Panel 3 of the Ketton Mosaic depicts King Priam of Troy weighing gold vessels to match the weight of his son Hector, a story drawn from the lost Greek play Phrygians by Aeschylus. Archaeologists were able to reconstruct the burned section of the mosaic by carefully tracing the outline of the tiles.

Recent research has confirmed that the Ketton mosaic in Rutland—one of the most significant Roman-era discoveries in Britain in the past century—does not illustrate scenes from Homer’s Iliad, as was previously thought. Instead, it reflects an alternative, long-lost version of the Trojan War narrative popularized by Aeschylus.

The mosaic incorporates artistic patterns and motifs that had circulated across the Mediterranean for centuries, indicating that Roman-British craftsmen were more closely connected to the wider classical world than previously assumed.

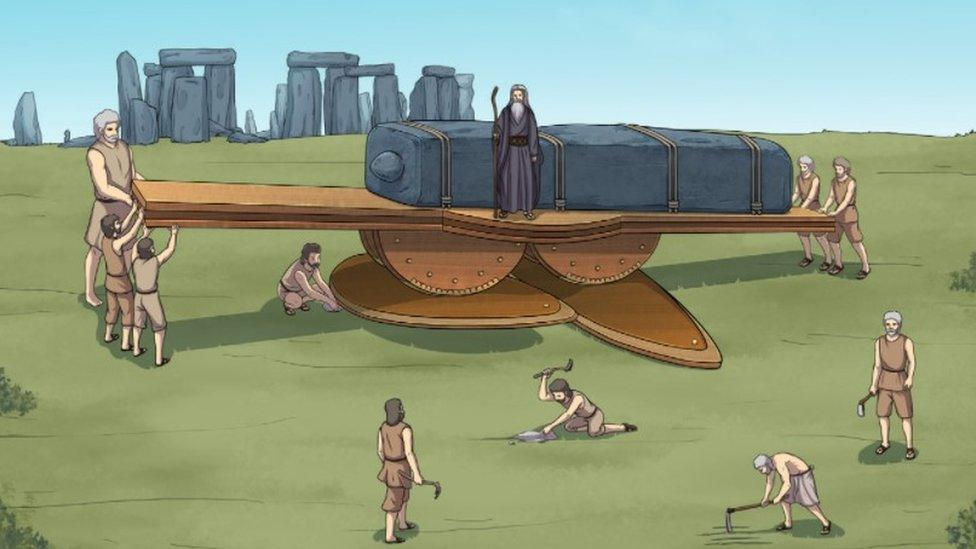

Discovered in 2020 during the COVID-19 lockdown by a local resident, the mosaic prompted a major excavation by the University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS), funded by Historic England. The mosaic and its surrounding villa have since been designated a Scheduled Monument due to their national significance. Collaborative excavations by Historic England and ULAS in 2021 and 2022 are being compiled for publication.

The Ketton mosaic features three dramatic scenes involving Achilles and Hector: their duel, the dragging of Hector’s body, and its eventual ransom by King Priam, in which Hector’s body is weighed against gold.

A first-century silver jug from Roman Gaul already featured the same design seen in Panel 1 of the Ketton Mosaic. On the left, Achilles sits beside his shield, surrounded by his guards. In the center, Hector’s body is displayed on a massive set of scales, with a human face forming the focal point. On the right, King Priam, wearing his distinctive hat and robe, loads the scales with gold vessels while his bodyguards look on. (This scene is comparable to a nineteenth-century line drawing of the Berthouville Treasure, now held at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.)

The Trojan War—most famously recounted in Homer’s Iliad—was a legendary ten-year campaign waged by Greek forces against Troy, ruled by King Priam, to reclaim Helen of Sparta.

Recent analysis shows that the Ketton mosaic is not based on Homer’s epic, as initially thought, but instead reflects a lesser-known tragedy, Phrygians, by the Athenian playwright Aeschylus. While the Romans were familiar with multiple retellings of the Trojan War, the villa owner at Ketton would have gained prestige by displaying one of the rarer, more niche versions.

The research also highlights that the mosaic’s design skillfully integrates artistic patterns that had been used by craftsmen across the ancient Mediterranean for centuries, demonstrating the connection of Roman Britain to the wider classical world.

Panel 2 of the Ketton Mosaic depicts Achilles dragging Hector’s body behind his chariot while Hector’s father, Priam, pleads for mercy. A Greek vase from ancient Athens, created some 800 years earlier, shows the same composition: the waving figure, the shield, the chariot group, the running figure with outstretched arms, and even the snake coiled beneath the horses all follow the same visual schema.

The Ketton Mosaic not only depicts scenes from Aeschylus’ version of the Trojan War, but the top panel is based on a design from a Greek vase dating to the time of Aeschylus, roughly 800 years before the mosaic was created. Analysis shows that other panels also draw on patterns found in older silverware, coins, and pottery from Greece, Turkey, and Gaul. This demonstrates that Romano-British craftsmen were not isolated, but participated in a broader Mediterranean network, passing artistic motifs and pattern catalogues down through generations. The mosaic combines Roman-British craftsmanship with a heritage of Mediterranean design.

The discovery of the mosaic in 2020 has revealed a previously underappreciated level of cultural integration across the Roman world, suggesting that Roman Britain may have been far more cosmopolitan than often assumed. The research offers a nuanced view of the influences and interests of the villa’s occupants and, more broadly, of people living in Roman Britain at the time.

The study also highlights how stories of Greek heroes like Achilles and Hector were transmitted not only through texts but through a rich repertoire of visual motifs, created across a variety of media, from pottery and silverware to paintings and mosaics.

A section of Panel 1 of the Ketton Mosaic depicts Hector, the Trojan prince, in his chariot. An earlier example of the same design appears on a second-century Roman coin from Ilium in Turkey, which is also labeled “Hector.”