Medinet Habu, the severed hands of the defeated enemies

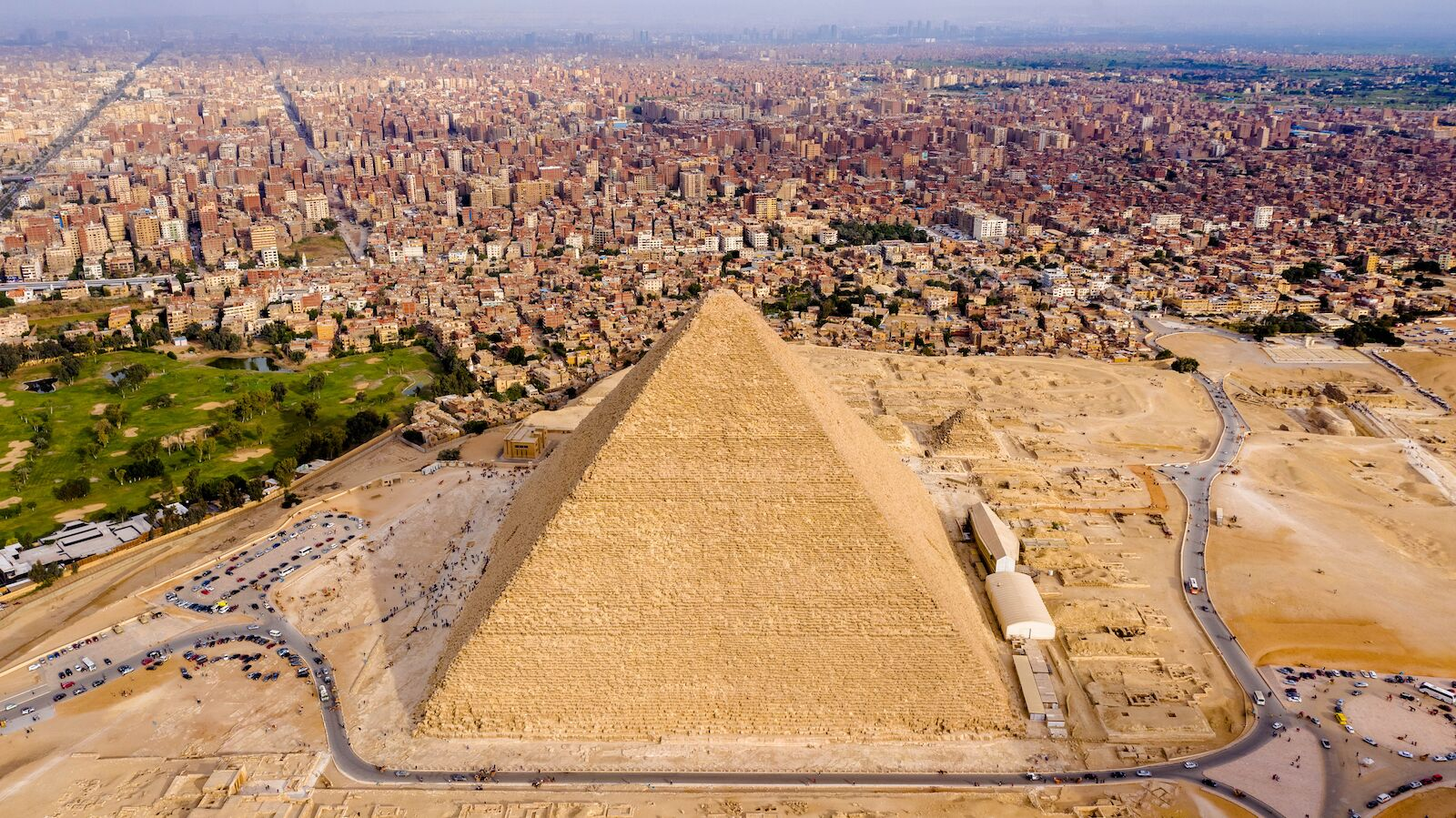

Usermaatre Meryamun, better known as Ramses III (1184 – 1153 BC), was the second and most important king of the Twentieth Dynasty (1186 – 1069 BC).

The particularities of his extensive reign, the significance of his military victories against the so-called “Sea Peoples”, and the magnificent state of preservation of his funerary temple in Medinet Habu (Western Thebes) made him one of the most important pharaohs of all the period of the Egyptian New Kingdom (approx. 1550 – 1069 BC).

Ramses III, the warrior king

The reign of Ramses III developed in a temporary context in which dangerous threats existed on the Egyptian borders. And this despite the fact that the new king had benefited in his first five-year reign from the peace and stability inherited from his father, Setnakhte (1186 – 1184 BC).

Already in the fifth year of reign he had to face the new advances of the western Libyan tribes, who had taken advantage of the instability and political decomposition of the last kings of the Nineteenth Dynasty to penetrate the western Delta until reaching the main branch of the River Nile.

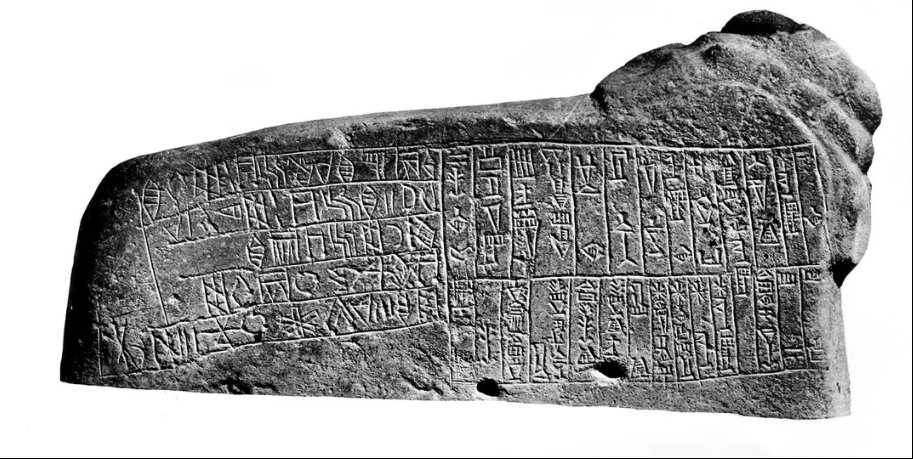

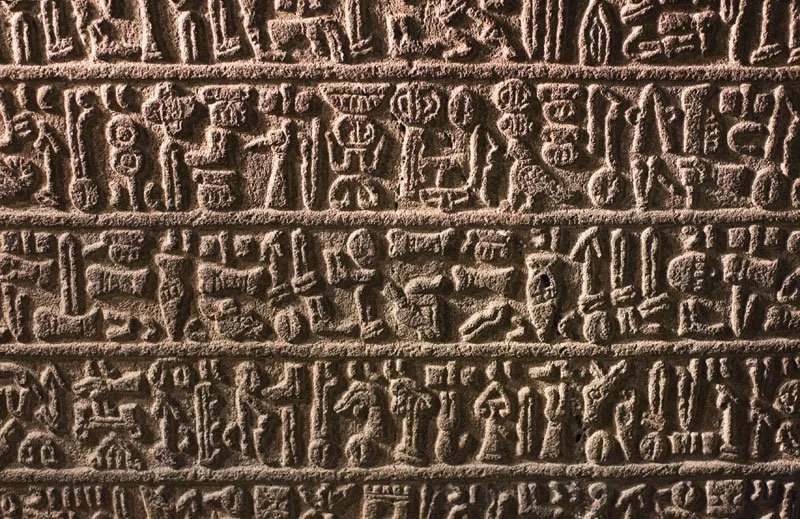

The battle that took place that year (approx. 1180 BC ) between the two armies marked the first major military success of Ramses III, and was thus represented in a large inscription made on the walls of the second courtyard of the Medinet Habu temple.

However, the euphoria would not last long, as a new Libyan campaign – also victorious and also represented in the temple – occurred six years later, in the year 11 of the reign of Ramses III.

Relief of Ramses III defeating his enemies at Medinet Habu

Ramses III, Egypt and the Sea Peoples

Beyond these Libyan wars, the greatest military challenge Ramses III had to face during his reign was the war waged against the so-called “Sea Peoples” in the eighth year of his reign.

The situation was much more serious if we take into account that it was not just an army invasion, but rather a massive and sudden migration of heterogeneous displaced peoples seeking to settle in the areas they attacked, thus taking their families with them.

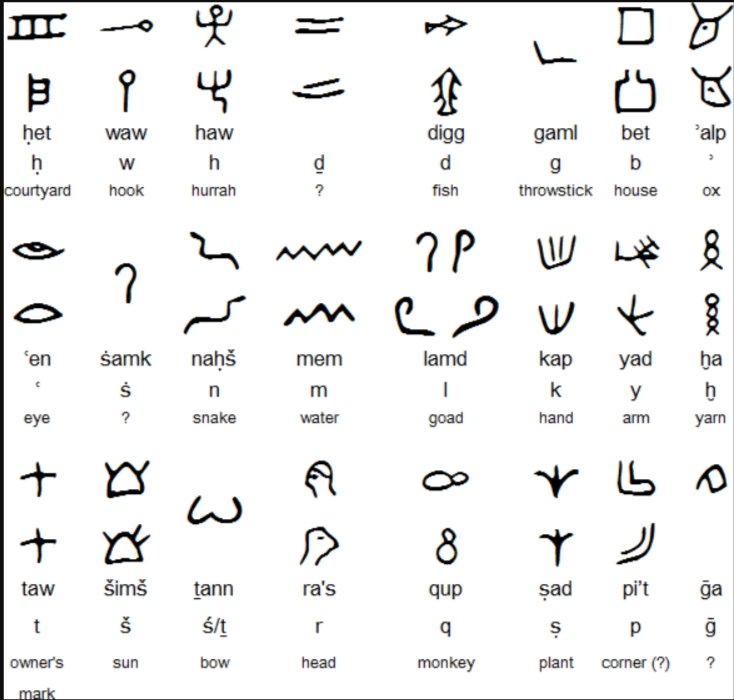

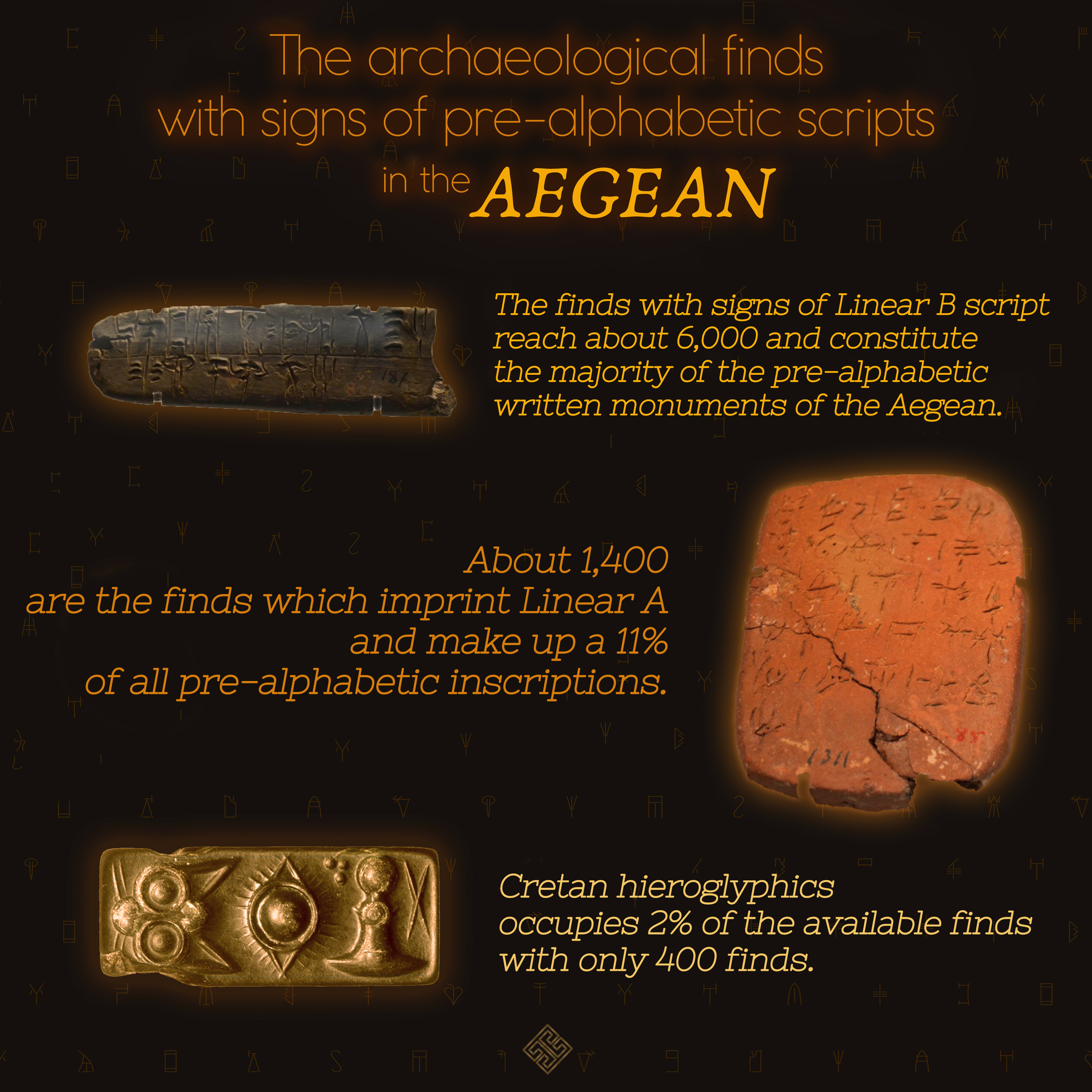

Over the last decades, a great deal has been written about the causes and origin of the migratory movement of these ethnic groups from the Aegean and Asia Minor, but even today there are many unanswered questions .

These peoples had not only dismantled the once mighty Hittite Empire, but in their advance they had razed Arzawa, Alalakh, Karkemish, Ugarit, Alashia, Tarsus, and Amurru.

In Egypt, we know that some of these groups – such as the Denen, Lukka, and Sherden – had already appeared during Akhenaten’s reign (1352-1336 BC), and members of the Lukka and Sherden are listed as mercenaries fighting on the side of Ramses II in the famous Battle of Kadesh (1274 BC) against the Hittite empire.

Given the notable historical and archaeological uncertainties surrounding this episode, we can only narrate the succession of events presented by Ramses III.

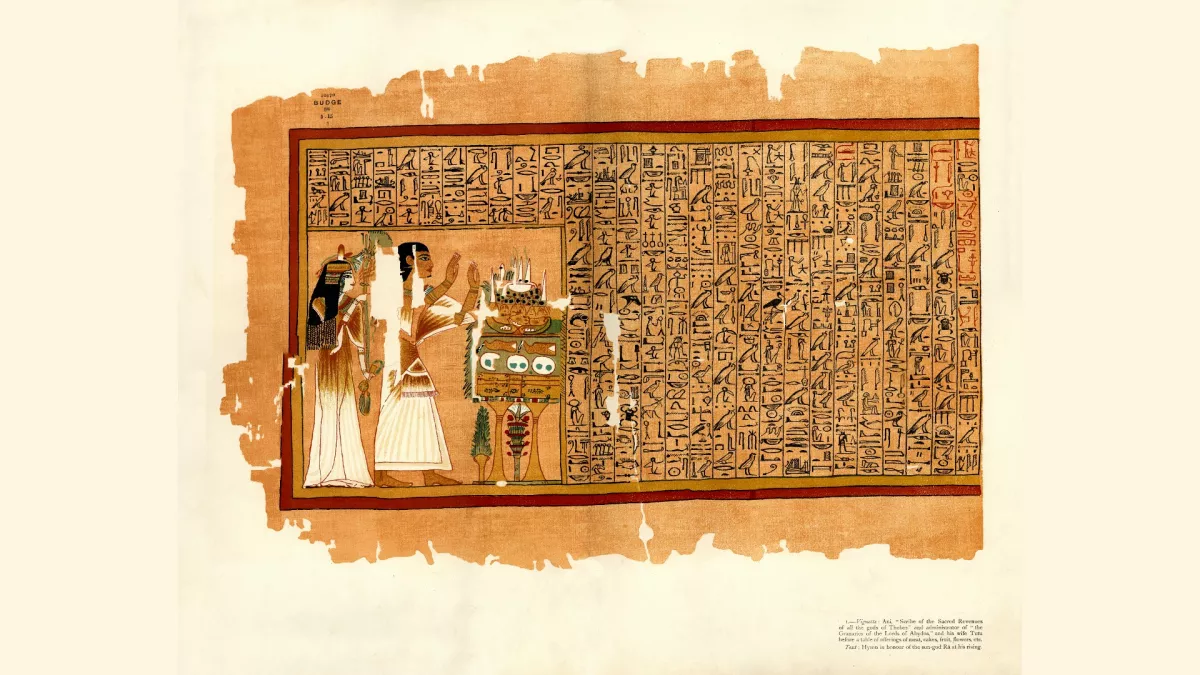

This scene from the north wall of Medinet Habu is often used to illustrate the Egyptian campaign against the Sea Peoples in what has come to be known as the Battle of the Delta.

Ramses III against the Sea Peoples

Around 1177 BC, the Danauna, Shakalash, Uashasha, Alasa, and Chekker completely encircled Egypt, heading toward it by sea and land, and both East and West.

To face them, Ramses III prepared a war fleet and raised a large army of infantry in arms. Curiously, there was no shortage of mercenaries among the Pharaoh’s forces from the ranks of the Sea Peoples, as had happened in the past.

Judging by the scenes contained in the Medinet Habu reliefs, the war was decided in two major battles, first a land one and then a naval one.

Archeology has not found any evidence that indicates the exact place of these clashes, but we can assume that, if they occurred as indicated, they were at two points close to each other and as far as possible from the Nile valley.

Based on this, it is believed that the land battle could have taken place at some point between the eastern border of the Delta and the southern coast of the Palestinian strip, while the naval combat occurred when an enemy fleet penetrated precisely in the Nile Delta.

It should also be noted that in both encounters the pharaoh would have intervened, although in a different way:

In the land battle he would intervene directly, but in the naval he would support his navy from the coast. On land, Pharaoh’s forces had time to prepare, so they would have mercilessly ambushed the migrant caravan heading towards Egypt.

Despite this overwhelming victory, this enemy could not be defeated so quickly because it was not a political entity and therefore did not act as a coherent group.

In this way, other groups continued to be a threat to Egyptian stability that had to be alleviated.

On this occasion, the scenes in Medinet Habu show us a group of foreign ships that entered a waterway with the clear intention of landing their warriors on the shore.

However, they were unaware that they were being watched and, before the maneuver came to an end, the Egyptian navy would have suddenly emerged to attack them by surprise.

At the same time, from the ground the infantry would finish off those who had managed to disembark and the enemy ships carried towards the coast would be attacked by the Egyptian archers.