Over the last two decades, evidence of a high-status early medieval settlement has been uncovered just four miles from Sutton Hoo. This emerging picture raises an important question: what can Rendlesham reveal about how royal power developed and functioned in early medieval England?

Today, Rendlesham is a quiet rural village near Woodbridge in southeast Suffolk, but its early medieval past has long been a topic of curiosity. The site appears briefly in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, where it is described as a vicus regius a royal settlement. Like Yeavering, the Northumbrian royal center located about 250 miles (400km) to the north, Rendlesham is portrayed as a site of royally sanctioned baptisms during the 7th century. Interest in its significance grew even further after the discovery of the Sutton Hoo princely burials in 1939, only a short distance away.

Despite its reputation, Rendlesham’s royal residence remained difficult to pinpoint. Several different locations within the parish were proposed, but none could be confirmed. Fieldwalking in the 1980s revealed large amounts of 5th- to 9th-century pottery in fields north and west of the parish church of St Gregory, showing that people lived there during that time. However, the material did not clearly indicate a settlement of the high status described by Bede.

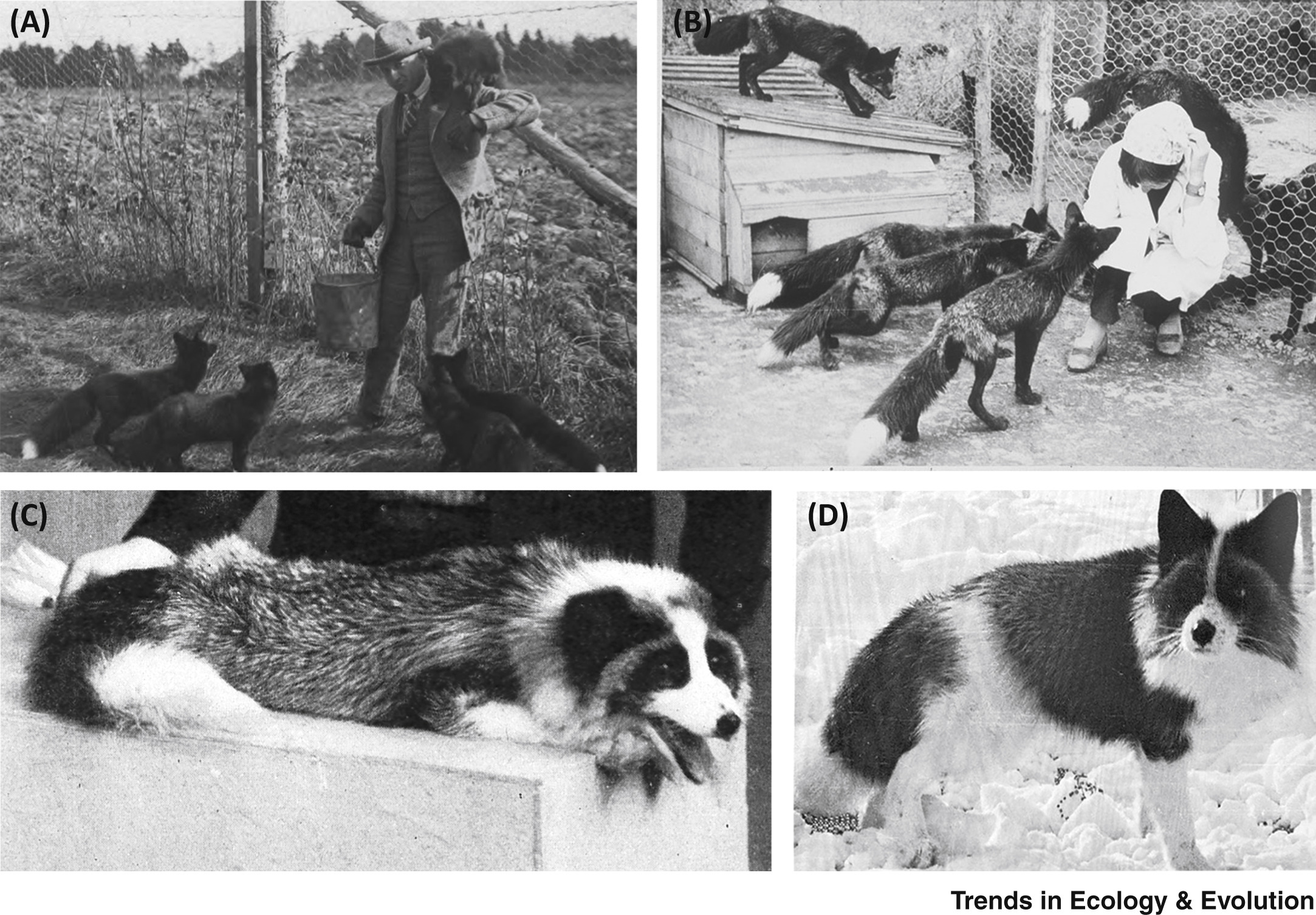

High-quality metalwork from Rendlesham, including gold-and-garnet jewellery, indicates an elite settlement: the site of the vicus regius described by Bede. Scale: 3:1

Over the past two decades, the understanding of Rendlesham has changed dramatically, thanks to a series of linked archaeological projects that have gradually uncovered clues from the Suffolk landscape, bringing this long-lost community back into sharp focus. While individual discoveries were previously reported in journals, the team has now synthesized their wider interpretations in a comprehensive monograph, accompanied by a paper in Medieval Archaeology summarizing three years of excavation (both are open access online). These findings reveal new insights not only into elite early medieval activity in the Deben river valley but also into broader landscapes of power that appear to have been more organised, interconnected, and enduring than previously understood.

This research traces the rise and decline of Rendlesham as a major power center, situates it within its wider context, and deepens understanding of the early East Anglian kingdom.

Searching for a Settlement

The modern story of Rendlesham’s rediscovery began in 2007, when the owner of nearby Naunton Hall reported illegal metal-detecting on his land. In response, Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service organised a controlled survey with four trusted detectorists who had prior experience with the council and commercial excavations.

The survey uncovered coins and other metal artifacts dating from the 5th to 8th centuries, many indicating high-status activity. In light of these finds and ongoing illegal metal-detecting the pilot study was expanded. Between 2008 and 2014, the detectorists systematically surveyed the entire estate, covering approximately 170 hectares (420 acres). Combined with geophysical surveys and detailed analysis of aerial photographs, this work provided critical clues about the nature, location, and extent of the settlement.

Project volunteers excavating the possible ‘cult house’ within Trench 16 in 2023

Of the roughly 5,000 artifacts recovered from the plough soil during these investigations, about 27% date to the early medieval period. By comparison, early medieval finds account for only 5% of all discoveries recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme across Suffolk. This striking concentration at Rendlesham points to a major center of activity in the area but where exactly was the settlement?

Each metal-detected object was carefully logged using GPS, allowing researchers to map the distribution and density of the artifact scatter. Geophysical surveys over the densest concentrations revealed a complex array of subsurface features. Trial-trenching in 2013 showed that some of these were Grubenhäuser, the characteristic sunken-featured structures associated with early medieval settlements.

Until this stage, the project had been relatively modest, consisting of a series of small initiatives that worked around the agricultural calendar and successive funding rounds. A major expansion came in 2017, when a Leverhulme Trust grant funded expert analysis of the vast dataset of metal-detected finds. This support launched a 3.5-year multidisciplinary project based at University College London’s Institute of Archaeology, the University of East Anglia, and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

In parallel, a National Lottery Heritage Fund grant supported Rendlesham Revealed, a community archaeology initiative led by Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service. Bringing together local groups, the project carried out three summer excavations between 2021 and 2023, targeting key features identified in earlier geophysical surveys.

Together, these complementary strands of research have built a detailed picture of both elite and everyday life in 5th- to 8th-century East Anglia, offering insights into the largest and richest settlement of its type yet discovered in England.

Combined results of magnetometer surveys in 2008-2014.