How and when did the first populations move into North Africa? What is the significance of the detected "Aegean/Greek DNA"? How did the Carthaginians maintain their cultural dominance? (9-minute read)

Carthage was founded in the late 9th century BCE (traditionally 814 BCE) as a colony of Tyre, at a time when Tyre was a thriving commercial center. Therefore, the first inhabitants were Phoenician settlers — Semitic populations from the Levantine coasts, descendants of the ancient Canaanites. However, from the very foundation of the city, it is likely that local Berber (Libyan) populations of North Africa coexisted in the area, with whom the Phoenician settlers interacted and possibly intermarried. The very name of the city (Qart-Ḥadašt, meaning "New City") denotes a new settlement in foreign territory, but its development was closely tied to the local environment. Archaeological and historical evidence suggests that Carthage quickly evolved from a small trading post into a prosperous city-state with its own "Carthaginian" civilization. This civilization was clearly Phoenician (Semitic language, religion, customs), but the ancestry of the city's population was not purely Phoenician.

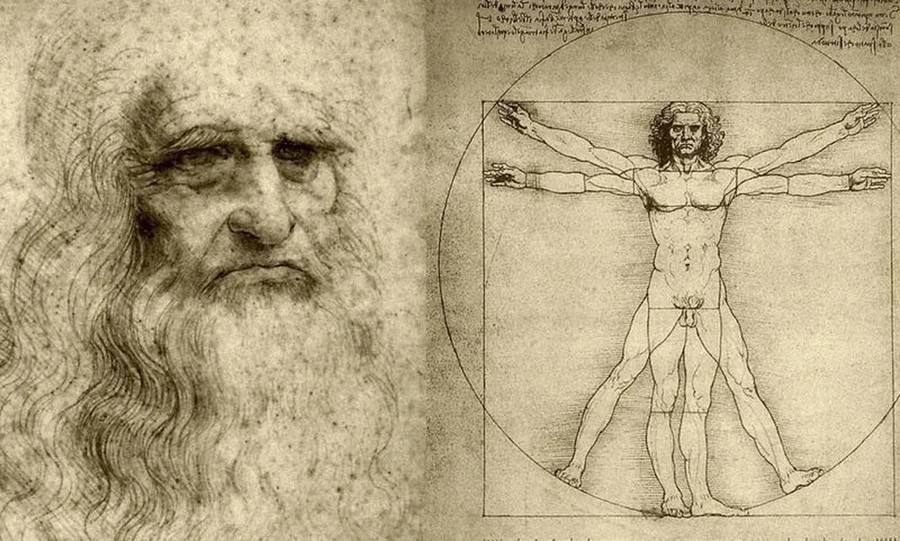

A recent paleogenetic study shed the first light on the biological composition of the early Carthaginians. The so-called "Young Man of Byrsa"—a man from the late 6th century BCE discovered in a burial chamber at Byrsa Hill in Carthage—revealed through ancient DNA analysis a maternal lineage (mitochondrial haplogroup U5b2c1) that is rare and European, originating from prehistoric populations in the northern Mediterranean. Specifically, this mtDNA links the individual's ancestry to regions such as the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, or the northern Mediterranean coasts. The discovery constitutes the first direct evidence suggesting that even the early inhabitants of Carthage could have mixed ancestry, including European elements. In other words, the presence of such an ancient European genetic marker (U5b2c1) in North Africa indicates that Phoenician settlers had incorporated individuals from earlier Mediterranean populations (e.g., from Sicily, Sardinia, or Iberia) into their communities. This initial genetic diversity aligns with the historical image of a port city open to various ethnic groups. Although Carthage may have been founded by a few dozen or hundreds of Phoenician settlers, within a few generations its population expanded through admixture with local and other northern Mediterranean peoples. Truthfully, we have long understood that the Phoenicians' cultural dominance in Carthage did not imply absolute demographic dominance. Many ancient Greek colonies also observed the same phenomenon.

This reality became even clearer in a recent large-scale study of 103 ancient genomes from Carthage itself and other Phoenician/Carthaginian sites. Researchers identified a recognizable "Carthaginian" genetic profile, but it bore minimal relation to the populations of ancient Phoenicia. Instead, it was primarily composed of European (Greek/Aegean and Sicilian) and North African genotypes.

The First Neolithic Expansions—Prehistoric Population Flows into North Africa

To understand how European genetic elements appeared in North Africa long before Carthage's founding, we must examine population movements during the Neolithic period. The transition from hunter-gatherer economies to farming and animal husbandry occurred in North Africa approximately 7,500 years ago. Two main theories exist: either that local Mesolithic populations gradually adopted Neolithic innovations or that incoming farmers migrated into the area, bringing their way of life. Ancient DNA now clarifies this process. Furthermore, recent genome studies of prehistoric skeletons in the Maghreb revealed clear ancestry shifts during the Neolithic transition: the earliest Neolithic burials in Northwest Africa primarily show European Neolithic ancestry. The evidence implies that the initial farmers who emerged in Morocco and Algeria were predominantly descended from Neolithic populations from southern Europe. Researchers conclude that migrant European farmers introduced agriculture to Northwest Africa, which then rapidly disseminated among local groups.

This pattern fits into the broader wave of Neolithic farmer expansions from the Near East into Greece and Europe. It is well known that early farmers began in Anatolia and the Levant, spreading gradually westward via coastal Mediterranean routes to the Balkans, the Italian Peninsula, Sicily, Sardinia, and Iberia. Archaeologically, the spread of Impressa/Cardial pottery along coastal zones reflects the so-called "Mediterranean route" of Neolithic expansion. Notably, the appearance of agriculture in northeast Africa (e.g., the eastern Rif in Morocco) is nearly synchronous with its emergence in southern Spain, around 5500 BCE, suggesting maritime transfer of people and ideas. Thus, the wider agricultural dissemination led to a significant expansion of Neolithic populations from Europe into North Africa.

Note that a single migratory stream did not limit the genetic history of North Africa during the Neolithic. In addition to the European Neolithic influx, later contributions from the Near East are detectable. During the Middle Neolithic period, around 5000 BCE, the Maghreb genetic profile shows the introduction of a Levantine element, coinciding with the arrival of pastoralism (cattle, sheep, goats) in the region. This finding suggests that groups of herders possibly migrated westward from the eastern Mediterranean or the Nile Valley, bringing new genetic influences. Ultimately, by the end of the Neolithic, populations of the Maghreb exhibited a mixed genetic profile, combining local Paleolithic/Mesolithic heritage, European Neolithic farmer ancestry, and Near Eastern admixture. This prolonged prehistoric admixture explains why certain ancient European haplogroups (such as U5) or "Sardinian-type" genetic elements later appear among North African populations.

Regarding specifically Mycenaean, Sicilian, or Sardinian populations and their connection to North Africa, the data are fragmentary but indicative. There is no documented direct mass migration of Mycenaeans into North Africa during the Bronze Age. However, the presence of Mycenaean artifacts in Egypt and possible contacts with Libya suggest some level of interaction. After the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization (~1200 BCE), groups from the Aegean participated in the so-called "Sea Peoples," who reached as far as Egypt. Among them were the Sherden (possibly from Sardinia) and the Shekelesh (perhaps from Sicily). Although these groups clashed with Egypt, some may have settled in Libya or Canaan. These late-Chalcolithic or early Iron Age movements may have had a limited impact on western North Africa, though a minor genetic contribution from Aegean/European Bronze Age populations cannot be ruled out.

Moreover, the genetic landscape of the Carthaginians later exhibits strong affinities with ancient Greek populations, possibly linked to these early European movements or to Greek colonies established in Africa.

As for Sicily and Sardinia, these two major Mediterranean islands acted as bridges for population movements. Especially Sicily, due to its proximity to the Tunisian coast, served as a natural channel: early Neolithic settlers could have crossed in either direction between Tunisia and Sicily. During the 3rd millennium BCE (the Bronze Age), Sicily received influences from the Aegean world (e.g., Mycenaean finds) and later from Phoenician and Greek settlers. Sardinia, on the other hand, remained relatively genetically isolated for millennia (modern Sardinians preserve a high proportion of ancient Neolithic ancestry). Nonetheless, the Sherden people's history suggests some early contact with the eastern Mediterranean. In historic times, Carthaginian expansion led to the establishment of Phoenician colonies in Sardinia (e.g., Tharros), prompting some local population movements. Overall, we can say that the genetic impact of Sicilian and Sardinian populations on North Africa is detectable indirectly: either through early Neolithic dissemination (European farmers reaching the Maghreb) or through later historical interactions (e.g., integration of Sicilians into the Carthaginian network).

Phoenician Expansion and Genetic Interactions in the Western Mediterranean

During the Iron Age (1st millennium BCE), the Phoenicians expanded their maritime trading network, establishing numerous outposts and colonies throughout the western Mediterranean. By the 11th–10th century BCE, Phoenician settlements appeared in Spain (e.g., Cádiz), the Balearic Islands, Sicily, Malta, Sardinia, and beyond. The genetic contribution of these Semitic settlers to local populations had long been an open question. Traditionally, it was believed that the "Punic" populations (i.e., the western Phoenician colonies such as Carthage) would exhibit a strong Phoenician (Levantine) genetic signature. However, large-scale ancient DNA analyses have overturned this assumption. Researchers discovered that populations in the western Mediterranean received limited direct genetic input from Phoenician mother cities (Tyre, Sidon, etc.).

Despite their intense cultural, economic, and linguistic influence, the original Phoenician cities contributed minimal direct DNA to the Punic populations of the central and western Mediterranean. The spread of Phoenician culture thus occurred not through mass migration but primarily through the diffusion of cultural models and the integration of local communities.

Specifically, every Phoenician-Carthaginian site studied shows remarkable heterogeneity regarding its inhabitants' origins. Researchers detected an "extremely heterogeneous" genetic profile in ancient skeletons from these sites. In almost all Punic communities — from Carthage itself to colonies in Iberia, Sicily, Sardinia, and North Africa — the majority of individuals exhibited ancestries similar to those of ancient Sicilian and Aegean populations (southern Europe), while a significant portion had North African ancestry. In contrast, direct Near Eastern/Semitic genetic input was minimal. This practically means that in Phoenician colonies, people of diverse backgrounds lived together: individuals of local North African descent alongside others of predominantly European (Sicilian/Greek) origin. The different Punic communities were connected via maritime "kinship networks." For instance, a pair of distant relatives (approximately second cousins) were found: one buried in a Phoenician city in North Africa, the other in a Phoenician settlement in Sicily. Such findings illustrate the cosmopolitan character of the Carthaginian network, where movement and intermarriage across different regions were common.

This theory also explains how Phoenician settlers, initially a demographic minority, eventually genetically assimilated local populations rather than replacing them. As geneticist Pierre Zalloua aptly put it, "The Phoenicians were a civilization of integration and assimilation — they settled wherever they traveled." Despite their broad and diverse biological ancestry, these mixed populations transmitted their cultural identity (language, religion, and technical knowledge).

The case of Carthage shows that a group can be very influential in trade and culture even if they are not the largest population, similar to some theories about how Indo-European languages spread, but the history, society, and population of northern Africa at that time were quite different.

In summary, the Carthaginian rulers spoke the Phoenician language and worshipped Phoenician gods, but their subjects and allies came from various Mediterranean nations. In the end, the genetic background of the Carthaginians in the western Mediterranean is spread out and varied, showing a blend of European and African genes with some small Semitic influences, instead of a clear "Phoenician" genetic identity. This conclusion aligns perfectly with historical accounts of the multiethnic societies of the western Mediterranean and highlights how population movements are inextricably linked to cultural interactions.