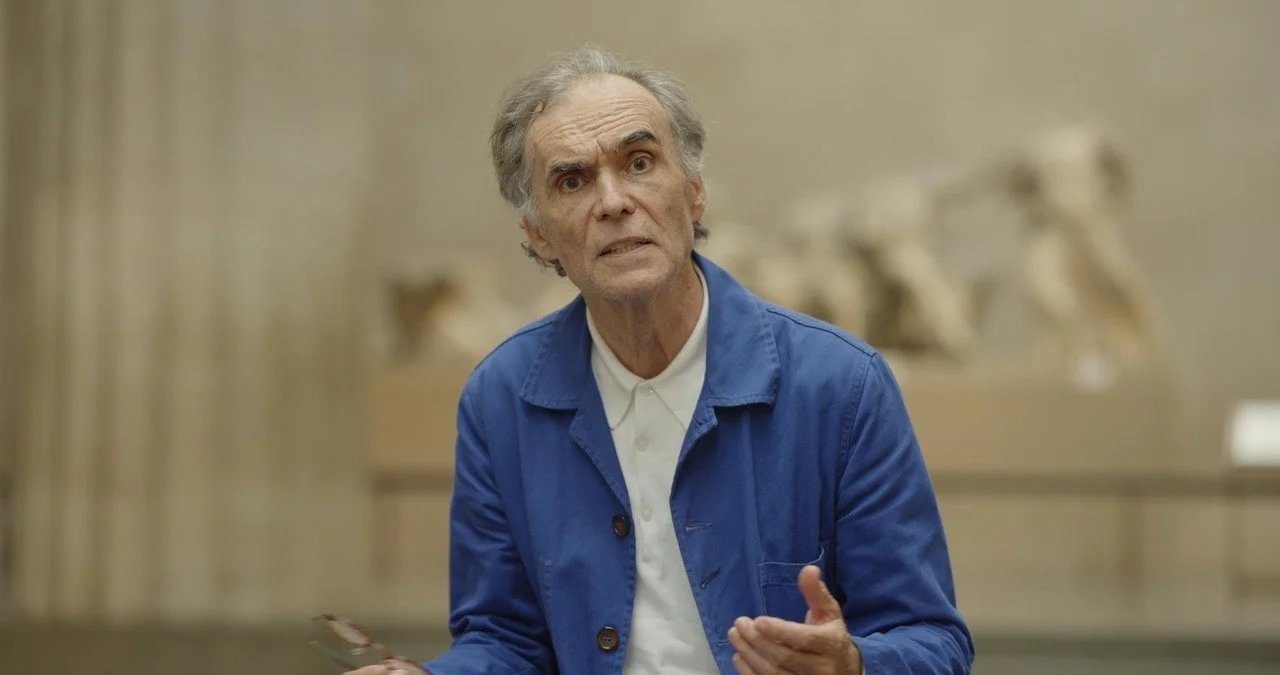

A public discussion titled “Who’s Afraid of the Ancient Greeks?” took place on October 8, 2025, in Brussels, as part of the cultural events organized by the MCC Brussels (Mathias Corvinus Collegium), a European think tank dedicated to the intellectual and cultural renewal of Europe. The panel featured three distinguished speakers: Dr. Benedict Beckeld, philosopher and author of Western Self-Contempt: Oikophobia in the Decline of Civilizations, Dr. Alexander Meert, historian and lecturer at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel and member of the Roman Society Research Center at Ghent University, and Dr. Maren Thom, researcher and film critic, Senior Research Fellow at MCC Brussels. The three academics engaged in a vivid dialogue about the significance of ancient Greek thought and education for contemporary European culture, exploring whether the West still recognizes its Hellenic roots or has become estranged from them in the name of postmodern sensitivity.

The event begins from a simple but often ignored premise: to understand Europe, one must look directly at Greece. Not as a museum relic, but as a living foundation of values, institutions, and intellectual tools that still function when we choose to use them. The introduction sets the stage clearly: Europe is not a bureaucratic invention or a random set of “principles” pulled out of administrative language. It is a historical continuum connecting Greece, Rome, Christianity, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment. Within that continuum, ancient Greece is not merely an early stage but the primary mechanism that generated and regenerated the very ideas we live by: freedom, risk, self-government, reason, and the union of tragedy and catharsis. The discussion is not nostalgic. It is political in the classical sense: it asks how we live together, how we learn, how we argue, how we transform.

The first argument, presented by Benedict Beckeld, begins with a question: does “the West” exist? His answer is calm and empirical. Not as a physical object, perhaps, but as a historical reality with recognizable forms, memories, models, and influences, absolutely yes. It is no coincidence that Virgil imitates Homer, or that Dante takes Virgil as his guide. The thread is visible in art, architecture, law, and political language. The concept of “the West” is not invalid just because it is abstract; history is made of such abstractions that shape real societies. From there, Beckeld argues that if the West exists, we must see ourselves in the Greeks. Not as marble statues, but as ancestors who faced the same human dilemmas. Athens knew relativism, atheism, moral fatigue, and social decay, just as we do. The debate between physis and nomos, the crisis of faith, and the exhaustion of civic life are recurring patterns. To read them in the Greeks is not anachronism, it is a way to understand our own condition without illusions.

A key point in Beckeld’s speech is the rejection of guilt about “Eurocentrism.” Pride in one’s own heritage is not racism. Just as a Chinese person can be Sino-centric without hostility toward others, a European can love and protect his own cultural forms. Civilizational self-hatred is a dead end. Merely reacting against “decadence” changes nothing. There must be a positive horizon: a clear sense of who we are and what we aim to become, not only what we reject. Here, Greece functions both as mirror and beacon. It shows us the height of achievement but also the depth of human weakness.

From philosophy, the discussion turns to how Greek thought became a machine of balance. Alexander Meert returns to the classical texts to show that Greek philosophy created a worldview that connected the physical and the metaphysical, experience and meaning. Modern discomfort, the thinning of meaning into mere functionality, has led to shallow cults of rationalism and empty substitutes for spirituality. Greek philosophy offers another path: openness that allows both wonder and logic, a sense of measure that avoids extremes, and a dialogical method that teaches us to disagree without destroying one another. The story of Gyges’ ring is not a fable; it is a warning about what happens when nature devours law, when power hides itself under invisibility. Athens lived through plague, impiety trials, and fanaticism, yet within this pendulum Greek philosophy acted as the conscience of society, alerting it to the danger of imbalance.

The essential Greek contribution, Mert continues, lies in the value of reason. Not reason as cold rationalism, but as a living habit of dialogue, of questioning and answering. Dialectic, open debate, frank speech, and equality before the law were not decorative virtues. They were the operating system of a civic order built for citizens, not subjects. When modern universities start using “trigger warnings” for the Iliad or the Odyssey, or quietly censor material “to protect students,” that is not sensitivity but a loss of the Greek principle of endurance in the face of truth. Greek education demanded the strength to face discomfort, not escape it. Mert also notes a practical issue: the decline of classical languages and the rise of ideological theories about “identity.” When education becomes a matter of slogans, we lose the discipline of argument and become prey to every passing fashion.

The artistic dimension enters through Maren Thom, who shifts the focus to Greek drama. She argues that modern censors attack not the content of Greek texts but their form and psychological power. Greek tragedy transforms the audience through conflict, fear, and pity. Catharsis is not therapy; it is the civic process through which citizens learn to face truth without collapse. That is why Athenians built theaters that held thousands and paid the poor to attend. Drama was not private entertainment. It was a civic duty and a form of collective education. The modern tendency to “sanitize” art, to remove what shocks or unsettles us, empties the very engine of drama. The Greek theater worked precisely because it wounded and healed at the same time. Removing that power does not make art safer, only weaker. Thom points out that the flattening of emotional experience in modern storytelling, from Hollywood to animation, has erased catharsis. What remains is affirmation without transformation, narrative without consequence. The result is not morality but boredom.

Some critics at the event raised a fair warning against reading modern categories back into the past. Indeed, the Greeks had no single word for “religion.” Their gods were not objects of belief but participants in ritual, woven into civic life. “Atheos” shifted its meaning across centuries: first “forsaken by the gods,” later “without belief in gods.” Understanding these nuances requires philological care. Yet, as Beckeld replied, recognizing historical difference does not forbid comparison. When Isocrates laments that people no longer believe in the gods, or when Plato in the Laws tries to regulate a collapsing moral order, we see societies struggling with the same fatigue of meaning. To study those reactions is not to distort history but to learn how intelligent cultures respond to their own crises.

Another theme of the debate was the strangeness of the Greeks. They are not just “like us.” Their world was radically different, and that difference educates us. Their concept of honor, their intimacy with war, their fusion of freedom and slavery, their humor and cruelty in the same breath, all challenge our moral comfort. That alien quality is exactly what makes Greek civilization worth studying. Good translations should keep that strangeness alive. Making Homer sound like a modern teenager flattens his power. The goal is not to make the Greeks resemble us but to make us reach up to them.

A member of the audience asked a blunt question: what can we actually do? The answer emerging from MCC Brussels was practical and cultural. Revive the classics in schools. Restore the teaching of Greek and Latin, or at least serious engagement with the texts in accurate translations. Make public exposure to theater and philosophy part of civic education again. Remove the intellectual infantilization of “sensitive content.” Normalize disagreement as a form of learning. Reclaim concepts like frank speech, equality before the law, and civic duty. And above all, craft a positive narrative: pride without arrogance, self-criticism without self-hatred.

The memory of risk also matters. The story of Salamis was highlighted as the perfect symbol: the Athenians chose to abandon their city and fight at sea. They won not through generals or aristocrats but through sailors, the common people. After victory, they demanded political rights. That link between action and institution, courage and citizenship, is the Greek inheritance. Forget it, and democracy becomes a word without substance. Remember it, and it becomes strength again.

In answering those who accuse Greek civilization of racism, sexism, or “white supremacy,” the best response is twofold. First, scientific: do not fear the texts, read them fully, and reject the temptation to project modern categories backward. Second, educational: remind ourselves that truth often wounds before it enlightens, and that art exists to make us stronger, not safer. If we remove catharsis from art and philosophy, we do not produce sensitive societies but fragile ones.

The defense of Greek civilization, as presented in Brussels, is not reactionary nostalgia. It is an argument for courage in intellect and in aesthetics. Greece is not only admiration for beauty. It is, as one speaker put it, the pursuit of the future: playful creativity, democratic invention, balance between reason and reverence, war and wisdom, household and public square. To sever Europe from this root is to build a continent that is poorer, smaller, and easier to manage. MCC Brussels proposes the opposite: a Europe reconnected with its first workshop of the mind. There, the citizen is shaped again and again through speech, action, and transformation.

If this event leaves one clear message, it is that Greek civilization is not just one influence among many. It is our starting archive. From it, we learn to be Europeans without guilt and without arrogance, ambitious yet measured. Every time our age tries to sterilize education or flatten art, ancient philosophy and tragedy remind us of our duty: to stand upright within conflict and emerge changed, a little freer, a little wiser, a little more capable of carrying the weight of our shared city.