The remarkable find was voted 'find of the year' by Norwegian archaeologists.

Antlers bearing cut marks were the archaeologists' most important clues to what the facility was used for.

During the autumn, archaeologists from the University Museum of Bergen have been excavating a 1,500-year-old reindeer mass-trapping site on Aurland Mountain.

Until now, the existence of this complex trapping system had been unknown. More details about the discovery can be found here.

On November 15, the find was honored as “Find of the Year” at the Norwegian Archaeology Meeting in Tromsø, highlighting its significance in understanding early reindeer hunting practices.

Archaeologist Leif Inge Åstveit is the project leader for the excavation of the mass trapping facility.

“It’s been incredibly busy,” project leader Leif Inge Åstveit told Science Norway. “It feels fantastic that our excavation was named Find of the Year.”

Åstveit acknowledged that Norway has seen numerous remarkable discoveries this year, making the competition for the award especially strong. However, their site ultimately won by a clear margin.

“This discovery is truly exceptional,” he said. “The level of preservation is unlike anything we normally encounter, which makes it remarkable.”

He added that the find has attracted massive attention. “It’s been a whirlwind. We receive multiple inquiries every day, both from within Norway and internationally. The experience has been very unusual,” Åstveit said.

Archaeologists also found a wooden oar decorated with carved ornamentation.

A one-of-a-kind discovery

Archaeologist Erik Kjellmann, who led this year's Norwegian Archaeology Meeting (NAM), believes the find won the award because of its exceptional nature.

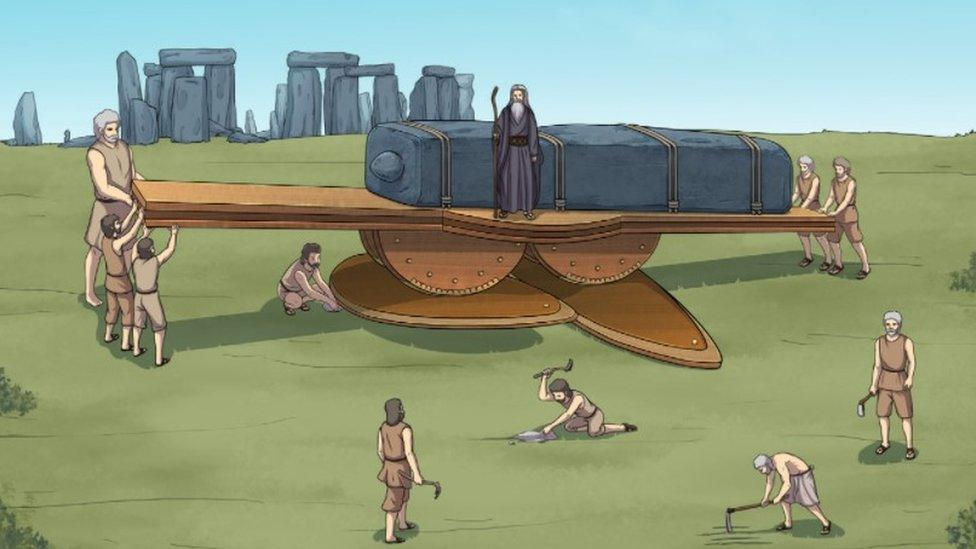

“Never before in Norway have such well-preserved remains of what appears to be a wooden trapping facility been uncovered,” he said.

Kjellmann emphasized that the materials already recovered offer enormous potential for new insights, and that the remaining ice likely conceals even more discoveries.

“Finds like this capture the imagination and excitement of archaeologists, which probably contributed to its recognition,” he explained.

He also highlighted the extraordinary state of preservation. “The objects displayed at NAM looked as if they were made yesterday. Wood usually doesn’t survive well in soil, but ice creates near-perfect conditions for preserving materials over thousands of years,” Kjellmann said.

The road ahead

Project leader Leif Inge Åstveit shared that the team plans to continue with a dating program, analyzing tree rings in the wood to determine the exact age of the facility and the season when the trees were felled.

“Other trapping facilities have been found in the mountains before, but they were all built from stone, leaving very little for archaeologists to study. Finding organic material like this opens up an entirely new set of possibilities,” he said.