areas and nations of the Aegean that were probably visited by an Egyptian merchant or diplomatic mission.

Each statue base bears a different series of toponyms written within “fortified” or “crenellated” ovals and superimposed on bound captives—a standard Egyptian way of denoting foreign places. Together, they represent roughly half of the known outside world.

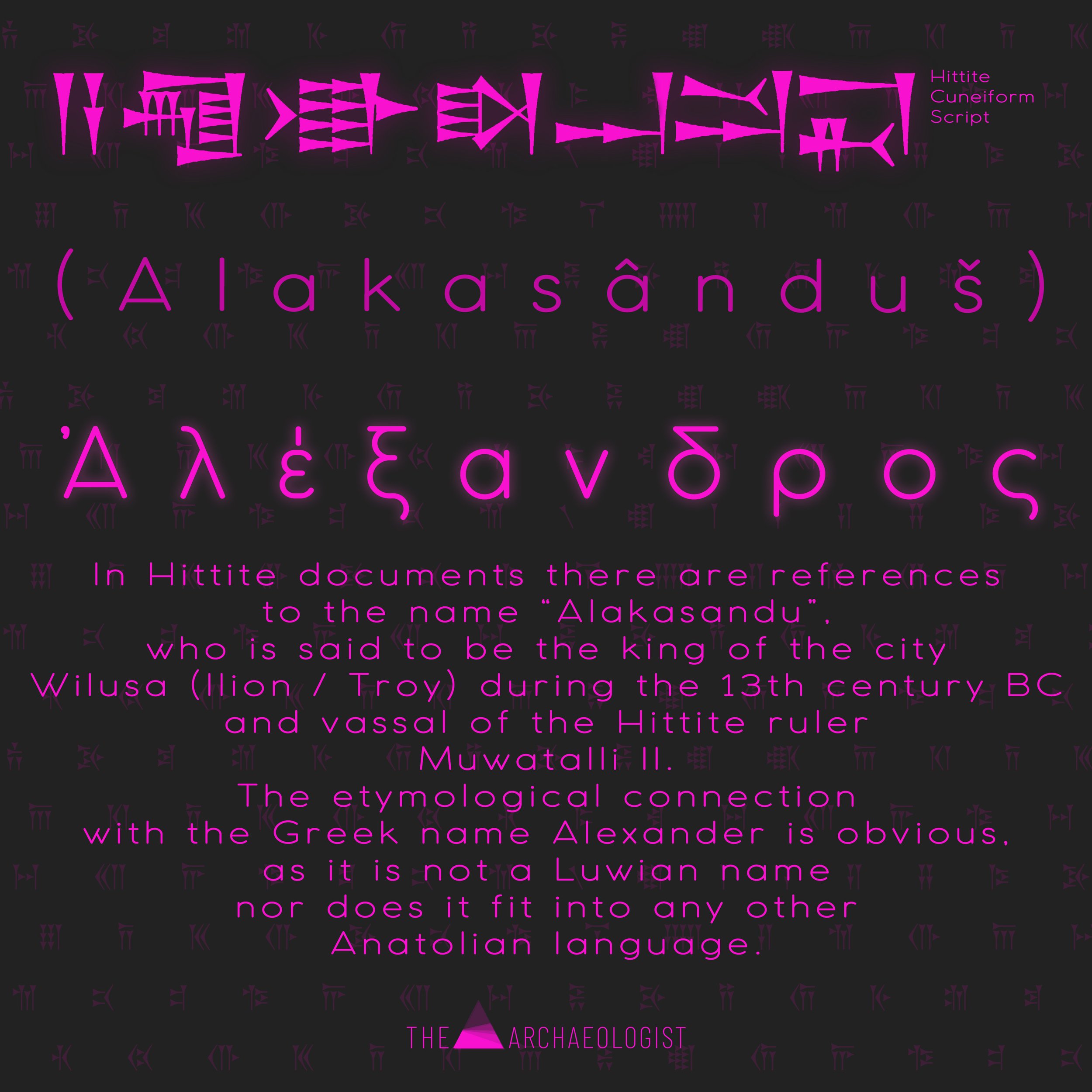

The order in which the toponyms are to be read is crucial. In the center of the front side, two bound prisoners support Amenhotep III’s prenomen and nomen. The two place names to the right should be read first, since they face the same direction as these cartouches; they are kftiw, i.e., Keftiu, identified as Crete, and tny (ti-nA-y-w), i.e., Tanaja (Danaia, the Danaoi-Land, meaning the land of Danaans, the homeric Achaeans), identified as mainland Greece. Both are known from other Egyptian sources from the time of Thutmose III onward, and their identification is accepted by most scholars.

The Aegean List’s other toponyms are unique; not one of them appears in any other Egyptian source, either before or after Amenhotep III’s reign. All scholars agree that these names denote sites and regions in the Bronze Age Aegean, but their identification is sometimes challenging. Some of them are translated as Amnisos, Phaistos, Knossos, Lyktos, Kydonia, Mycenae, Pisaia, Kythera, Methara, or Messana(?), Thebes, Tegea, or Dikte(? ), and Eleia, or Ilios (Troy)(?).

The Aegean List remains of critical importance as a clear indication that the Egyptians had substantial knowledge of specific Minoan and Mycenaean sites during Amenhotep III’s reign.

The extroverted and aggressive Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt

The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt is classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty spanned the period from 1550/1549 to 1292 BC. This dynasty is also known as the Thutmosid Dynasty after the four pharaohs named Thutmose.

The Eighteenth Dynasty empire conquered all of Lower Nubia under Thutmose I. By the reign of Thutmose III, the Egyptians had directly controlled Nubia up to the Nile River, the 4th cataract, With Egyptian influence and tributaries extending beyond this point. The Egyptians referred to the area as Kush, and it was administered by the Viceroy of Kush. The 18th dynasty obtained Nubian gold, animal skins, ivory, ebony, cattle, and horses, which were of exceptional quality. The Egyptians built temples throughout Nubia.

After the end of the Hyksos period of foreign rule, the Eighteenth Dynasty engaged in a vigorous phase of expansionism, conquering vast areas of the Near East, with Pharaoh Thutmose III submitting the "Shasu" Bedouins of northern Canaan and the land of Retjenu, as far as Syria and Mittani, in numerous military campaigns circa 1450 BC.

The El-Amarna papyrus presents a captivating glimpse into the cross-cultural encounters of the ancient world. As the world waits for more comprehensive analyses and potential verification of the Mycenaean representation, the papyrus holds its secrets close, reminding us that history often reveals itself in fragments and whispers rather than in complete narratives or loud declarations. Its tantalizing hints of an interlinked Mediterranean world make the papyrus an invaluable addition to our understanding of the vast tapestry of human history.