On the windswept hills overlooking Turkey's vast southeastern plains, new archaeological discoveries are revealing how life might have looked 11,000 years ago when the world's earliest communities began to emerge.

The archaeological site of Karahan Tepe in southeastern Turkey is shedding new light on our understanding of the earliest human settlements.

Neolithic Insights from Karahan Tepe Excavations

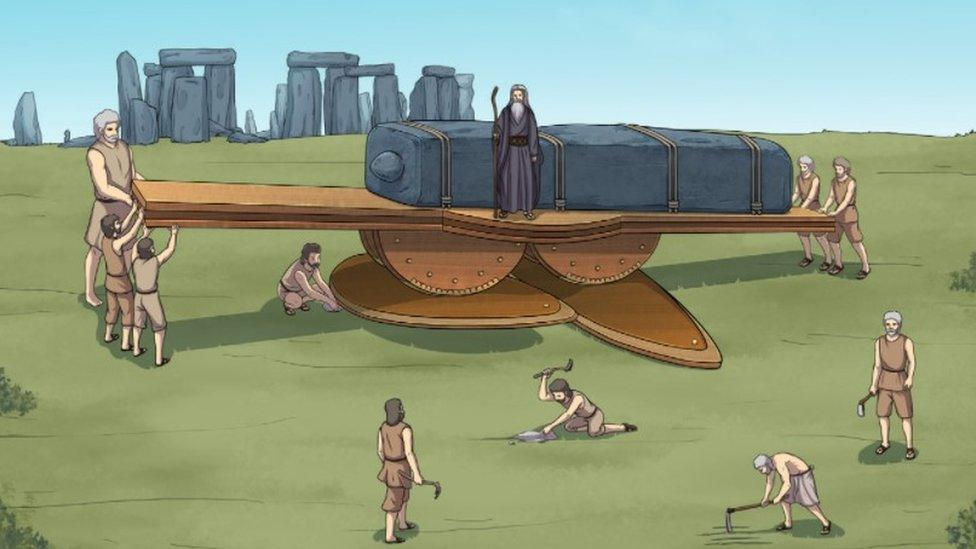

Recent discoveries at Karahan Tepe include a stone figurine with stitched lips, carved stone faces, and a black serpentinite bead featuring expressive faces on both sides. These artifacts provide new clues about Neolithic beliefs and rituals.

“The growing number of human sculptures reflects the shift toward settled life,” said Necmi Karul, the lead archaeologist at Karahan Tepe. “As communities became more sedentary, people gradually distanced themselves from nature, placing the human figure and human experience at the center of their worldview.” He highlighted a human face carved onto a T-shaped pillar as a key example.

The excavation is part of Turkey’s government-backed “Stone Hills” project, launched in 2020 across 12 sites in Şanlıurfa province. Culture Minister Nuri Ersoy has described the region as “the world’s Neolithic capital.”

The project also includes the UNESCO World Heritage site Göbekli Tepe—known as “Potbelly Hill” in Turkish—which contains the oldest known megalithic structures in Upper Mesopotamia. Excavations at Göbekli Tepe were first initiated by the late German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt in 1995.

Lee Clare of the German Archaeology Institute, commenting on some of the new finds displayed at Karahan Tepe’s visitor centre, said the discoveries challenge long-held assumptions about humanity’s transition from nomadic hunter-gatherers to early settlements. “Every building we study offers a glimpse into someone’s life. Each layer we excavate brings us closer to understanding an individual—we can almost connect with them through their remains. These finds provide insights into their belief systems,” he explained.

A pillar and a human statue are among the artifacts offering clues about Neolithic life.

Understanding Prehistoric Life at Karahan Tepe

Over the past five years, excavations at Karahan Tepe and other sites have produced “a remarkable amount of data,” according to archaeologists involved in the project.

However, fully understanding these prehistoric societies remains challenging. “We don’t have any written records, obviously, because it’s prehistory,” said Lee Clare, who has worked at Göbekli Tepe since 2013.

Identifying the individuals represented by statues or figurines is likely impossible, given they date to “a period before writing, around 10,000 years ago,” explained Necmi Karul, who also leads the dig at Göbekli Tepe and coordinates the Stone Hills project. Nevertheless, as the number of discoveries grows and archaeologists learn more about the contexts in which they appear, it becomes possible to perform statistical analyses and make meaningful comparisons.

The settlements began emerging after the last Ice Age, Karul added. “The changing environment created fertile conditions, allowing people to feed themselves without constantly hunting. This, in turn, supported population growth and encouraged the development and expansion of permanent settlements in the area,” he said, pointing to the early signs of a highly organized society.

Once communities started producing surpluses, there was wealth and poverty a 'slippery slope' leading toward the modern world, says Lee Clare of the German Archaeology Institute.

Emerging Social Structures in Neolithic Communities

As settlements became more permanent, new social dynamics began to take shape, explained Lee Clare. “Once people produced a surplus, distinctions between rich and poor appeared,” he said, highlighting early signs of social hierarchy. “What we are seeing here marks the beginning of that process. In many ways, it’s a step along the path toward the modern world.”

The ongoing excavations are reshaping our understanding of the Neolithic period, with each site contributing uniquely to the scientific record. Emre Guldogan of Istanbul University, lead archaeologist at the nearby Sefer Tepe site, noted that Karahan Tepe and the broader Stone Hills project reveal “a highly organized society with its own symbolic world and belief systems,” challenging older notions of a “primitive” Neolithic era.

“These communities shared certain traits, yet they also developed distinct cultural differences,” Guldogan added, emphasizing the complexity and diversity of early settled life.

Archaeologists say they are seeking to better understand the finds, which date to a period before writing, around 10,000 years ago.

Human and Animal Symbolism Across the Stone Hills

At Karahan Tepe, human symbolism is prominent, whereas at Göbekli Tepe, animal imagery dominates. Archaeologists suggest that these differences reflect how each community chose to represent their living environments.

“Every new discovery raises fresh questions about the people behind these creations,” said Emre Guldogan.

The recent finds have also increased the region’s appeal beyond its traditional religious significance. Previously known mainly as the area where Abraham is believed to have settled a figure revered in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam the Stone Hills sites now attract a broader spectrum of visitors.

“Before excavations began at Karahan Tepe and other sites, the area mainly drew religious tour groups,” explained tourist guide Yakup Bedlek. “Now, with the emergence of new archaeological zones, a more diverse mix of tourists is visiting the region.”