Unveiling the Mysteries of Plimpton 322: A Babylonian Marvel in Mathematical History

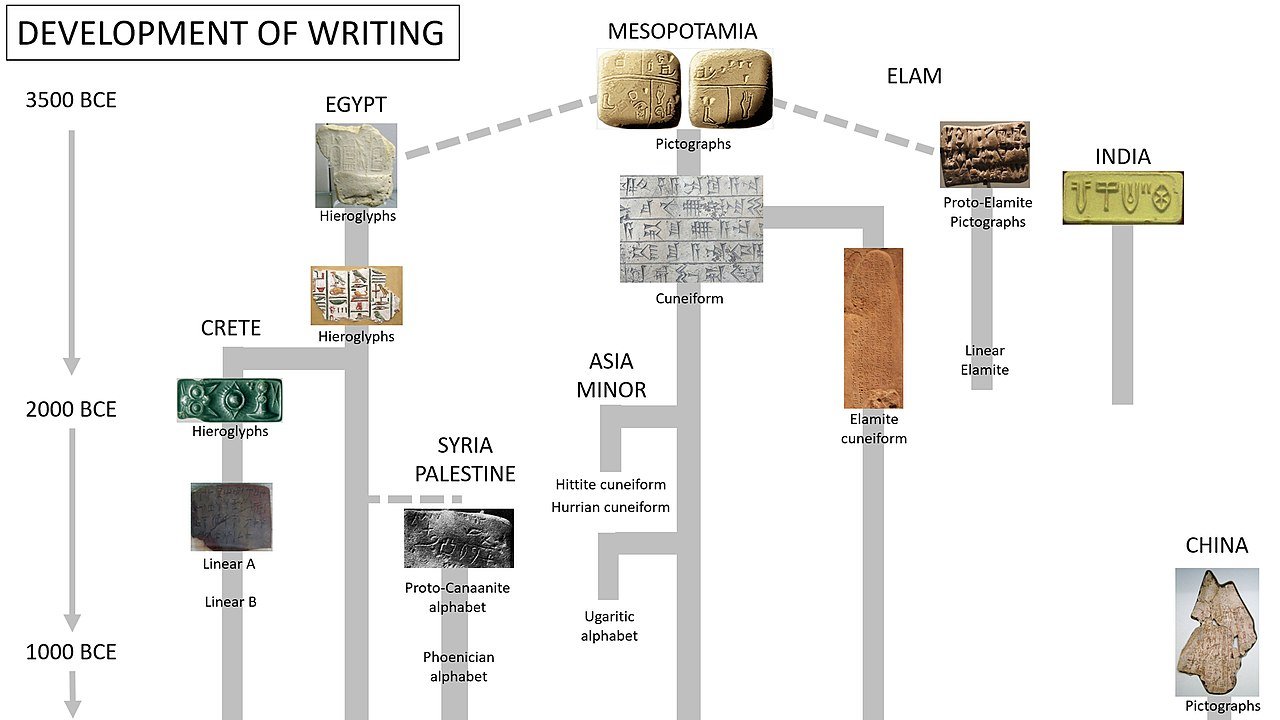

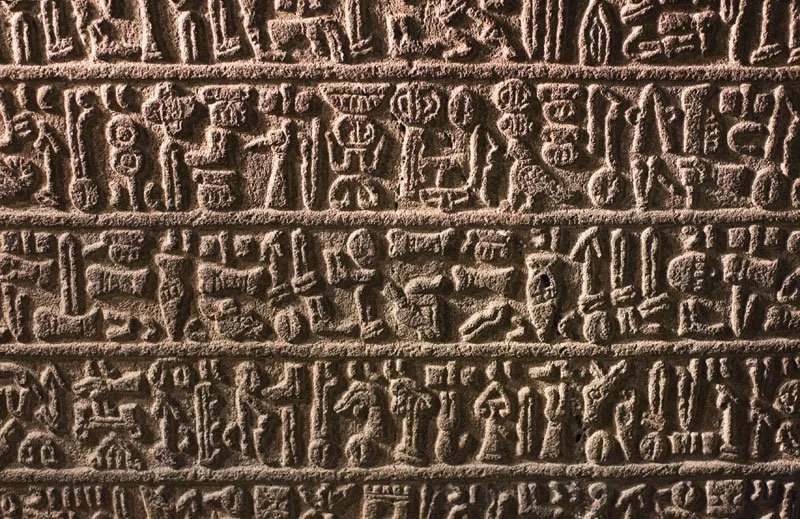

The Plimpton 322 tablet, housed within the G.A. Plimpton Collection at Columbia University, stands as a remarkable testament to the mathematical prowess of ancient Babylonians. Dating back to around 1800 BC, this clay tablet is not just a relic of antiquity but a sophisticated mathematical document that predates Greek and Indian discoveries in the field of trigonometry. Its significance lies not only in its age but also in its content, which suggests a mathematical understanding that challenges our perceptions of early human numeracy.

The Tablet’s Provenance and Historical Context

The tablet came from Senkereh, the ancient city of Larsa in southern Iraq, and George Arthur Plimpton bought it from antiquities dealer Edgar J. Banks in 1922. Its journey from a Babylonian scribe's hands to a prized item in an American university's collection reflects a century-long fascination with its mathematical tables. The script and format of Plimpton 322, typical for administrative documents from that era, indicate its creation during the Middle Babylonian period, specifically around 1822–1784 BC.

Deciphering the Mathematical Content

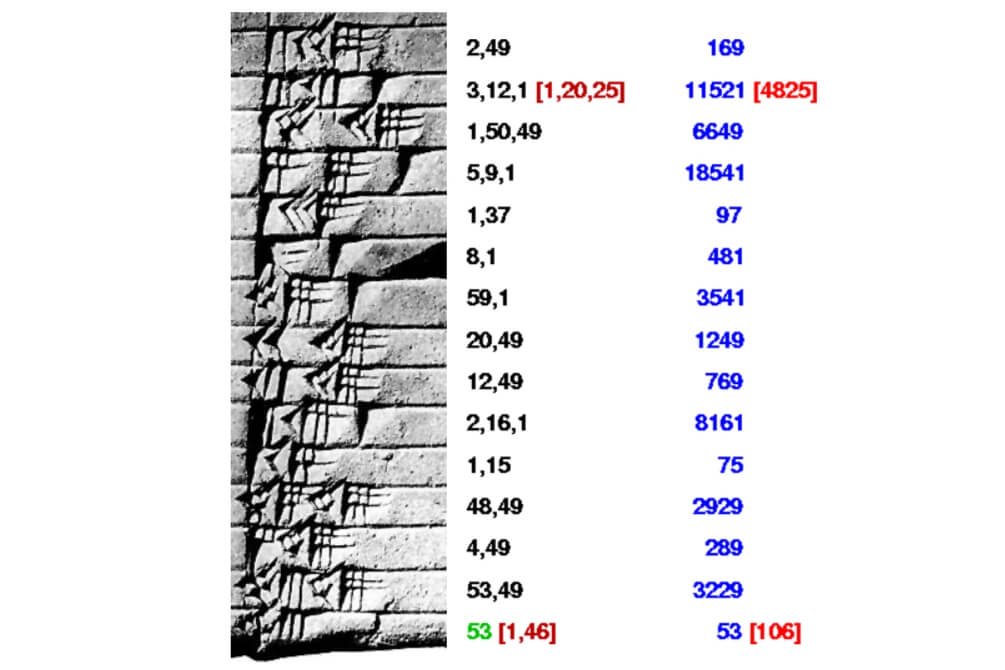

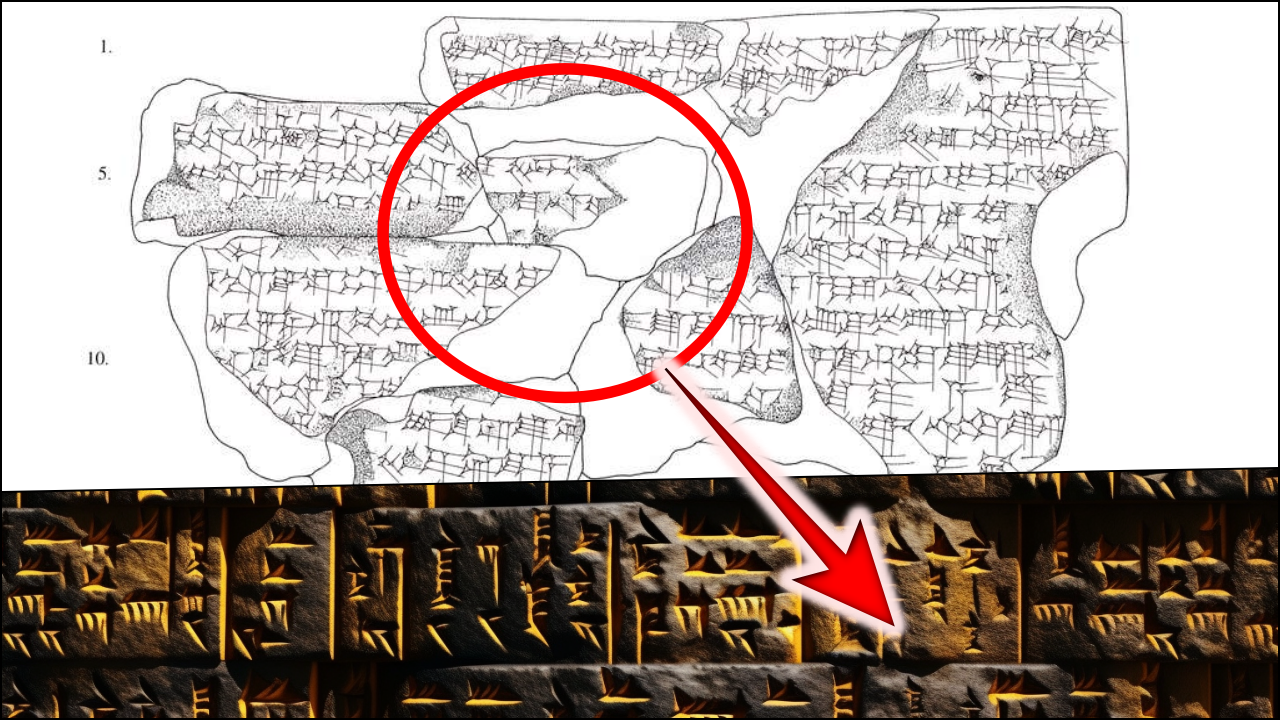

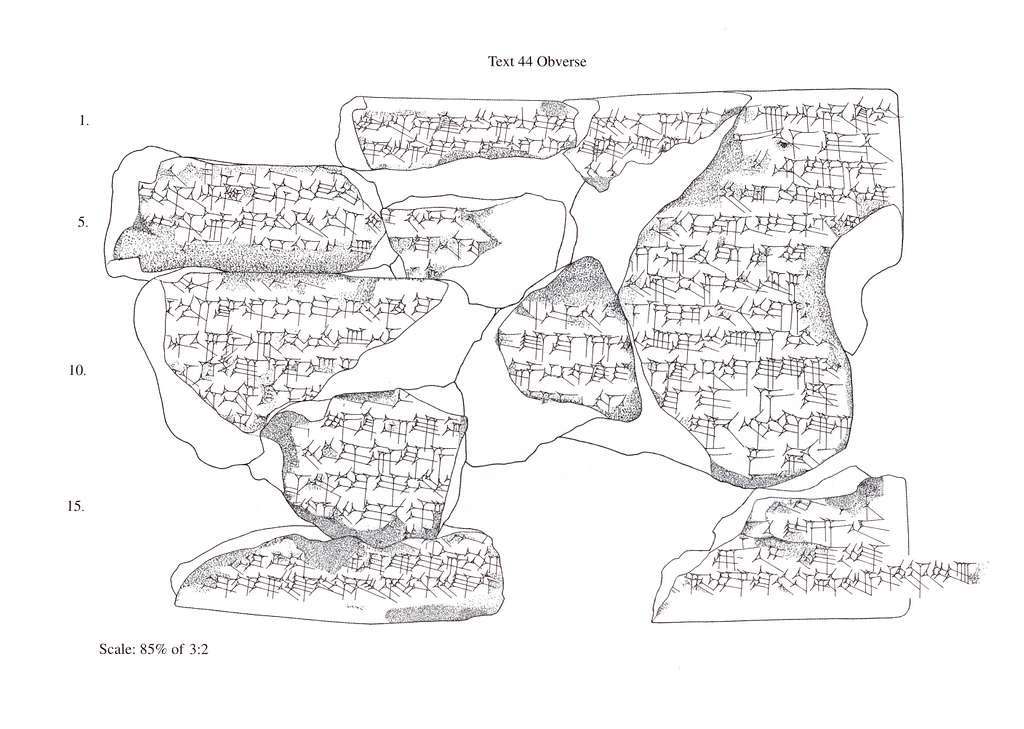

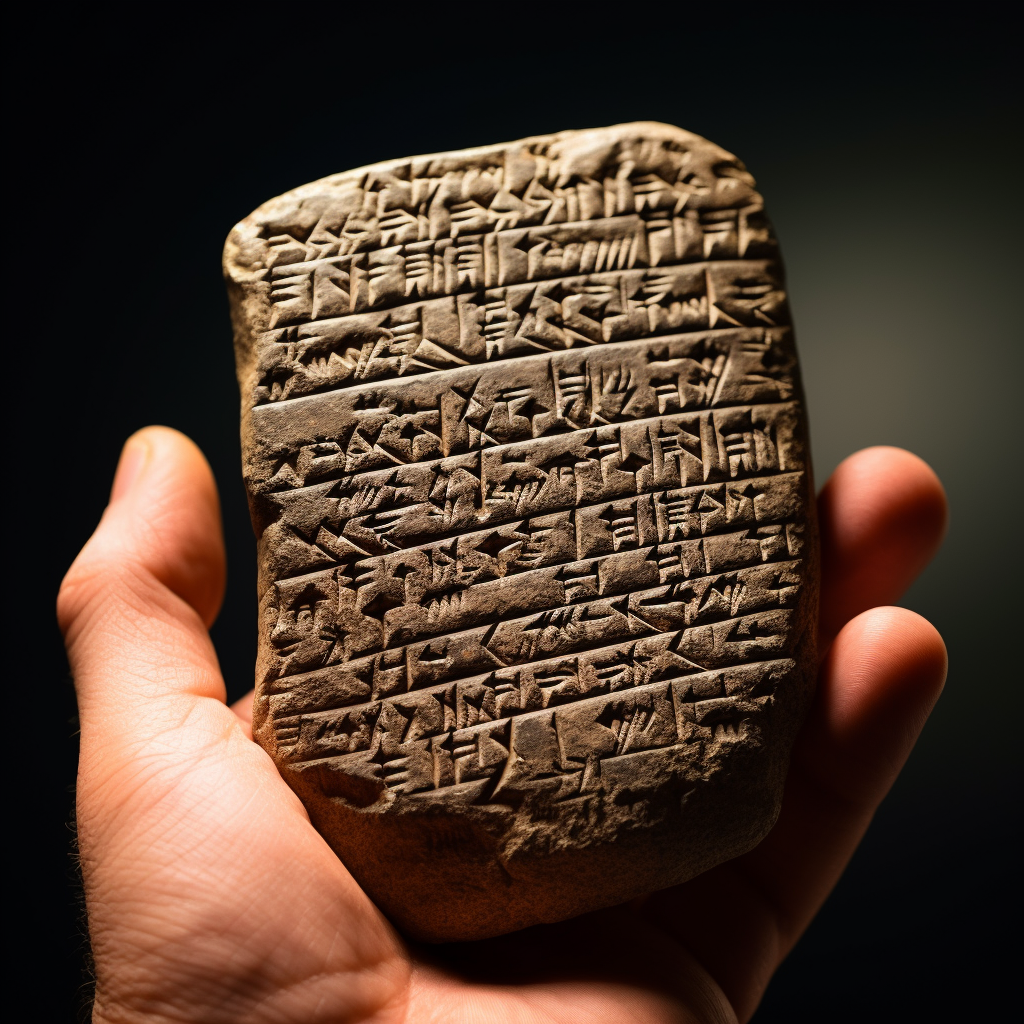

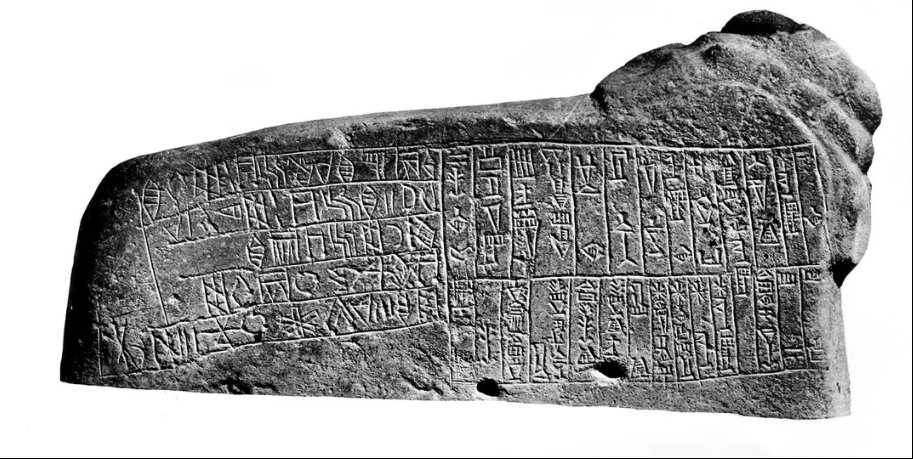

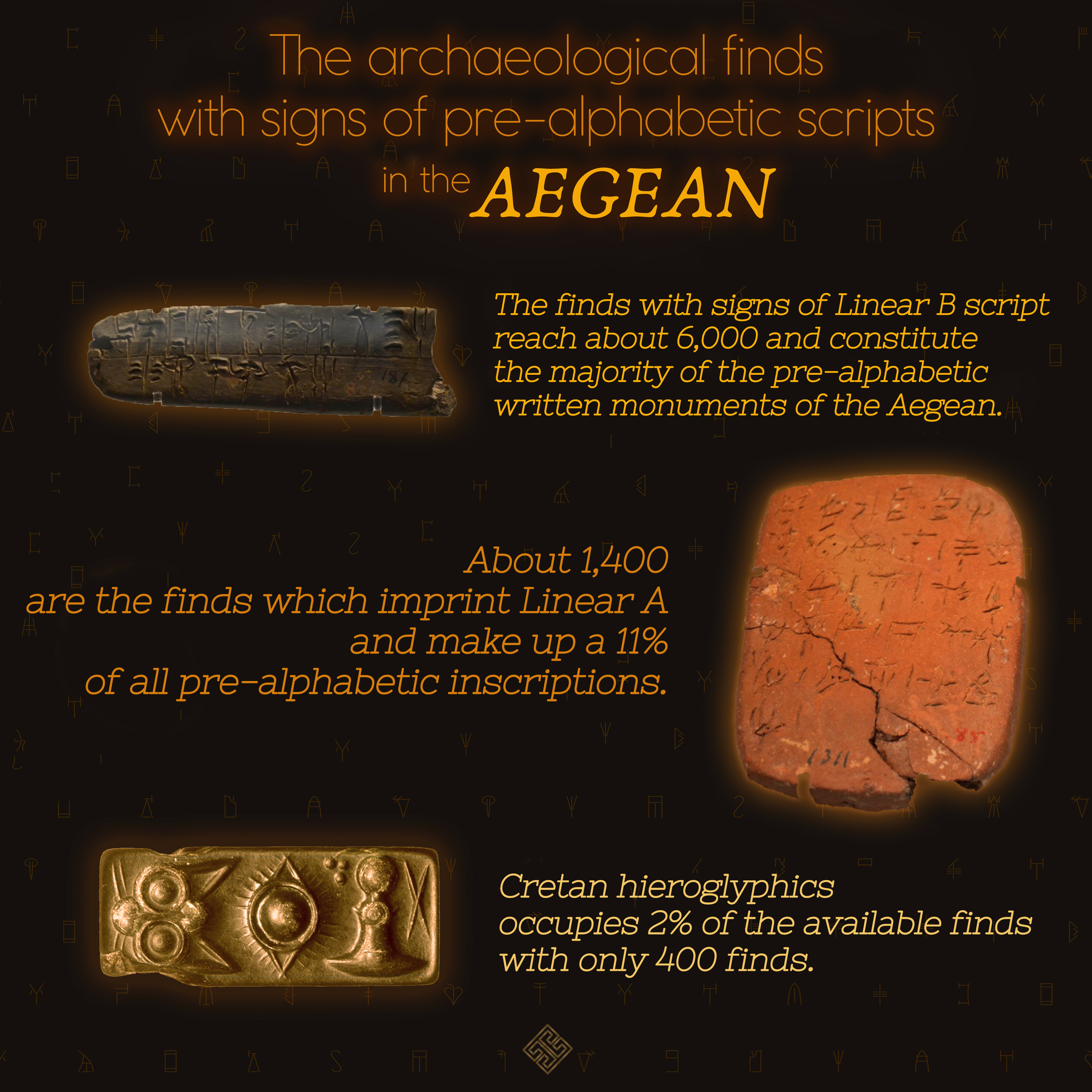

The Plimpton 322 clay tablet, with numbers written in cuneiform script

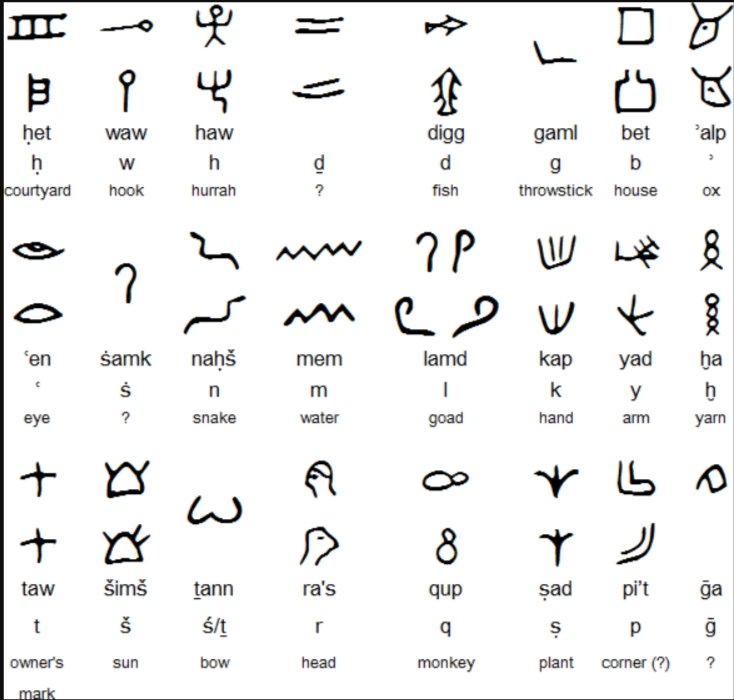

Plimpton 322 features a table in Babylonian sexagesimal notation, consisting of four columns and fifteen rows. The tablet lists two numbers from sets of what we today recognize as Pythagorean triples—sets of three positive integers a, b, and c that satisfy the equation a2 + b2 = c2. This suggests that the Babylonians had a method to systematically generate these triples, a significant mathematical achievement far preceding Pythagoras.

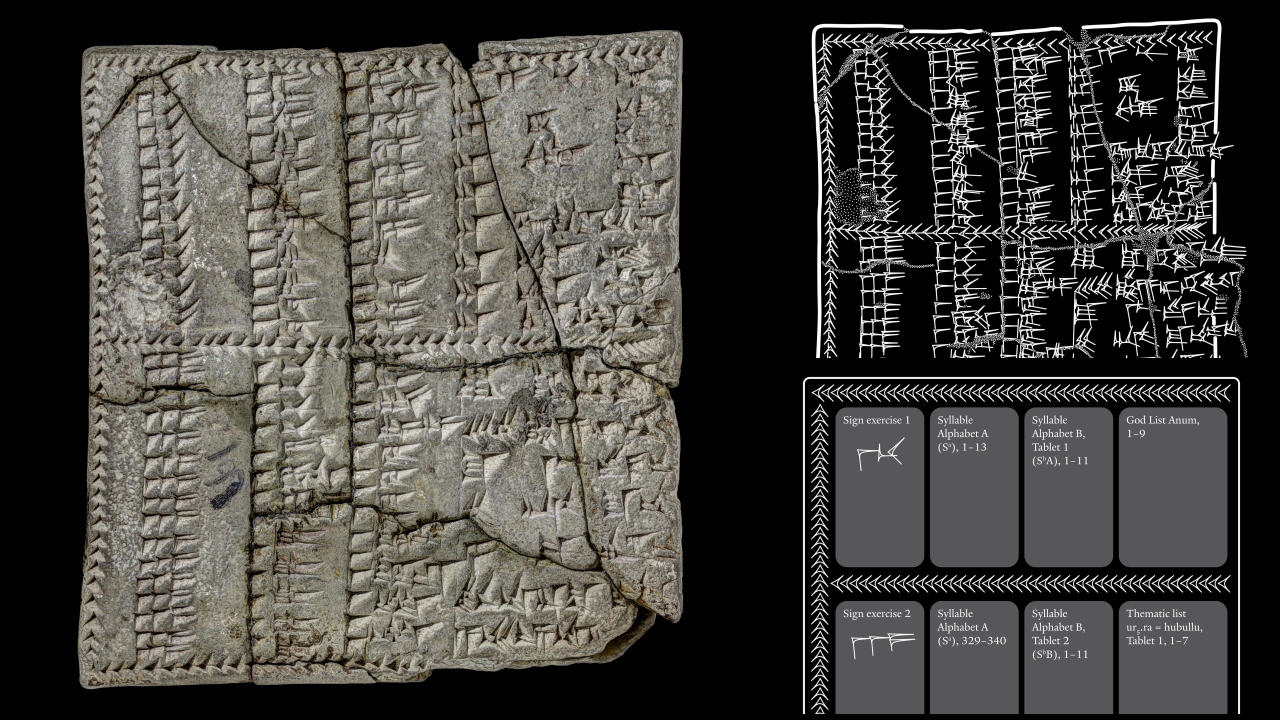

The column headings, written in Akkadian with Sumerian logograms, hint at the tablet's use in quadratic calculations. This early encounter with quadratic concepts suggests a rich mathematical tradition, with the tablet likely serving as an educational tool for training scribes rather than a purely theoretical exploration.

Scholarly Interpretations and Debates

Scholars remain divided on the exact method used to construct the numbers on the tablet. Some propose it utilizes generating pairs, a method where numbers p and q (where p>q) are chosen to form a Pythagorean triple. Others suggest a reciprocal-pair approach, where a number and its reciprocal are used to derive the triples. This latter method, detailed in recent research, aligns with other contemporary Babylonian texts that solve quadratic problems, indicating a sophisticated level of mathematical understanding.

Column three. The heading of the third column includes the word for diagonal.

Implications and Uses of Plimpton 322

The purpose of Plimpton 322 continues to be a subject of intense debate among historians of mathematics. The structured presentation of Pythagorean triples, possibly for pedagogical purposes, suggests that it served as a practical tool for teaching complex arithmetic and geometry within scribal schools. This educational use, combined with the administrative format of the tablet, paints a picture of a utilitarian approach to mathematics in Babylonian society, aimed at training scribes to handle administrative tasks effectively.

Plimpton 322 is more than just a list of numbers. It is a bridge to the past, revealing the depth of mathematical knowledge and pedagogical sophistication that existed nearly four millennia ago in Babylon. As research continues, each study adds a new layer of understanding, allowing us to appreciate the ingenuity of our ancient mathematical ancestors. The tablet not only underscores the historical continuity of mathematical thought but also highlights the universal quest for knowledge that transcends cultures and epochs. Through Plimpton 322, we connect with the Babylonian scholars of yore, whose intellectual pursuits have shaped the mathematical heritage we continue to explore today.