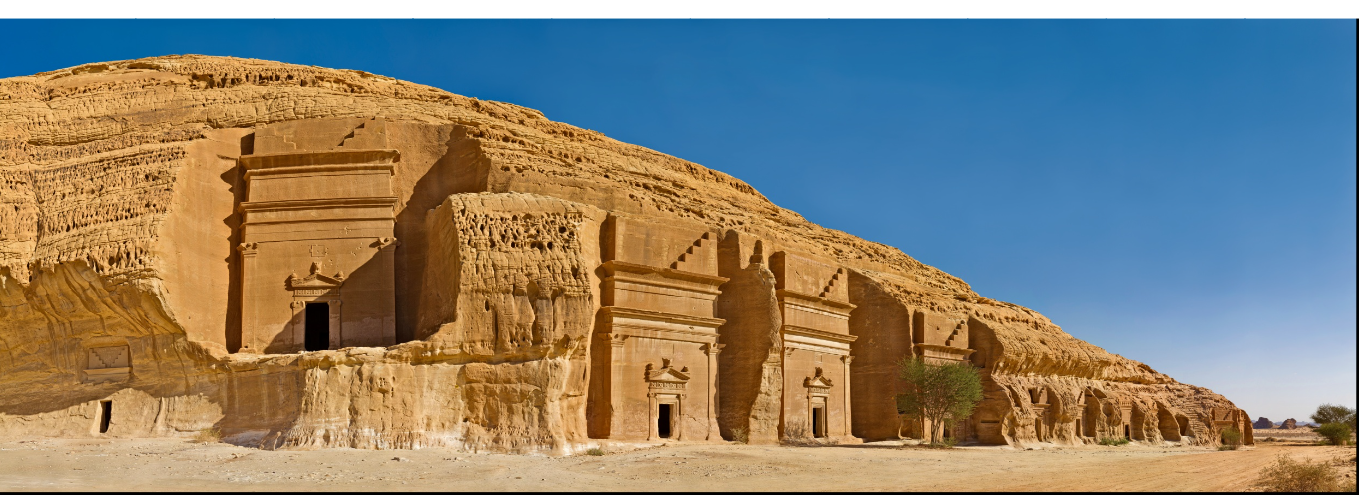

When Saudi Arabia opened its doors to non-Muslim international tourists in 2019, it unveiled a hidden gem: Mada’in Saleh, an archaeological wonder also known as Hegra. This 2,000-year-old Nabatean city, located in the Medina Province of Saudi Arabia, bears striking resemblances to Jordan's Petra but offers a more serene and less crowded experience. In this article, we will delve into the captivating world of Hegra, exploring its significance, history, accessibility, and more.

Where is Hegra, and How Do I Get There?

Hegra, or Mada’in Saleh, is situated in the Medina Province, nestled within the Hejaz region of Saudi Arabia. To reach this remarkable site, travelers can fly to the city of AlUla, which boasts an international airport with convenient connections to Dubai, Riyadh, Jeddah, and Damman. From AlUla, it's a mere 35-minute drive (approximately 26 miles) to reach Hegra. Moreover, visitors to Hegra will find themselves just 11.6 miles away from the astonishing Maraya Concert Hall, the largest mirrored building in the world, making it an ideal destination for cultural enthusiasts.

Are Petra and Mada’in Saleh the same?

While Petra and Mada’in Saleh (Hegra) share striking similarities, they are distinct archaeological sites located in different countries. Petra graces Jordan, while Mada’in Saleh resides in Saudi Arabia. Both sites, however, bear witness to the architectural prowess of the Nabateans, an ancient Arab people who once dominated the caravan trade in the Arabian Peninsula. Petra served as the Nabatean Kingdom's capital and largest city, while Mada’in Saleh was its second-largest settlement. The common thread between these sites lies in their captivating Nabatean rock-hewn monuments, featuring highly adorned tombs. Both also showcase the Nabateans' ingenuity in water management, evident through structures such as wells, water tunnels, cisterns, and reservoirs.

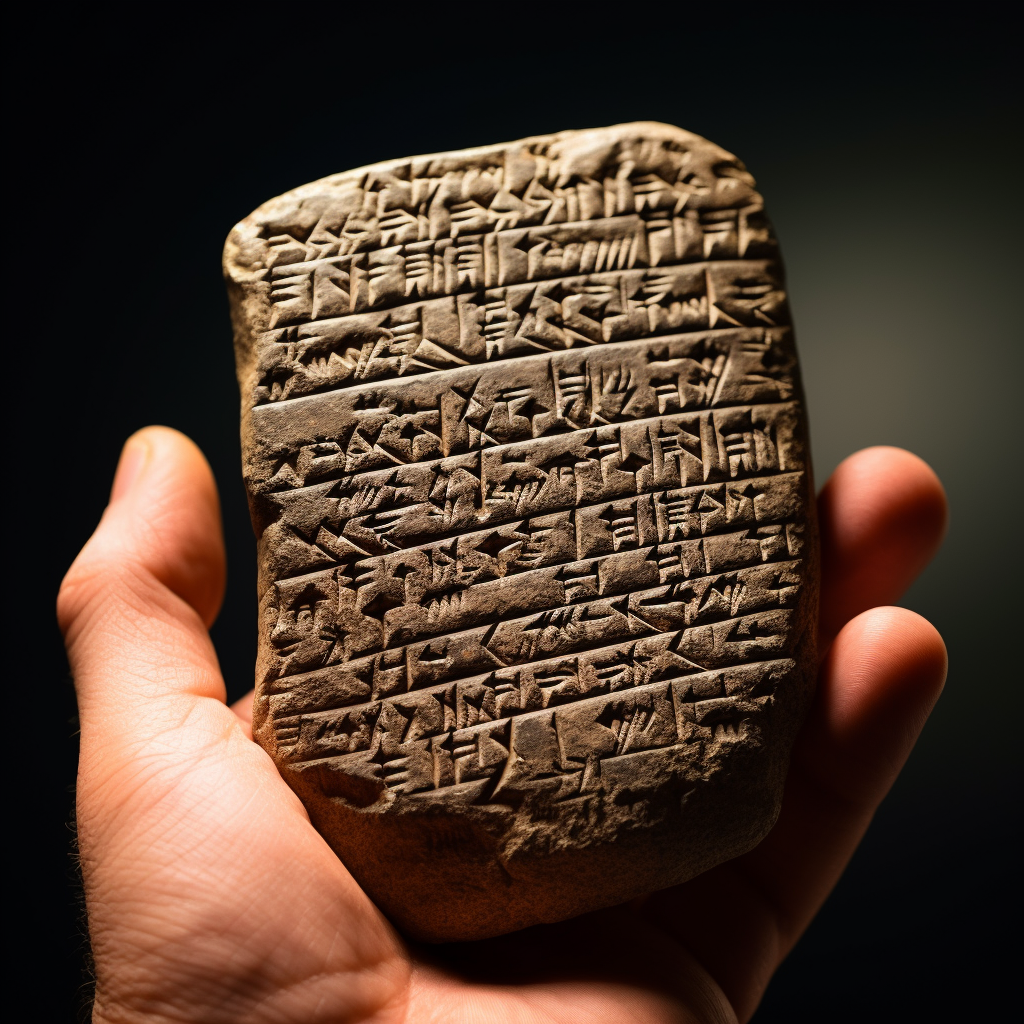

Photo: Lubo Ivanko/Shutterstock

The Significance of Hegra or Mada’in Saleh

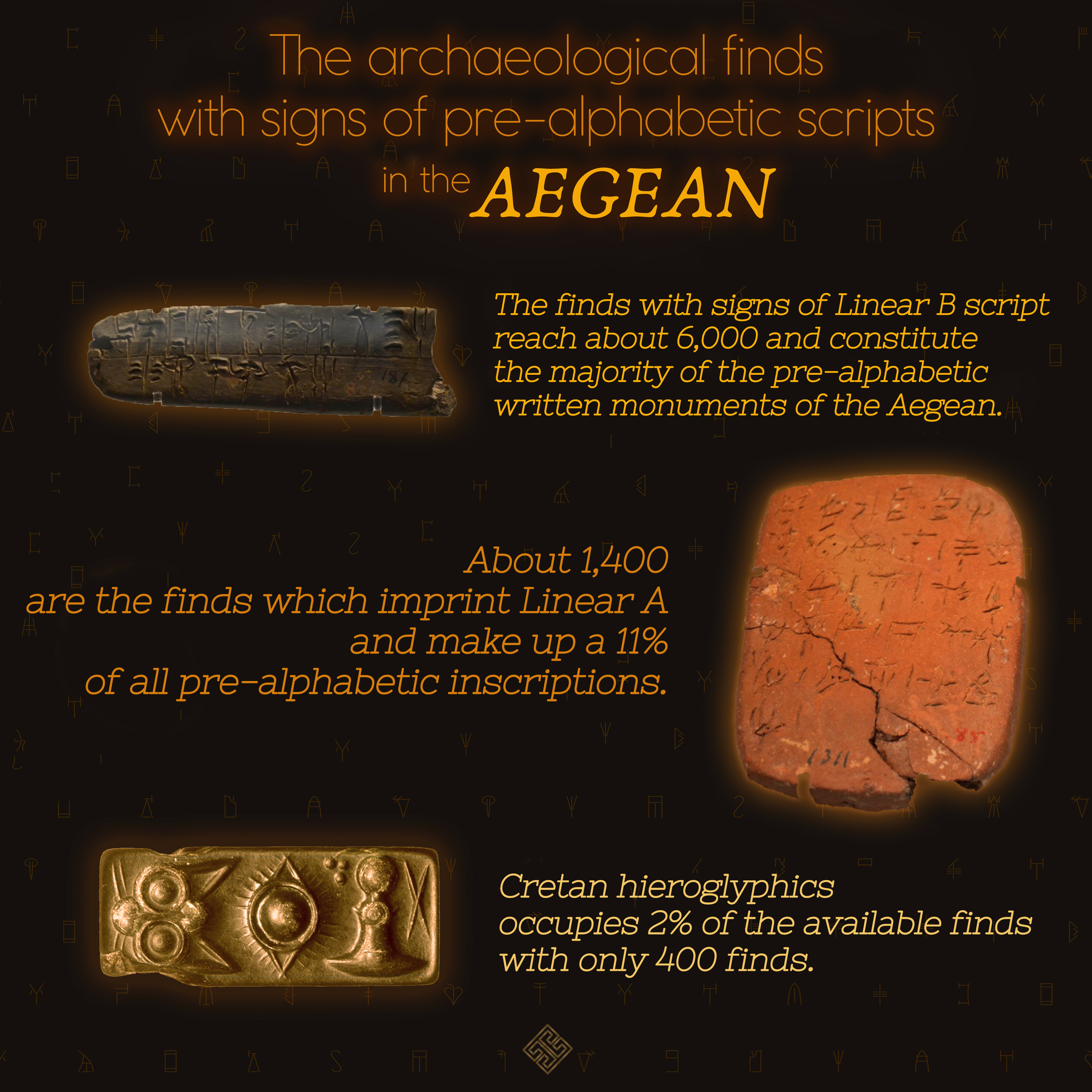

Mada’in Saleh, known as Hegra, stands as an immense and exceptionally well-preserved archaeological site in northwestern Saudi Arabia. It represents one of the most extensive remnants of the Nabatean civilization, an ancient nomadic people who eventually settled in Jordan during the fourth century BC, giving rise to Petra. At its zenith, the Nabatean Kingdom spanned across regions in Jordan, Israel, Egypt, Syria, and Saudi Arabia.

While Mada’in Saleh began as a city, it eventually evolved into a necropolis, or a vast cemetery. Today, the site's stunning rock-cut structures comprise 111 tombs constructed between the first century BC and the first century AD. Among these, the iconic 72-foot-tall Qasr al-Farid, known as the Lonely Castle, stands out. Additionally, remnants of rock-hewn water wells provide evidence of the Nabateans' expertise in water harvesting and conservation within the desert landscape.

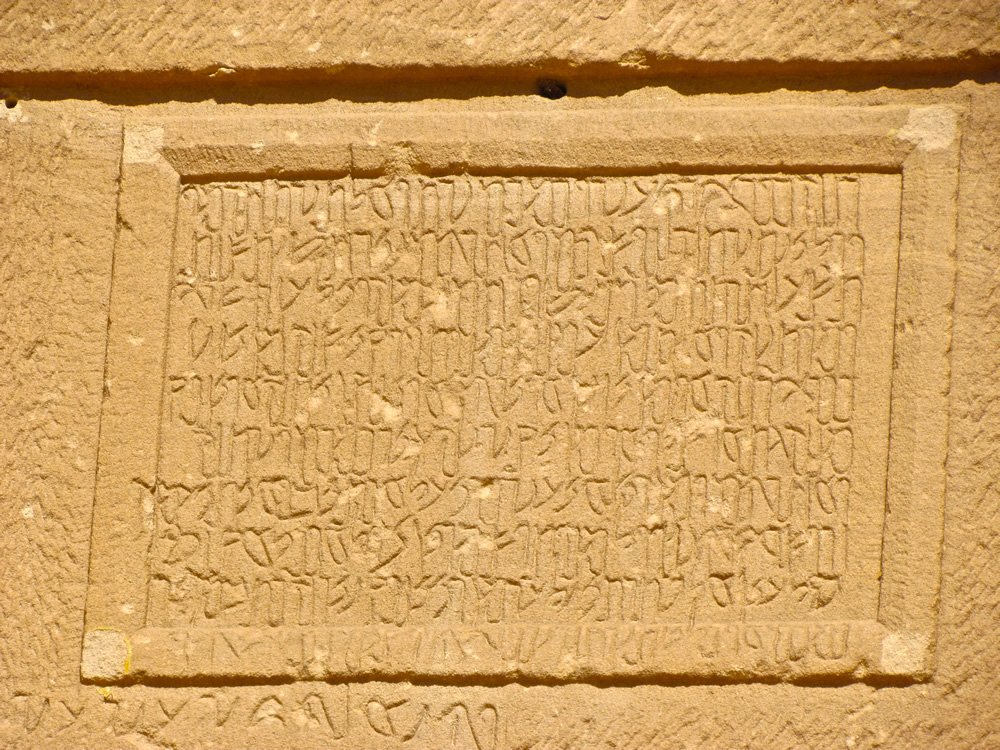

Beyond its impressive tombs, UNESCO recognizes Mada’in Saleh for its pre-Nabatean inscriptions and cave drawings, offering insights into human presence preceding the Nabatean civilization.

Hegra: Saudi Arabia's First UNESCO World Heritage Site

In 2008, Hegra, also known as Mada’in Saleh, achieved the distinction of becoming Saudi Arabia's first UNESCO World Heritage site. Today, Saudi Arabia boasts seven UNESCO-listed sites and an additional 14 sites on the tentative list. The seven UNESCO-listed sites are as follows:

Hegra Archaeological Site

At-Turaif District in ad-Dir’iyah

Historic Jeddah

Rock Art in the Hail Region of Saudi Arabia

Ḥimā Cultural Area

Al-Ahsa Oasis

‘Uruq Bani Ma’arid

The most recent addition to Saudi Arabia's UNESCO list is 'Uruq Bani Ma’arid, inscribed in 2023, further showcasing the nation's rich cultural heritage and historical significance.

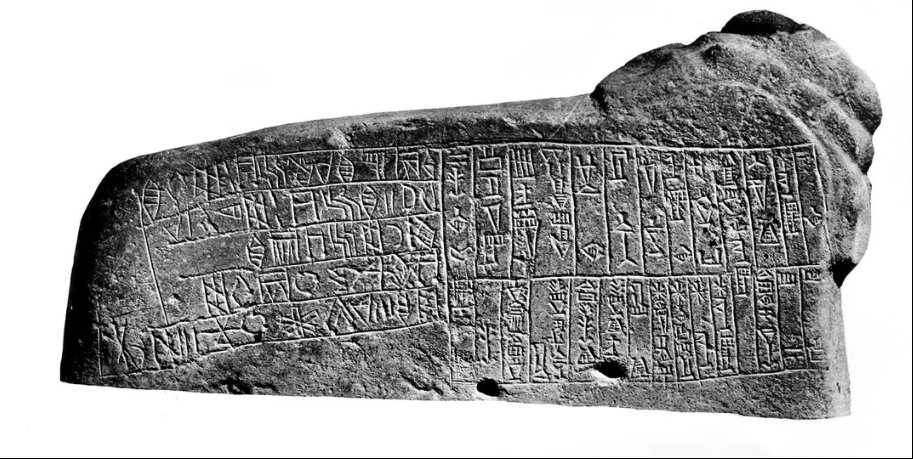

Photo: Lubo Ivanko/Shutterstock

The History of Mada’in Saleh in Saudi Arabia

The rock-cut monuments of Mada’in Saleh, or Hegra, span from the first century BC to the first century AD, a testament to the achievements of the Nabatean people. During this era, Saudi Arabia as we know it did not exist, and the Arabian Peninsula was inhabited by various peoples. Mada’in Saleh predates the advent of Islam by many centuries; the revelations to Prophet Muhammad in Mecca occurred in the year 610. Subsequently, Islam spread across the globe, and by the eighth century, the Islamic Empire extended from Spain to China. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, as we know it today, was established on September 23, 1932. Notably, the Nabateans were not the first inhabitants of Saudi Arabia, with evidence of human presence dating back 15,000 to 20,000 years.

Can Muslims visit Mada’in Saleh?

In the past, Mada’in Saleh and the surrounding AlUla region were believed to be cursed and haunted by jinn, malevolent spirits in Arab folklore. It was even believed that Prophet Muhammad had warned against visiting this area. However, in the contemporary era, as Saudi Arabia emerges as a prominent tourist destination, the curse has largely been relegated to history. Today, Muslim and non-Muslim visitors alike are encouraged to explore the beauty of this region.

It is essential to note that while Mada’in Saleh welcomes tourists of all backgrounds, the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, located in Saudi Arabia, remain restricted to non-Muslim visitors.

Hegra, or Mada’in Saleh, offers a captivating journey into the past, showcasing the marvels of the Nabatean civilization and the rich history of Saudi Arabia. As Saudi Arabia continues to open its doors to the world, this UNESCO World Heritage site stands as a testament to the nation's cultural heritage and historical significance, inviting travelers from all walks of life to explore its wonders.