Minoan Engineers Built Secret Wall to Protect Palace from Landslides

During the 2025 excavation season at the Palace of Archanes—one of Crete’s most intriguing Minoan sites—archaeologists made a surprising discovery. A peculiar, slanted wall in the palace’s central courtyard, long considered a mere architectural curiosity, was revealed to be part of a sophisticated protective system designed to shield the complex from potentially devastating landslides.

The Greek Ministry of Culture announced the find, highlighting the advanced engineering skills of the Minoans during the Middle Bronze Age. The discovery shows that Archanes’ architects achieved a level of planning and technical expertise comparable to the renowned palaces of Knossos and Phaistos.

A Wall That Defied Explanation for Decades

For years, researchers were puzzled by the skewed, inward-leaning wall. Made from unshaped, irregular stones and seemingly closing off a section of the courtyard, it appeared crude and inconsistent with the refined Minoan architectural style. Scholars debated its purpose: Was it a later addition, a makeshift barrier, or a failed experiment?

The 2025 excavation finally answered these questions. Geological analysis showed that the palace sits beneath a steep rock face prone to rockfalls. The slanted inner wall was a concealed retaining structure designed to absorb impacts and stabilize the slope above.

Engineering Meets Aesthetics

Although the inner wall served a critical structural function, its rough appearance did not align with Minoan standards of beauty. To maintain the visual harmony of the courtyard, architects built a second, outer wall using carefully carved porous stone blocks. This elegant outer layer matched the palace’s architectural style, concealing the inner wall while allowing it to perform its protective role silently.

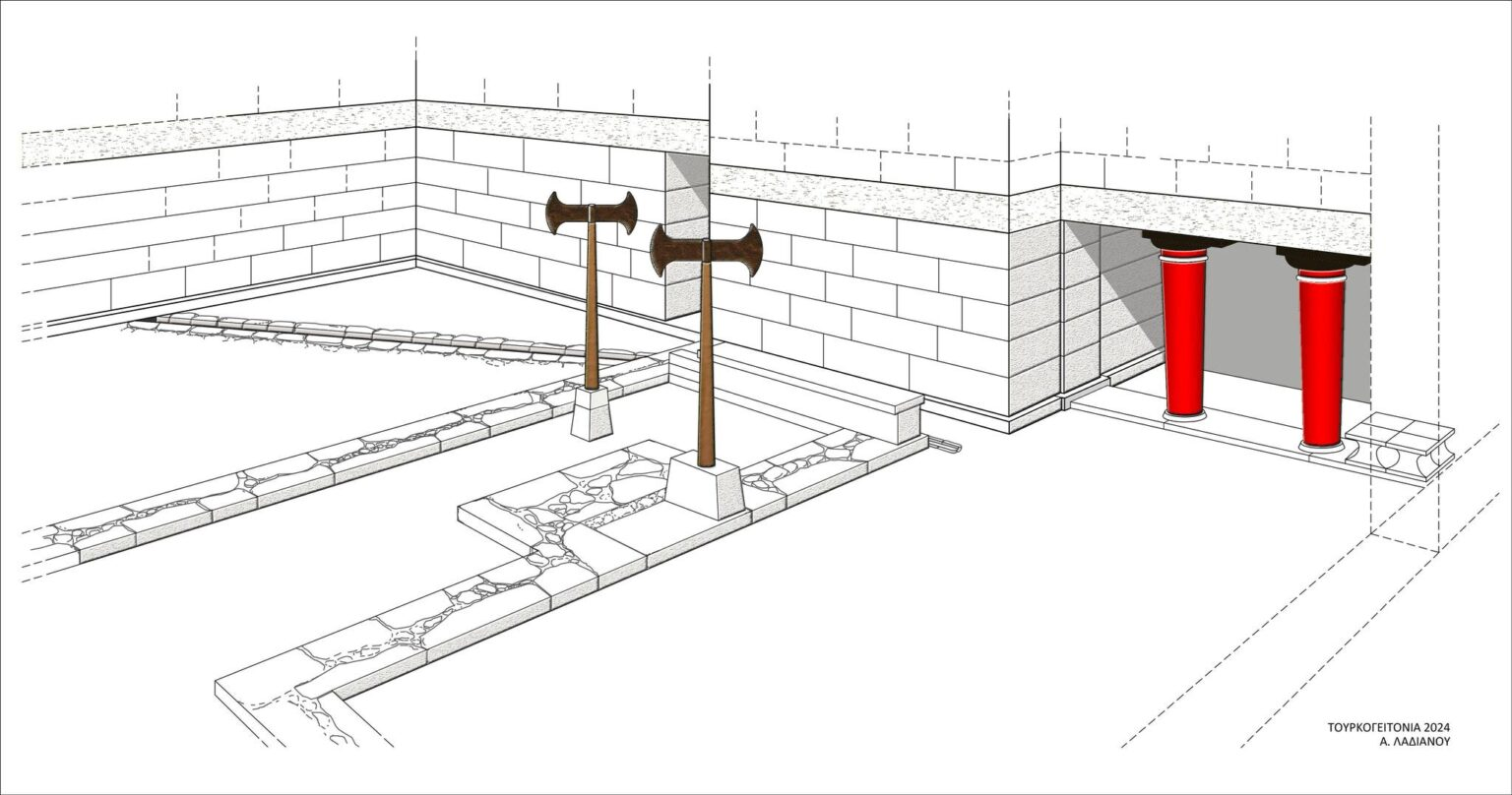

Reconstruction of the Sacred Gate in the palace of Archanes.

New Insights into a Long-Occupied Ritual and Administrative Center

Excavations along the upper levels of the double wall uncovered layers containing abundant Mycenaean pottery, including kylikes, as well as traces of later activity. These discoveries confirm that Archanes remained in use long after the palace’s final destruction around 1450 BC. The site’s enduring occupation is well documented: it was first damaged by an earthquake around 1700 BC, subsequently rebuilt, and continued to flourish until the mid-15th century. Afterward, Mycenaean and later occupants continued to utilize the area.

In the southeastern part of the excavation, archaeologists revealed a new passage connecting the Central Courtyard to the palace’s easternmost rooms. This space is divided by stone slabs, including one large trapezoidal block that once held a parapet later destroyed by a Mycenaean wall.

A Rare Ritual Find

The most remarkable object discovered is a naturally shaped stone exhibiting subtle anthropomorphic features. Found on a floor where it had fallen from an upper level, the stone likely belonged to a cultic installation. Researchers suggest it formed part of a “fetish shrine,” a ritual corner similar to those found at Knossos. Such shrines, featuring natural stones considered animate or divine, provide rare insight into the intimate religious practices of Minoan households and palaces.

The easternmost part of the excavation and the central entrance of the palace with the quadruple amphikylon altar.

Reconstructing the Palace’s Elite Quarters

Recent research from the 2023–2025 campaigns reveals that the northern sector of the Palace of Archanes once housed a luxurious, multi-story elite wing. Excavations uncovered a complex network of interconnected rooms, adorned with fresco fragments, gypsum door jambs, and mortar-coated walls. Floors made of schist slabs still display their characteristic Minoan decorative borders—raised mortar strips framing each slab—a feature found across Crete but exceptionally well preserved at Archanes.

These findings suggest that the palace was designed not only for administrative and ceremonial purposes but also as a high-status residence. Architectural sequencing confirms a three-story structure, supporting the view that Archanes served as a secondary palace closely linked to Knossos.

A Palace Hidden in Plain Sight

Archanes holds a unique place in Minoan archaeology. The palace lies beneath the modern town, specifically in the Tourkogeitonia district, making excavation challenging and often fragmentary. Early in the 20th century, Sir Arthur Evans identified signs of monumental Minoan structures here, noting wall surfaces and a large circular aqueduct. He also attributed nearby elite grave goods, now in the Ashmolean Museum, to this area.

It was only through detailed surveys examining the basements of modern houses and mapping surviving walls that the palace’s core was accurately located. This work showed that earlier researchers had been searching in the wrong place for Evans’s so-called “summer palace.” What they discovered instead was far more significant: a major Minoan palatial center featuring architectural innovations not seen elsewhere on Crete.

Clay head of a female figure with traces of red pigment.

Engineering, Ritual, and Resilience

The recently uncovered landslide-protection system adds a new dimension to the story of Archanes. It shows that Minoan architects not only constructed monumental buildings but also incorporated advanced strategies to manage geological risks. At Archanes, functional engineering and aesthetic ideals coexisted perfectly hidden inner walls absorbed destructive forces, while the visible façades preserved the palace’s elegant appearance.

As the 2025 excavation season comes to a close, the Palace of Archanes stands out as a site where ritual practice, elite living, and innovative engineering intersect. The slanted double wall, once considered an oddity, is now recognized as a remarkable example of Minoan ingenuity a quiet reminder that behind the civilization’s celebrated artistry lay a sophisticated understanding of the natural world and the architectural skill to master it.