Migration into England was ongoing from the Roman period through to the Norman Conquest, with people moving from different regions at varying rates, a new study finds.

Researchers discovered that early medieval migrants came to England not only from nearby regions but also from as far afield as the Mediterranean and the Arctic Circle.

The large bioarchaeological study offers fresh insights that complement early medieval texts and ancient DNA evidence. Analysis of human tooth enamel also revealed information about past climate events, including the Late Antique Little Ice Age and the Medieval Climate Anomaly.

New Research Methods and Findings

The study, led by the Universities of Edinburgh and Cambridge, represents the first large-scale analysis combining isotopic and ancient DNA data from early medieval English cemeteries to assess population movement. The results are published in Medieval Archaeology.

The team traced population movements into England during the early medieval period, spanning from the end of Roman rule around 1600 years ago to the arrival of the Normans over 900 years ago.

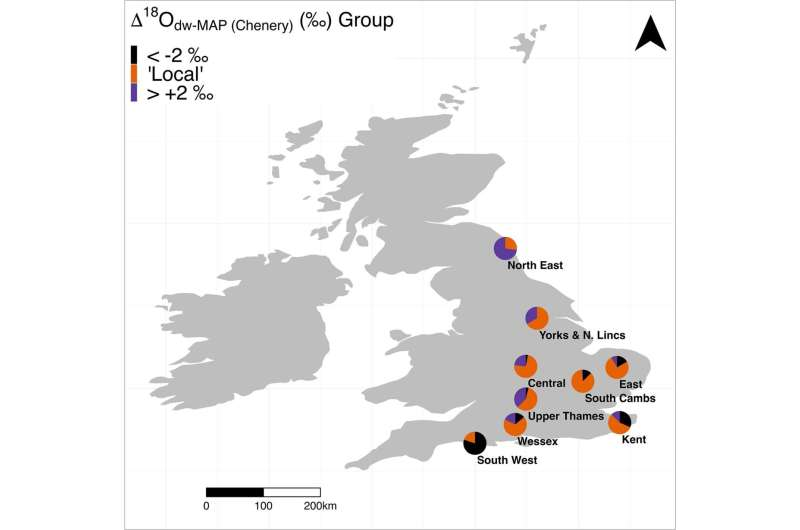

Chemical signatures in the teeth of more than 700 human skeletal remains from AD 400 to 1100 showed that migration was a persistent feature of England during this period. These findings were compared with ancient DNA from 316 individuals to distinguish between movement and ancestry.

Climate Events and Migration Patterns

Tooth enamel, which records the chemical composition of food and water consumed in early life, also captured climate fluctuations, including the Late Antique Little Ice Age of the 6th–7th centuries, as well as evidence of migrants from colder regions.

Migration was continuous rather than tied to isolated events, with a notable increase in the seventh and eighth centuries. Male migration was more pronounced overall, though there was also significant female mobility, particularly into the North East, Kent, and Wessex.

Evidence indicated migration from Wales and Ireland, as well as from northwest Europe and the Mediterranean.

Historical Sources and Broader Implications

The team compared their findings with historical sources, including Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, to see how documented mobility matched bioarchaeological evidence.

Dr. Sam Leggett of the University of Edinburgh said, “The study took a ‘big data’ approach to examine narratives around early medieval migration. We see that migration was a continuous feature rather than a series of one-off events, with communities in ongoing cross-cultural contact, linked into extensive networks that likely influenced the major socio-cultural changes of the period.”

Dr. Susanne Hakenbeck of the University of Cambridge added, “Migration to Britain occurred throughout the first millennium. We were surprised to find a spike in mobility in the 7th and 8th centuries—long after the so-called Anglo-Saxon migrations. This study also highlights that Britain was never isolated from the continent.”