In a prehistoric rock shelter in central Malawi, archaeologists have uncovered the earliest known evidence of an adult funeral pyre anywhere in the world.

The burned remains, dated to around 9,500 years ago, belonged to a woman estimated to have been between 18 and 60 at the time of her death. Analysis shows that her body was intentionally prepared and cremated on a large pyre that burned for many hours, as part of a planned funerary ritual. The site itself had already been used for mortuary practices for at least 8,000 years before this event.

According to a research team led by anthropologist Jessica Cerezo-Román of the University of Oklahoma, this find represents “the earliest evidence for intentional cremation in Africa and the oldest in situ adult pyre in the world.” The discovery challenges earlier assumptions about hunter-gatherer burial practices, revealing that their funerary traditions could be highly structured and elaborate.

The ritual required careful planning and considerable resources, including the collection and maintenance of enough wood to sustain a long-burning fire. The repeated use of the site over thousands of years also suggests a strong collective memory and possibly early forms of ancestor reverence among these communities.

Human concern with death has deep roots, with the oldest confirmed intentional burial dating to about 78,000 years ago, though even earlier examples attributed to other hominins remain debated. Evidence for cremation is much rarer, particularly before 7,000 years ago among hunter-gatherers. While cremated human remains discovered at Lake Mungo in Australia date to roughly 40,000 years ago, no actual pyre was preserved at that site.

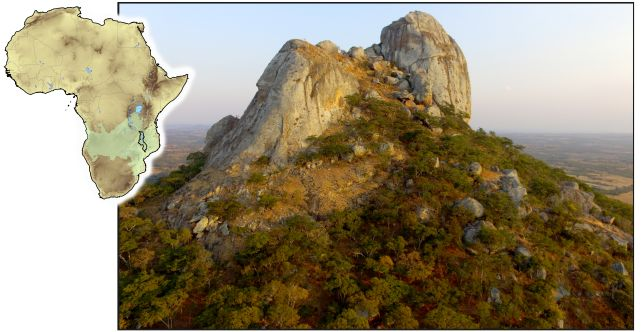

The site, HOR-1, is located in a rock shelter at the base of Mount Hora in Malawi, in eastern Africa.

Archaeologists have discovered the world’s oldest in situ adult funeral pyre in a rock shelter at HOR-1, Malawi. The charred remains, dated to 9,500 years ago, belonged to a woman between 18 and 60 years old, whose body was carefully prepared for cremation on a large pyre that burned for several hours. This site had been used for mortuary practices for at least 8,000 years, indicating a long-standing ritual tradition.

Earlier evidence of in situ pyres includes an 11,500-year-old child cremation in Alaska and, later, a 7,000-year-old example at Beisamoun in the southern Levant. At HOR-1, archaeologists have identified at least 11 individuals used in mortuary practices, but only one, designated Hora 3, shows clear evidence of pyre cremation. Parts of her skeleton – limb bones, vertebrae fragments, pelvis, and phalanges – were found within a substantial deposit of ash, providing direct insight into the complex funerary rituals practiced by these hunter-gatherers.

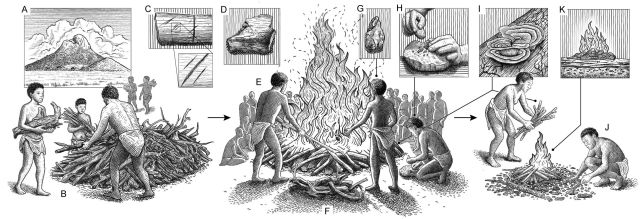

A reconstruction of the cremation ritual, for which people likely collected large amounts of wood (B) and tended to the fires (E). Evidence at the site also suggests multiple fires were relit atop the original pyre location (K) and that cranial and dental remains were possibly collected and removed (J), as none were found.

The bones show signs of long exposure to high heat, with burning and cracking evident. Cut marks indicate parts of Hora 3’s body were disarticulated before cremation, and color patterns suggest the bones were moved during the fire, likely while it was stoked. No skull or teeth were found, implying the head may have been removed prior to burning—a practice linked to mortuary rituals, social memory, and ancestral veneration.

The ash deposit suggests the pyre required at least 30 kilograms of wood, grass, and leaves to sustain a long fire, and layers of ash indicate the same location was used for fires for hundreds of years afterward. Researchers interpret this as evidence of a “persistent place,” reflecting territorial and ancestral connections.

The team concludes that the repeated construction and maintenance of fires at the site point to long-standing traditions of ritual and mortuary activity, highlighting complex community cooperation and place-making among tropical hunter-gatherers long before the onset of agriculture.