Later Hellenistic Leagues and the Legacy of Panhellenism

After Alexander’s untimely death in 323 BC, his empire fragmented and the direct political unity of the Greeks under a single hegemon was short-lived. Yet the ideal of Panhellenic unity and shared identity did not vanish. During the Hellenistic period (3rd–2nd centuries BC), new federations of Greek city-states emerged, most notably the Aetolian League and the Achaean League. These leagues, though regional rather than pan–Greek in scope, drew inspiration from earlier Greek alliances and maintained important aspects of cultural continuity.

The Aetolian League rose to prominence in Central Greece, originally a union of the Aetolian communities that expanded to include many other cities. It was a federal state (koinon) with its own assemblies and magistrates, demonstrating that Greeks could form a broader political structure while preserving local autonomy. The Aetolians, proud of their rugged independence, actively invoked Panhellenic themes to boost their standing. In 279 BC, when a horde of Gauls (Galatians) invaded Greece and threatened Delphi, the Aetolian League took the lead in defending the sacred site. The Gauls were repelled, and this feat was celebrated across Greece as a deliverance akin to the Persian War of old – Polybius even ranked it alongside the victories over Persia, and Pausanias later called the Gallic threat the greatest peril Greece had faced since Xerxes. In gratitude for saving Apollo’s sanctuary, the Delphic Amphictyonic Council admitted the Aetolian League as a member and granted it a place of honor in overseeing Delphi. The Aetolians then organized the Soteria (“Deliverance”) festival at Delphi, a new Panhellenic festival (with athletic and musical contests) commemorating the Greek victory over the barbarians. This was a deliberate echo of earlier Panhellenic games and helped project the Aetolians as inheritors of the legacy of Greek unity. Through their league, they championed themselves as protectors of Hellenism – even as they also used the league for expansion and power politics. Culturally, the Aetolian League’s prominence at Delphi and its festival of Soteria show a continuity of Panhellenic religious tradition: Greek states still came together for common worship and celebration of collective victories, now under Aetolia’s auspices.

The Achaean League, based in the Peloponnese, likewise provides an example of Greeks uniting in a federal structure with cultural cohesion. Revived in 280 BC, the Achaean League eventually bound together a dozen or more city-states including not just the Achaean heartland but cities like Corinth, Megalopolis, Argos, and others. It had a constitution with a federal assembly and annually elected strategos (general), pointing to a sophisticated attempt at shared governance among formerly independent cities. The league is often studied as an early model of federalism, demonstrating “how city-states could unite under a common political structure while retaining local autonomy”. Under dynamic leaders such as Aratus of Sicyon and later Philopoemen, the Achaean League not only fought wars (against Spartan kings and Macedonian interference) but also fostered a sense of collective identity among its members. They issued common coinage and coordinated policies, projecting an image of a unified Achaean state. Culturally, the member cities shared in religious festivals and traditions; for instance, the league likely sponsored games and observed common rituals (the Achaean assembly met at the sanctuary of Zeus Homarios at Aegium in early years, indicating a religious element to their unity). The League’s cultural contributions included economic and social integration of the Peloponnese and “fostering a sense of shared identity and cooperation among its member cities”. In many ways, the Achaean League attempted to revive the cooperative spirit of the Hellenic League, though on a regional scale and without a single monarch.

Despite the successes of these leagues in creating pockets of unity, they also highlight the limits of the Panhellenic ideal in an era dominated by powerful kingdoms and, eventually, Rome. The Aetolian and Achaean Leagues sometimes allied but often quarreled, and both leagues clashed with the Macedonian kings (and later with Rome) in struggles for power. Unlike the united front of 480 BC or the Macedonian-led league of Philip and Alexander, the Hellenistic leagues were parallel regional alliances – a testament to Greek resilience in self-organization, but also a sign that Greece remained politically fragmented. Even so, the endurance of these federations into the 2nd century BC demonstrated a continuity of the Panhellenic idea: the notion that Greeks were one people and should band together for common causes did not die. Members of the Achaean League, for example, saw themselves not just as citizens of their city but also as collectively “Achaeans,” and even used the league to negotiate as a single entity with foreign powers, much as a Panhellenic union might. In 146 BC, the Achaean League made a final, doomed stand against Rome in the Achaean War, a last echo of unified Greek resistance; its defeat and the sack of Corinth symbolically marked the end of Greek political independence. Yet even under Roman rule, the cultural concept of Panhellenism persisted – centuries later, the Roman Emperor Hadrian would establish a “Panhellenion” league of cities to hark back to the classical ideal of a unified Greece.

Conclusion

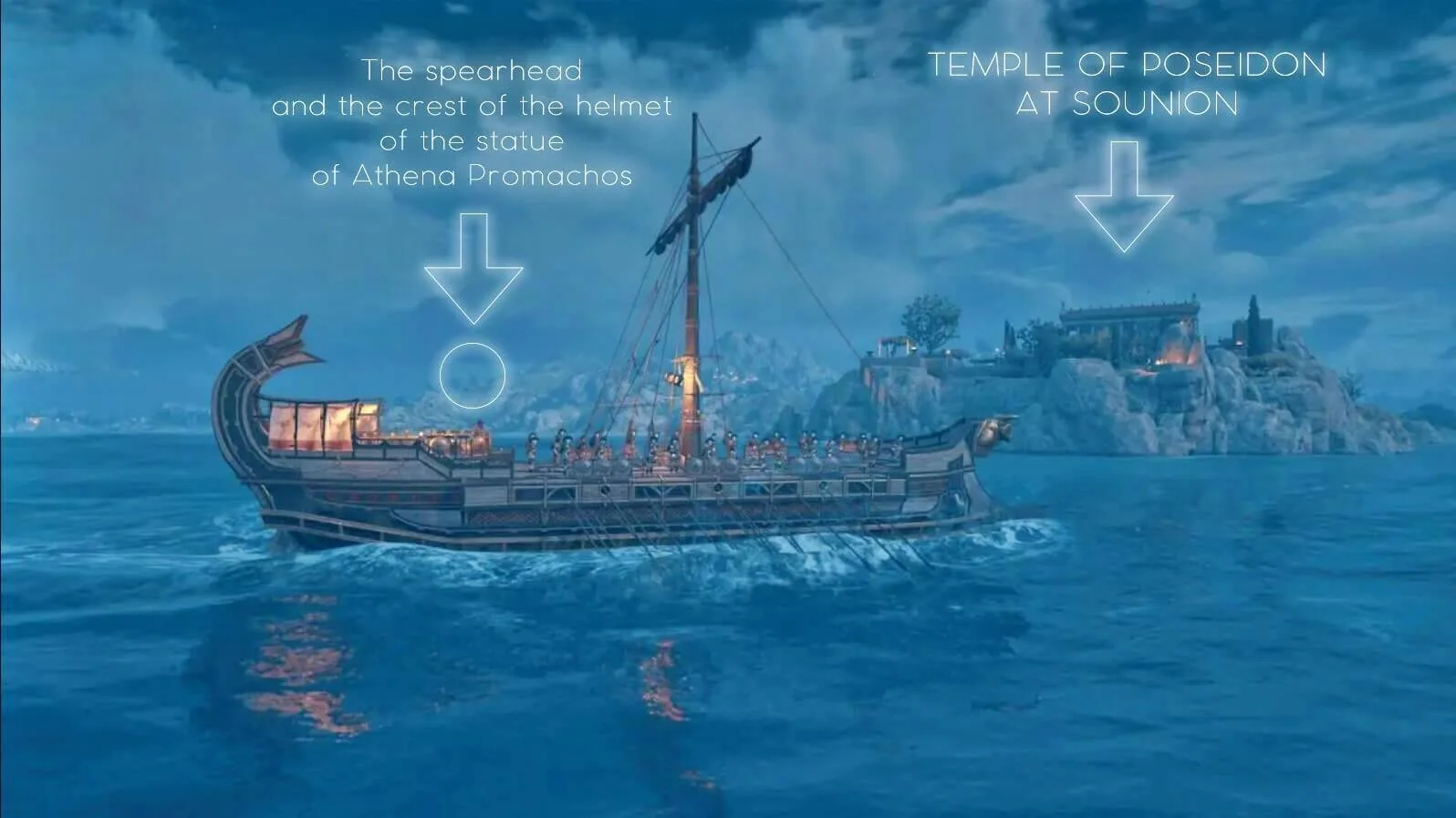

From the Persian Wars through the Hellenistic age, the Panhellenic ideal evolved in response to the needs of the time. Initially an ad hoc alliance for survival, it became an aspirational ideology used by leaders like Philip II and Alexander to legitimize conquest and empire-building as a form of collective Greek enterprise. Shared elements of culture and religion – common gods, sanctuaries, oracles, athletic games, heroic legends, and the age-old dichotomy of “Greek vs. barbarian” – were the glue that held this ideal together. These factors provided a sense of brotherhood among Greeks, even when political reality fell short of complete unity. Alexander the Great deftly leveraged Panhellenic traditions, from dedicating temples and treasures to Greek gods to guaranteeing the freedoms of Greek cities, thereby casting himself as the culmination of the Panhellenic dream of unity and revenge against Persia. The Priene Inscription is a tangible testament to how Alexander melded piety and policy to appeal to Greek sentiment – dedicating a temple to Athena and at the same time affirming his role as protector of Greek liberties.

The later federations of the Aetolians and Achaeans carried the torch of Greek unity in altered form, preserving the notion that Greeks could and should govern themselves cooperatively. While they never united all of Hellas, these leagues maintained cultural continuity with the Panhellenic ideal through federal institutions and the defense of common interests (such as safeguarding Delphi or resisting tyranny). In sum, the Panhellenic League was not a single continuous entity but rather a recurring vision – one that manifested in different guises from the stand at Thermopylae to the halls of Corinth, from Alexander’s edicts to the councils of the Achaean League. This vision of Greek unity grounded in shared heritage proved powerful and enduring, leaving a legacy that would inspire leaders and writers for generations and become an integral part of how the Greeks remembered their collective past.

References

Warfare History Network – Defending the Pass at the Battle of Thermopylae.

Sheldon, Natasha. The Temenos of Apollo, Delphi. History & Archaeology Online (2021).

Thomas R. Martin – An Overview of Classical Greek History from Mycenae to Alexander, Ch. 15, Sec. 19: “Isocrates on Panhellenism.”

Alexander’s Triumph at Granicus, Warfare History Network.