Stepping Beyond Traditional Theories: A Critical Response to Yamnaya Horsemanship Claims

Based on the comprehensive commentary provided in the document "About ancient horse riders: imaginary and real" by Aleksandr Valentinovich Bukalov, the following article outlines the main conclusions and discussions surrounding the early evidence of horsemanship within the Yamnaya culture, as contested by Martin Trautmann et al. This analysis reveals the complexity and controversy of interpreting early bioanthropological evidence of horsemanship.

Introduction to the Debate on Early Horsemanship

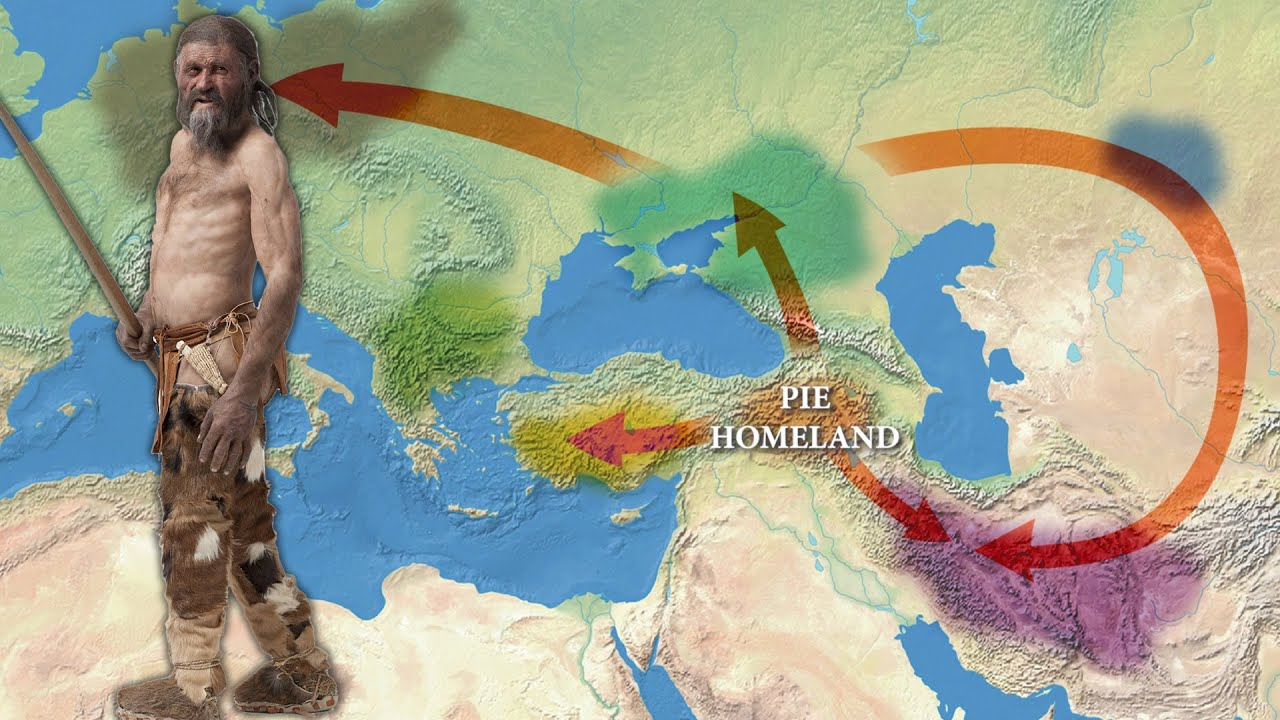

The document opens with a critical examination of the conclusions drawn by Martin Trautmann and his team regarding the early appearance of horse riding in the Yamnaya culture. The critique underscores several factors overlooked by the initial study, including the potential of riding oxen and cows before horses were domesticated and the absence of conditions conducive to horsemanship in the Yamnaya period.

Alternative Riding Possibilities and Skeletal Analysis

It presents an argument suggesting that before the domestication of horses, humans might have ridden oxen and cows. The document also mentions a bioanthropological analysis of 21 features conducted by A. Buzhilova, which did not find traces of horsemanship on the skeletons from the central region of the Yamnaya culture. This finding challenges the assertion of widespread horseback riding in this era.

Fig. 1. Map of the Yamnaya and Afanasievo overall distribution.

Sites with individuals with skeletal markers for horsemanship are marked (black circles, Yamnaya; yellow circles, graves dated to other periods) (the background map is made with Natural Earth; free vector and raster map data at naturalearthdata.com; QGIS software). 1a, Strejnicu mound I grave 3 (I/3) grave in situ (photo credit: A. Frînculeasa, Prahova County Museum of History and Archaeology).

The critique further elaborates on various aspects that question the feasibility of early horsemanship, including the physiological limitations of early horses and humans, the lack of documentary evidence of real horsemanship, and the purely utilitarian use of horses within the Yamnaya culture. These points collectively cast doubt on the conclusions made by Trautmann et al. about early horsemanship.

Additionally, the document explores the cultural and religious significance of horses in Indo-European cultures, distinguishing between the cultic aspects of horse imagery and the practical realities of horse use. This distinction highlights the complexity of interpreting archaeological and bioanthropological evidence within cultural contexts.

Skeptical View on Early Horsemanship Prevalence

The detailed statistical analysis provided in the document indicates that the evidence of morphological changes in the skeleton, which could suggest horseback riding, is minimal. This challenges the notion of widespread horsemanship in the Yamnaya culture and suggests a need for a more nuanced understanding of the evidence.

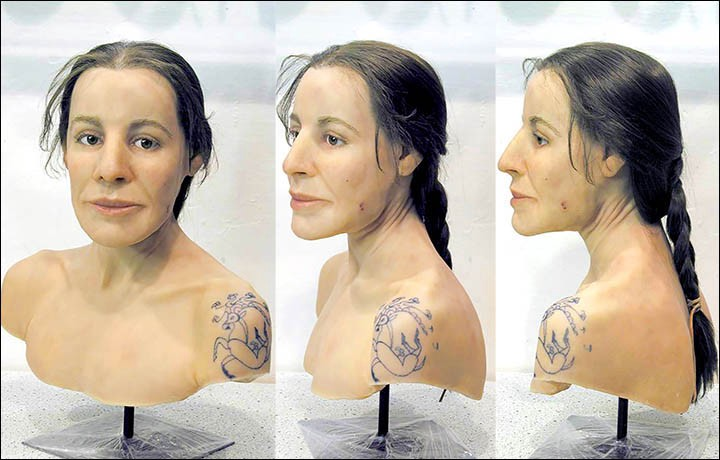

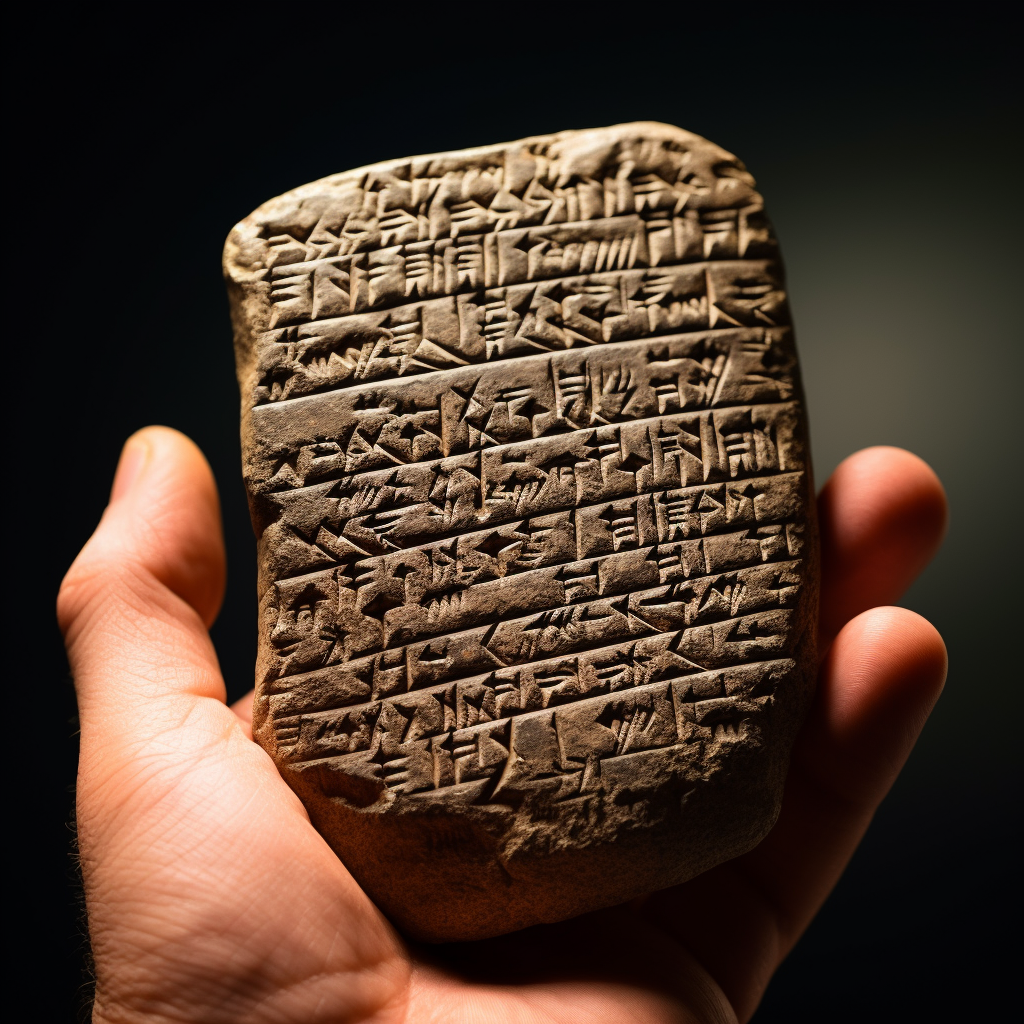

Fig. 3. The Strejnicu I/3 individual: Adaptive changes to bone morphology.

(A) The sclerotic plaque caused by femoroacetabular contact. (B) The elevated entheses of the M. adductor magnus and the thickened lateral to superior acetabular rim. (C) The entheses of M. iliacus. (D) The entheses of M. glutaeus minimus and medius. (E) The entheses of M. pectineus, M. adductor magnus, M. adductor brevis, and M. vastus lateralis (photo credit: M. Trautmann, University of Helsinki). (F) Femoral shaft cross sections in the computed tomography (CT) (see section S5).

In conclusion, the article provides a thorough critique of Martin Trautmann and his team's early horsemanship thesis. By examining alternative explanations for skeletal changes, the lack of concrete evidence for widespread horseback riding, and the cultural significance of horses, the document calls for a re-evaluation of the conclusions drawn about early horsemanship in the Yamnaya culture. This critique emphasizes the importance of considering a wide range of factors when interpreting archaeological and bioanthropological data and highlights the complexities involved in understanding the early history of human-animal relationships.

This analysis underscores the ongoing debates in the fields of archaeology and bioanthropology regarding the interpretation of evidence related to the domestication and use of animals by ancient cultures. The critique of Trautmann et al.'s conclusions serves as a reminder of the challenges faced by researchers in reconstructing the past and the need for careful consideration of all available evidence.

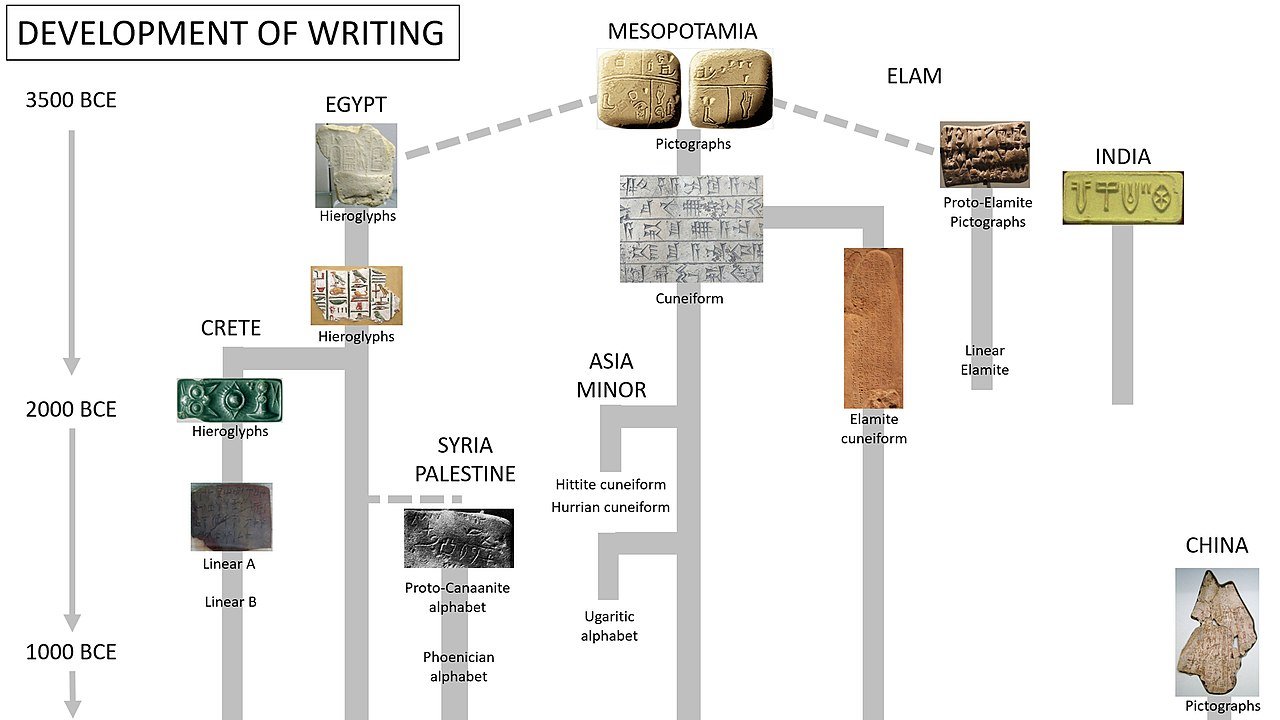

Fig. 5. Pictorial evidence of horsemanship in the Bronze Age (c. 2100 to 1200 BCE).

(A to C) Mesopotamia. (D to F) Egypt. (G to I) Aegean-Cyprus. (A) Drawing of a seal impression depicting a horse rider, Ur III period (81). (B) Baked clay plaque mold depicting a rider, Old Babylonian period [The Trustees of the British Museum; shared under a Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license; except where otherwise noted, content within this article is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license] (82). (C) Drawing of a seal imprint of Ili-pada, Middle Assyrian Empire (courtesy of F. Wiggermann, Leiden) (83). (D) Astarte on horseback: an Egyptian graffito, Nineteenth Dynasty (photo credit: S. Steiß, Berlin) (84). (E) Egyptian plaque of glazed steatite showing a horse rider trampling a fallen enemy, Nineteen Dynasty (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) (85). (F) Limestone relief with a messenger on horseback from the Horemheb tomb, Saqqara, Late Eighteenth Dynasty (Museo Civico Archeologico di Bologna) (86). (G) Clay figurine of the so-called “cavalryman” from Mycenae, early LH IIIB (courtesy of J. Kelder, Leiden) (87). (H) Horseman on an LHIIIB krater in the Allard Pierson Museum, Amsterdam (courtesy of J. Kelder, Leiden) (87). (I) Drawing of a sherd showing a horse rider from Minet el-Beida, tomb VI, LH IIIB2 (courtesy of J. Kelder, Leiden) (87).