By The Archaeologist Editor Group

Sanctuaries of Syncretism: Deciphering Egyptian-Kushite Spiritual Connections

Jebel Barkal, a small mountain located in modern-day Sudan, has long been shrouded in the mystique of ancient history. This site, deeply intertwined with the religious and political dynamics of the ancient kingdoms of Egypt and Kush, hosts the remarkable Temple of Amun. The temple's rich history, architectural splendor, and the artifacts unearthed there offer invaluable insights into the religious and cultural practices of the time.

Historical Context

Jebel Barkal's prominence is largely attributed to its association with Amun, a major deity in Egyptian mythology. The site's significance escalated during the New Kingdom of Egypt (circa 1550–1077 BCE), when Pharaoh Thutmose III extended Egyptian influence into Nubia and identified Jebel Barkal as the dwelling of Amun. This association transformed Jebel Barkal into a spiritual epicenter, linking it directly to the Karnak Temple in Thebes, the primary cult center of Amun.

The Temple of Amun

The Temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal, primarily constructed during the reign of Ramses II, is a testament to the religious fervor and architectural ingenuity of the period. The temple complex, adorned with intricate carvings, colossal statues, and imposing pillars, was dedicated to the worship of Amun. It served as a spiritual and administrative hub, underscoring the interwoven nature of religion and governance in ancient Egypt and Kush.

Architectural Features and Artifacts

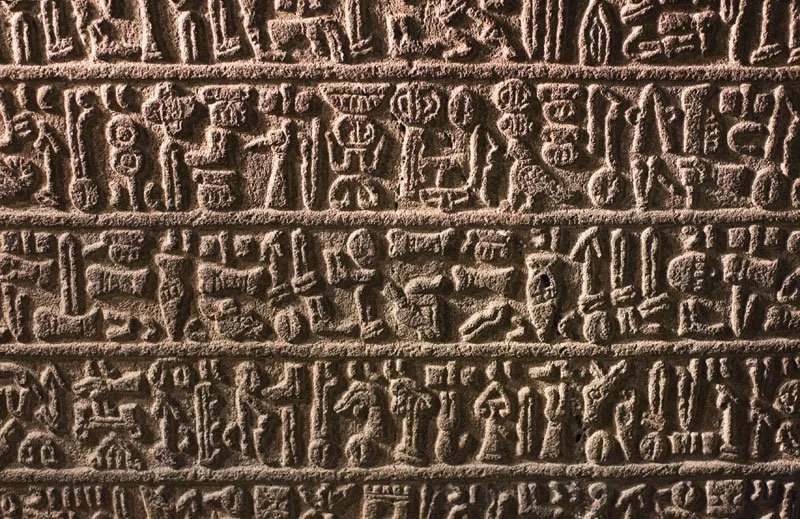

The temple's architecture is a blend of Egyptian and Kushite styles, reflecting the cultural exchange between the two civilizations. Notable features include the pillared hall, the sanctuary, and a series of chambers used for religious ceremonies. The temple walls are adorned with reliefs depicting various pharaohs making offerings to the gods, symbolizing the divine rights of kings.

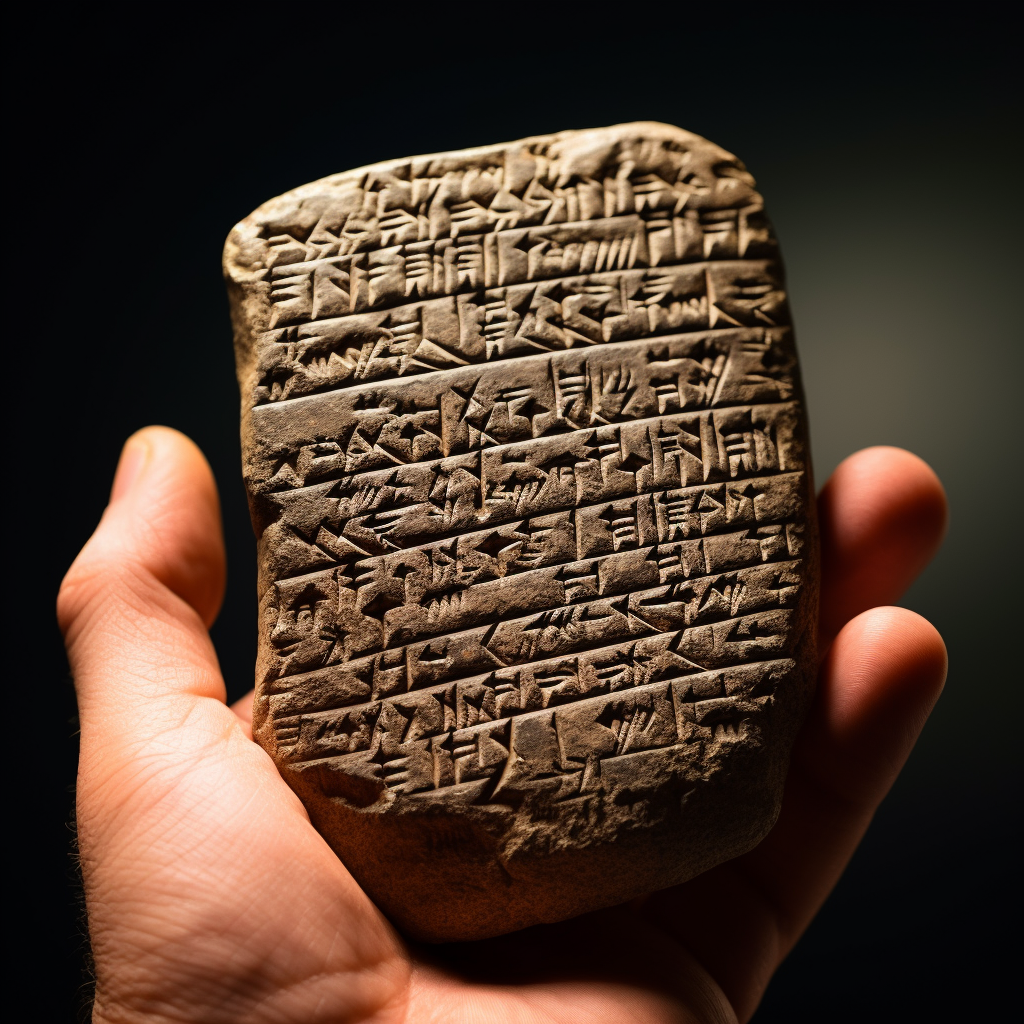

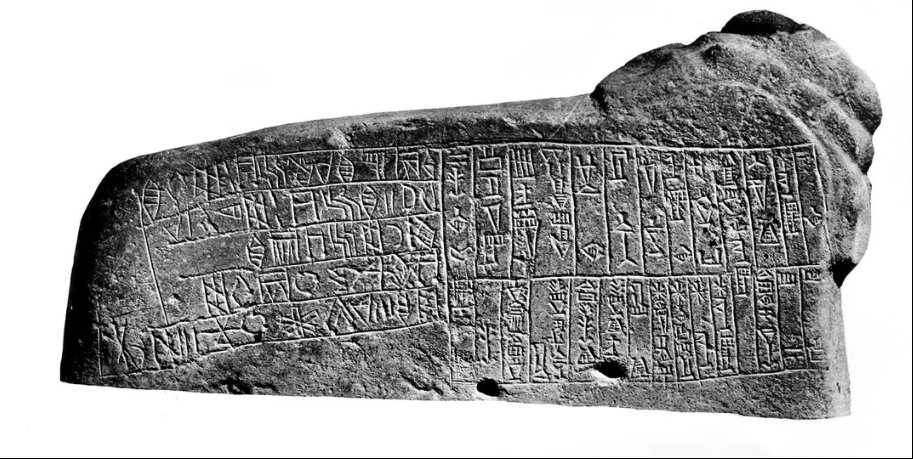

Excavations at Jebel Barkal have yielded a plethora of artifacts, including statues, stelae, and inscriptions. These findings provide crucial insights into the religious practices, art, and politics of the era. The artifacts also highlight the craftsmanship and artistic skills of the ancient artisans.

Jebel Barkal at Abu Simbel

The depiction of Jebel Barkal at Abu Simbel, another monumental temple complex located in Egypt, further underscores its religious significance. The imagery shows Jebel Barkal as a sacred mountain occupied by Amun of Karnak. The pinnacle of Jebel Barkal is often represented as a colossal royal uraeus (a rearing cobra), adorned with the White Crown, a symbol of pharaonic authority and divine protection.

(Left) The Jebel Barkal pinnacle viewed from the northeast (i.e. upstream, looking downstream); (right) Jebel Barkal, from the same angle, as pictured at Abu Simbel, showing it as a mountain occupied by Amun of Karnak and the pinnacle as a colossal royal uraeus wearing the White Crown.

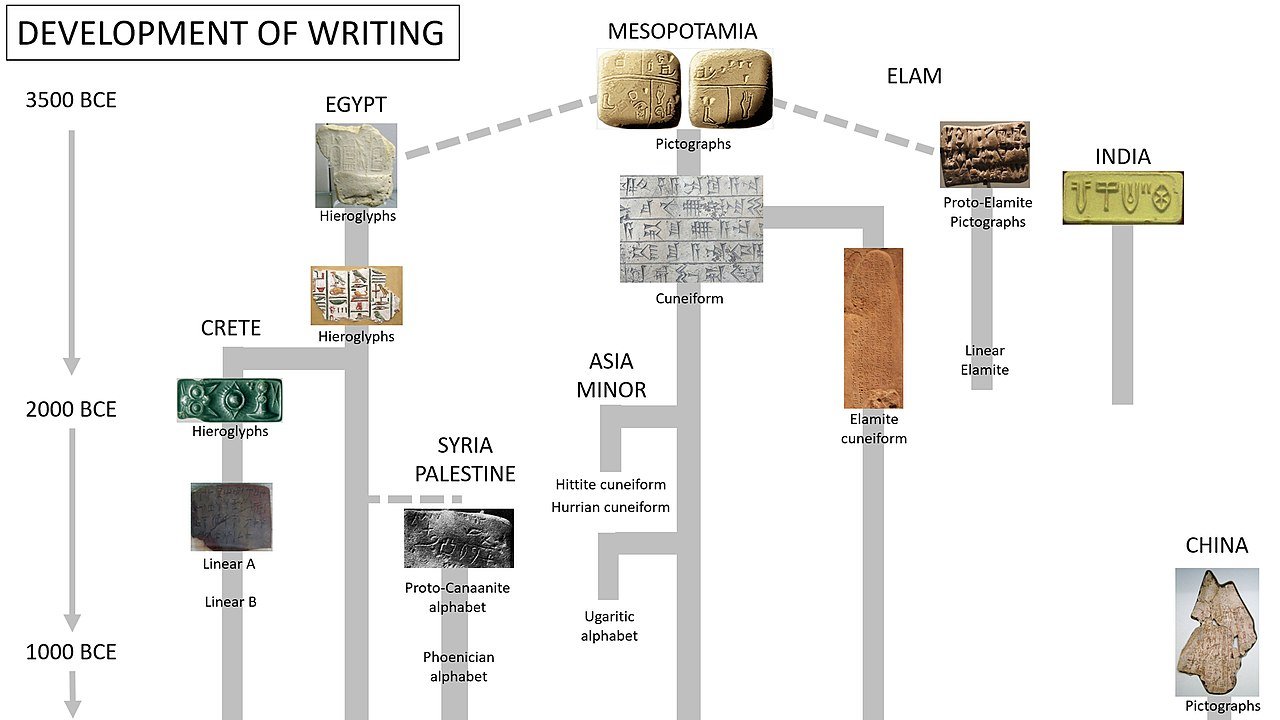

Egyptian-Kushite Religious Syncretism: A Confluence of Beliefs

The relationship between ancient Egypt and Kush, particularly in the realm of religion, is a fascinating example of cultural and religious syncretism. From around 2000 BCE, when Kush began to emerge as a significant power, there was a gradual blending of religious practices and deities between the two civilizations. This syncretism was not merely an adoption of Egyptian gods by the Kushites; rather, it represented a mutual exchange and reinterpretation of religious ideas and rituals. The Kushite interpretation of Egyptian deities often involved merging them with native Kushite gods or adapting their characteristics to fit local beliefs. For instance, the Egyptian god Amun, originally a minor deity, was assimilated with the Kushite god Apedemak, resulting in a unique form of worship that was distinctly Kushite while retaining Egyptian influences. This hybridization of religious beliefs is evident in the art and architecture of the period, where Egyptian styles blend seamlessly with indigenous Kushite elements, creating a distinct cultural identity.

The Impact of Syncretism on Political and Social Structures

This religious syncretism had significant implications for the political and social structures in both Egypt and Kush. In Egypt, the Kushite pharaohs of the 25th Dynasty embraced Egyptian religious traditions, incorporating them into their rule, which helped legitimize their reign in the eyes of the Egyptian populace. Conversely, in Kush, the adoption and adaptation of Egyptian religious practices served to enhance the authority and divine status of Kushite kings. This mutual religious influence fostered a sense of shared identity and cultural unity, despite the geographical and political distinctions between the two regions. Temples such as those at Jebel Barkal and the widespread worship of gods in their syncretized forms became symbols of this intertwined relationship. This syncretism also facilitated diplomatic and trade relationships, as shared religious beliefs often led to a deeper mutual understanding and respect between these ancient civilizations. Thus, the Egyptian-Kushite religious syncretism was not just a merging of gods and rituals but a profound blending of cultures that shaped the political and social landscapes of the region for centuries.

Jebel Barkal and its pinnacle as seen today through the ruined hypostyle hall of the Great Amun Temple.

The Temple of Amun at Jebel Barkal stands as a monumental testament to the religious and political landscape of ancient Egypt and Nubia. Its architectural grandeur, the rich array of artifacts uncovered, and its depiction in other significant Egyptian sites like Abu Simbel all highlight its importance as a cultural and religious nexus. Today, Jebel Barkal continues to captivate historians, archaeologists, and enthusiasts alike, offering a window into a world where the divine and the temporal intersect in profound ways.