The discovery of Çatalhöyük, a sizable Neolithic settlement in central Turkey, in the late 1950s captivated the archaeological community. The site, which British archaeologist James Mellaart discovered, provided a remarkable window into early human civilization. Çatalhöyük, dating back nearly 9,000 years, is renowned for its densely packed mud-brick houses, its vibrant wall paintings, and its remarkable collection of figurines and artifacts. Among these findings, one particular mural unearthed during Mellaart’s 1960s excavations has sparked significant debate and intrigue—a painting that might represent the world’s oldest depiction of a volcanic eruption.

The Discovery of a Neolithic Enigma

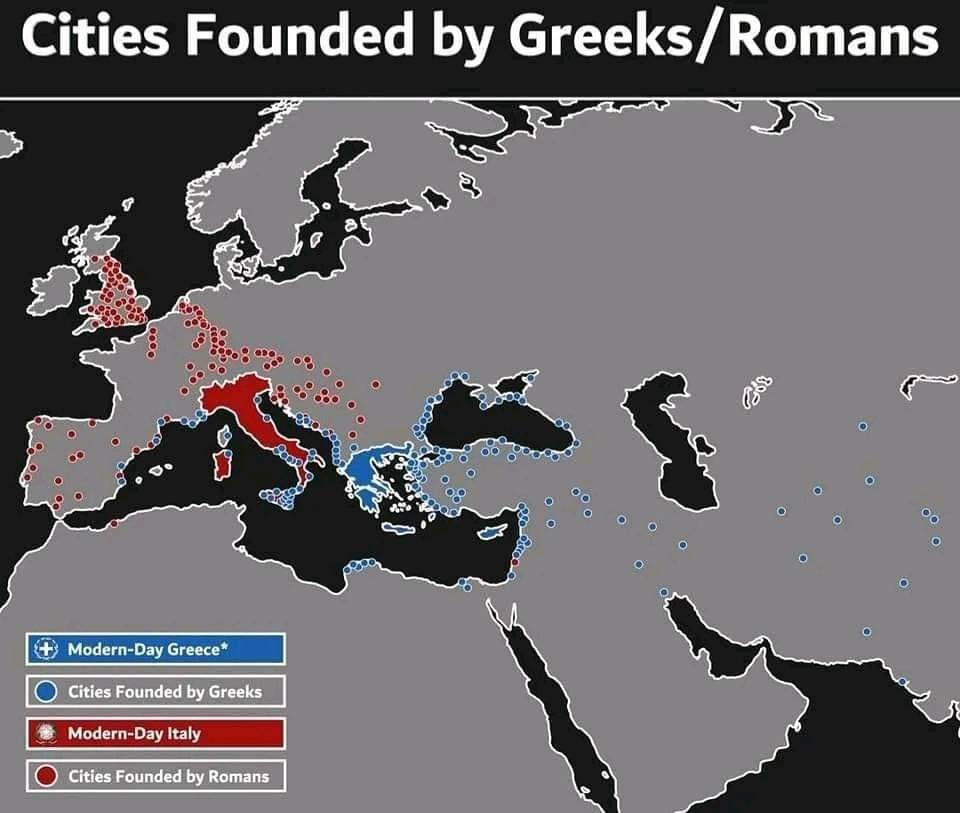

Could this Catalhoyuk mural, now faded with age, be the world's oldest map?

Keith Clarke/UCSB

The mural in question, discovered on the wall of a structure within this ancient proto-city, caught Mellaart’s attention due to its unique composition. He perceived it to be a town plan for a Neolithic village under the shadow of a twin-peaked volcano that was erupting with ash and lava. This interpretation suggested that the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük had not only witnessed a volcanic eruption but also felt compelled to record this dramatic event on their walls. Mellaart’s hypothesis was revolutionary, proposing that this painting could be the earliest known map and the oldest visual representation of a natural disaster.

However, this interpretation was not without controversy. As the mural became more widely studied, alternative theories emerged. Some scholars argued that the so-called volcano could actually be a stylized representation of a leopard’s skin, a motif found elsewhere at Çatalhöyük. The supposed map of the village they suggested might be nothing more than a geometric pattern, similar to other abstract designs prevalent at the site. This debate highlighted the inherent challenges of interpreting ancient art, where meanings are often ambiguous and open to multiple interpretations.

New Evidence and Renewed Debates

For decades, the debate over the Çatalhöyük mural remained unresolved. The controversy surrounding its interpretation was reignited in the 2000s when modern scientific techniques were applied to the study of nearby geological formations. Volcanologist Axel Schmitt, from the University of California, Los Angeles, became particularly interested in Mellaart’s volcanic mural. Schmitt’s team sought to determine whether Hasan Dağ, the twin-peaked volcano near Çatalhöyük, had indeed erupted during the period when the mural was created.

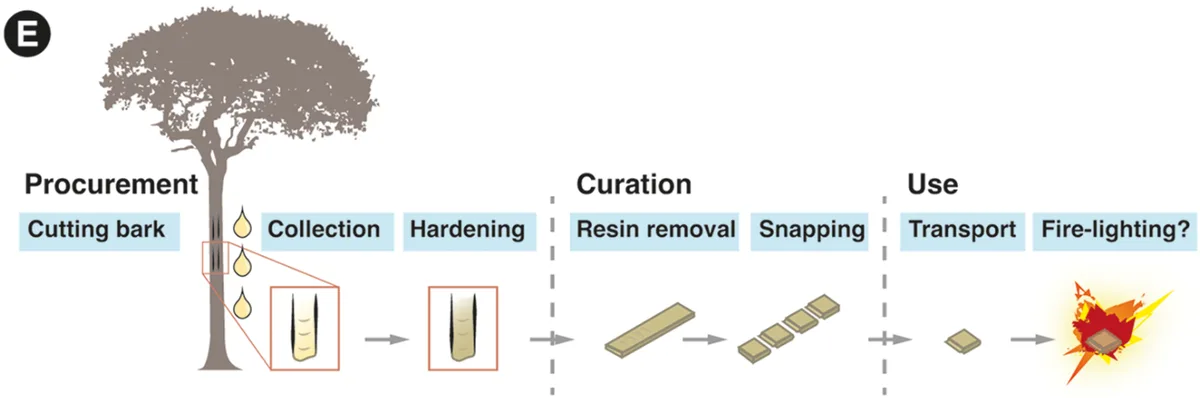

Schmitt’s approach involved the analysis of pumice samples collected from Hasan Dağ. Using advanced uranium-thorium-helium dating techniques on zircon crystals found within the volcanic deposits, his team was able to establish that the volcano had experienced a minor eruption approximately 9,000 years ago. This timeline closely aligns with the estimated date of the mural, suggesting that the painting could indeed depict a volcanic event witnessed by the people of Çatalhöyük.

An analysis of pumice samples from Turkey's Hasan Dagi mountain confirms the volcano did erupt around 9,000 years ago — within the rough time frame of when the mural is thought to have been painted.

Janet C. Harvey/PLoS ONE

The eruption identified by Schmitt’s team was likely a Strombolian-type event, characterized by relatively small but visually striking explosions. While not a cataclysmic eruption, it would have been a memorable and awe-inspiring spectacle for the Neolithic inhabitants. This scientific evidence provided new weight to Mellaart’s original interpretation, suggesting that the mural could be a depiction of Hasan Dağ erupting—a moment of natural drama immortalized on the walls of Çatalhöyük.

Interpreting the Past, Understanding the Present

The renewed debate over the Çatalhöyük mural underscores the complexities of interpreting ancient art and the challenges of reconstructing the thoughts and beliefs of early human societies. While Schmitt’s findings lend credence to the idea that the mural represents a volcanic eruption, alternative interpretations cannot be entirely dismissed. The image might still be a stylized depiction of a leopard skin or a geometric design unrelated to any natural event.

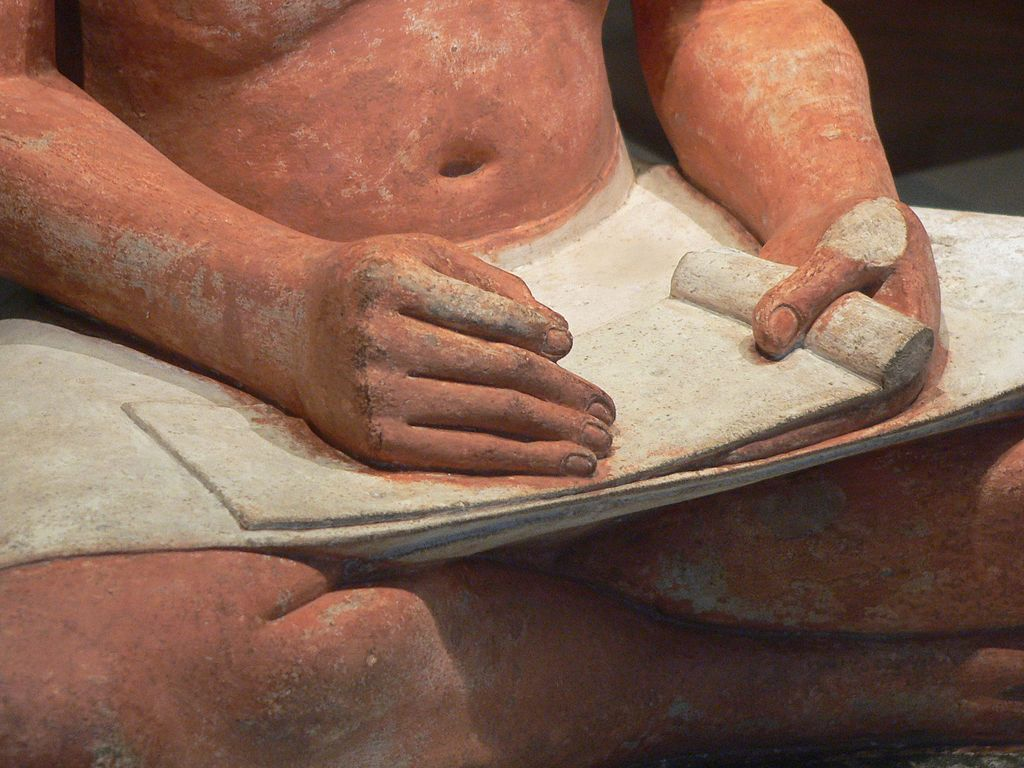

A reproduction of the mural from a room in Catalhoyuk, a Neolithic settlement in Turkey.

As Schmitt himself has noted, the people of Çatalhöyük lived in a world vastly different from our own, with a worldview shaped by experiences and beliefs that may be difficult for modern observers to fully comprehend. The mural could represent a blend of observed reality, myth, and symbolic expression, reflecting a cultural narrative that has long since been lost to time.

Tristan Carter, an archaeologist who has worked extensively at Çatalhöyük, supports the notion that a volcanic eruption would have been a significant event for the community. Such an occurrence might have been preserved through oral traditions—songs, stories, and rituals—eventually finding expression in visual form. If the mural does depict a volcanic eruption, it would not only be the earliest known representation of such an event but also one of the first instances of humans attempting to map and understand their environment through art.

The Çatalhöyük mural, whether it depicts an erupting volcano or not, remains a powerful symbol of early human creativity and the desire to document and make sense of the world. It stands as a testament to the ingenuity of our ancestors, who, in the midst of transitioning from nomadic hunter-gatherers to settled agriculturalists, found ways to express their experiences and environment through visual art. This enigmatic mural challenges us to consider how ancient peoples perceived their world and how they chose to communicate their understanding of it—a question that continues to fascinate and inspire scholars today.