A new study suggests that people living in Italy during the Iron Age began adopting a more varied diet between the 7th and 6th centuries BC, based on detailed analysis of ancient human teeth.

Reconstructing the lifestyles of ancient populations is difficult, as it depends on rare, well-preserved human remains. Teeth, however, are especially valuable to researchers because they act as long-term records of an individual’s life, particularly diet and health. Even so, comparing dental evidence across different historical periods remains challenging.

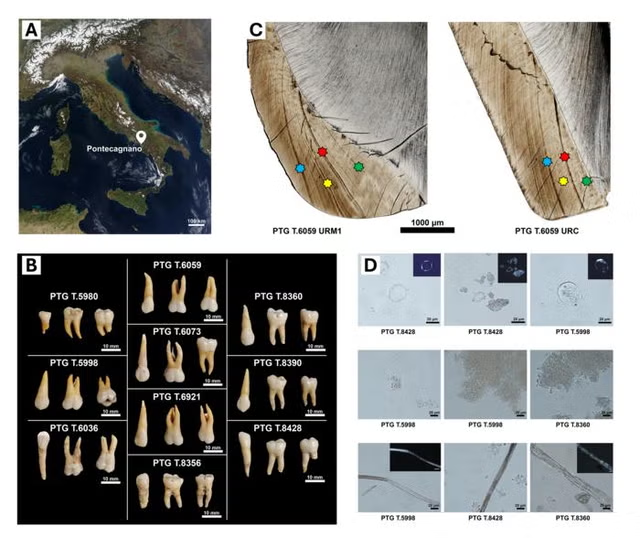

In this study, researchers analyzed teeth recovered from the archaeological site of Pontocagnano in Italy to better understand the diet and health of individuals living in the region during the Iron Age. The team examined dental tissue from 30 teeth belonging to 10 individuals, focusing on canines and molars to trace each person’s early life history, particularly during their first six years.

The analysis revealed that Iron Age Italians consumed a diet rich in cereals, legumes, and carbohydrates, and regularly included fermented foods and drinks. According to Roberto Germano, one of the study’s authors, the findings allowed researchers to closely track childhood growth and health while identifying dietary markers that show how the community adapted to environmental and social pressures.

Emanuela Cristiani, another author of the study published in PLOS, explained that dental calculus contained starch granules from cereals and legumes, yeast spores, and plant fibres. These remains provide direct evidence of everyday eating habits and certain daily activities within the community.

The results strongly indicate that fermented foods and beverages were a regular part of the diet. Researchers suggest this dietary diversification may be linked to increased contact with other Mediterranean cultures during the period.

The study also identified signs of physiological stress in the teeth at around one and four years of age, which may reflect periods when young children were particularly vulnerable to illness or environmental hardship.

Although the sample size is limited and may not represent all Iron Age populations in Italy, the findings offer a detailed and tangible insight into diet and daily life in the region. Alessia Nava of Sapienza University of Rome noted that studies like this demonstrate how modern scientific techniques are transforming understanding of the biological and cultural adaptations of ancient societies.