Myth Versus Reality: How the Nazca Lines Were Truly Meant to Be Seen

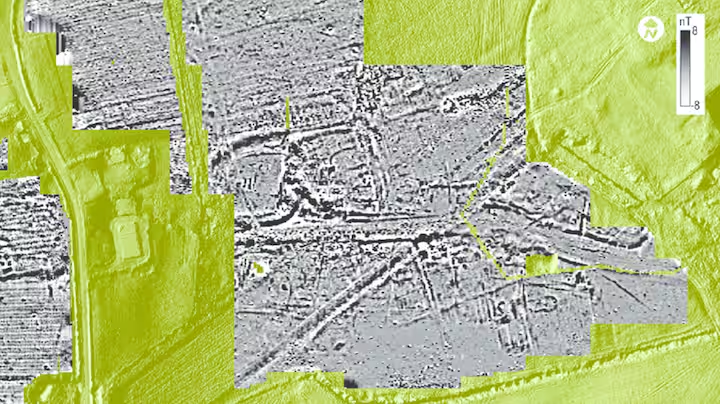

The arid plains of Peru’s Nazca Desert hold one of the world’s most enigmatic archaeological enigmas: the Nazca Lines. These colossal geoglyphs, created by the Nazca culture between 500 BCE and 500 CE, consist of hundreds of figures ranging from geometric patterns to stylized images of animals, plants, and mythical shapes. Stretching across nearly 450 square kilometers, these lines have puzzled historians, archaeologists, and enthusiasts for decades.

Origins and Discovery

The Nazca Lines were not widely known until the 20th century, when airplanes flying overhead revealed the vast and intricate designs etched into the landscape. This discovery propelled a myriad of theories about their purpose and creation, transforming them into a focal point for both scientific research and popular speculation.

Visibility and Purpose

One of the most striking aspects of the Nazca Lines is that they can be seen from the surrounding hilltops and even more distinctly from the Andes mountains nearby. This visibility refutes the more fantastical theories that claim only gods or extraterrestrial beings should be able to see the lines from above. Instead, it suggests that the Nazca people designed these geoglyphs with both an understanding and an appreciation of their natural landscape.

Archaeologists have proposed that the lines served a multifaceted set of purposes, blending the practical with the spiritual. Some suggest that the lines functioned as astronomical markers, aligning with key celestial events, which were critical in an agricultural society dependent on the seasonal cycles. Others believe the lines were part of ritualistic processes, perhaps used as sacred paths during religious ceremonies dedicated to deities who controlled fertility and water, crucial elements in the harsh desert environment.

Construction Techniques

The method of their creation is equally impressive. The geoglyphs were formed by removing the reddish pebbles that cover the terrain to reveal the lighter earth beneath. This technique not only required laborious effort but also an intricate knowledge of geometric design and spatial organization. The precision of the lines, some stretching up to several kilometers in length, showcases Nazca's sophisticated understanding of mathematics and surveying.

Debunking the Mythical

The visibility of the geoglyphs from nearby highlands also debunks more speculative theories, such as those suggesting the Nazca used hot air balloons to survey their constructions. Mainstream archaeology considers these theories a distraction from the true ingenuity of the Nazca culture. The lines were likely not meant for the gods in the sky but for rituals observed by participants walking along the paths, engaging directly with the figures etched into the earth.

Legacy and Preservation

Today, the Nazca Lines are a UNESCO World Heritage Site, protected and studied as precious relics of human creativity and ingenuity. The ongoing challenge is to preserve these vulnerable designs from threats such as climate change, erosion, and human activities. The lines have survived centuries, and with careful preservation, they can continue to fascinate and inspire generations to come.

The Nazca Lines remind us of the human capacity to reshape our environment into profound cultural expressions. These geoglyphs are not messages to be read from the heavens but monumental artworks that speak of the human spirit, ingenuity, and the eternal desire to commune with the cosmos.