For much of the past century, the arrival of the first humans in the Americas has been explained as an inland journey across the frozen landscapes of Beringia. Increasing archaeological and genetic evidence, however, is now calling that model into question. A new interdisciplinary study by Japanese and U.S. researchers suggests that the earliest ancestors of Native Americans may have originated in a coastal zone encompassing Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands—and that they likely reached the Americas by sea.

Published in Science Advances, the study argues that seafaring hunter-gatherers from Northeast Asia were central to what is often described as the final major migration of Homo sapiens.

Rethinking a Northeast Asian Homeland

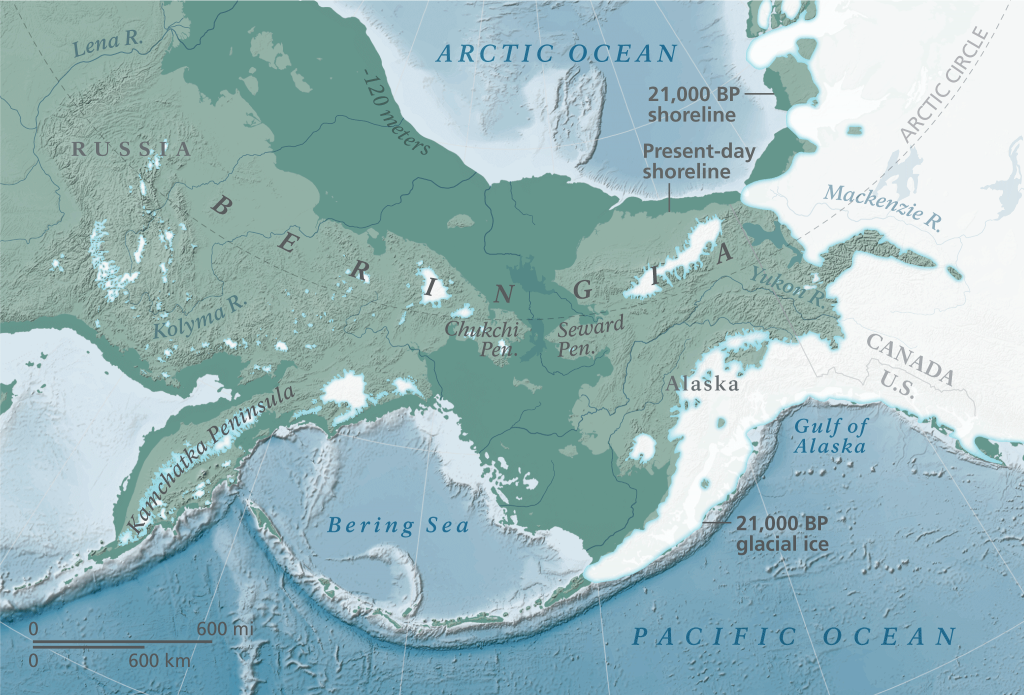

Previous paleogenomic research indicates that the population ancestral to Native Americans emerged in Northeast Asia around 25,000 years ago. Genetic evidence also points to a lengthy period of isolation—lasting roughly 4,000 to 5,000 years—marked by population decline before these groups entered the Americas sometime after 20,000 years ago. Until now, the location of this “standstill” period has remained uncertain.

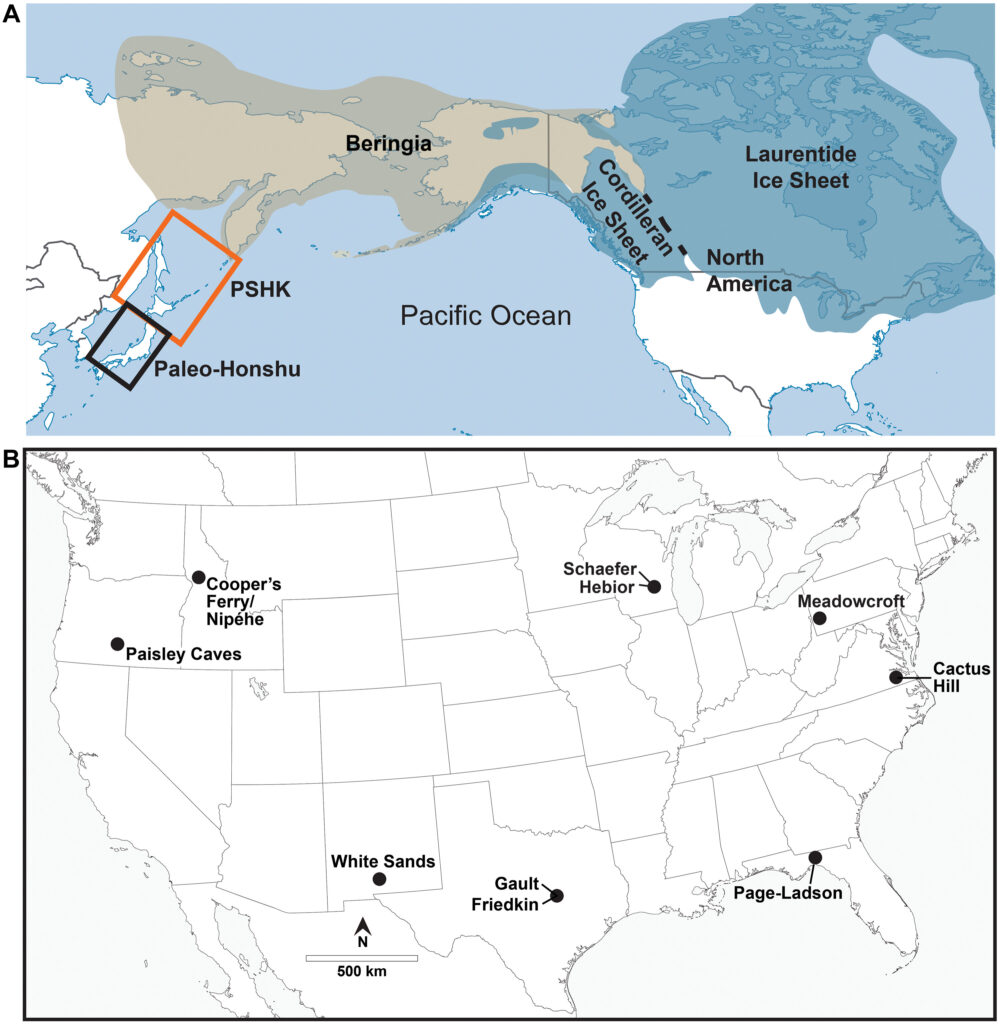

The new research proposes that this prolonged isolation most likely occurred not in inland Beringia, but in the Hokkaido–Sakhalin–Kuril (HSK) region. During the Last Glacial Maximum, this area formed a broad peninsula connected to the Asian mainland. Unlike glacial Beringia, which was a cold and resource-poor polar desert, the HSK region offered relatively stable access to both marine and land-based food sources.

Stone Tools as Evidence of Connection

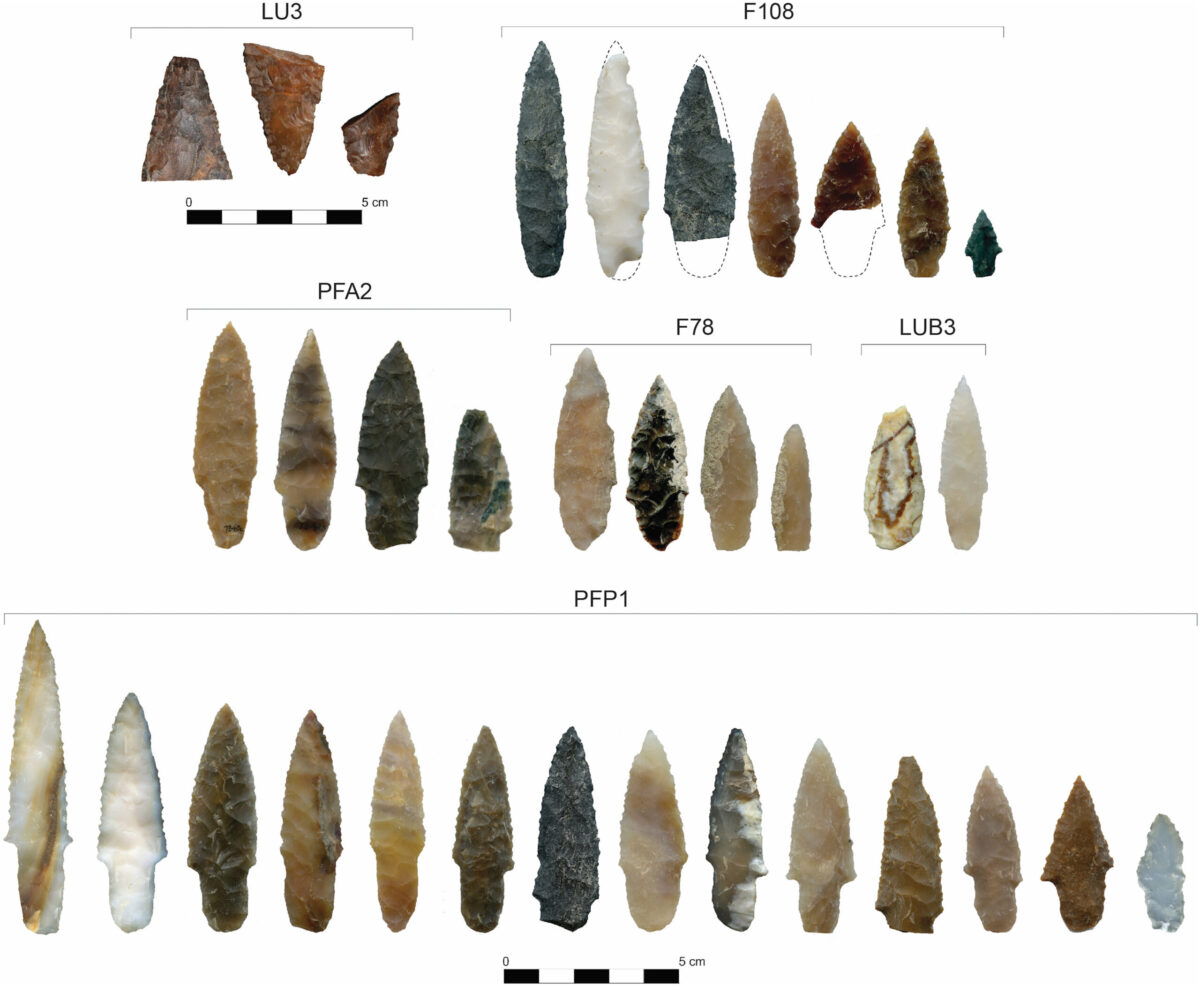

A key pillar of the study is a detailed comparison of stone tool technologies. The researchers examined lithic assemblages from ten Upper Paleolithic sites in mainland North America, dated between 18,000 and 13,500 years ago. These sites contained projectile points and blades with highly consistent characteristics, including elliptical shapes, sharp edges on both sides, and cross-sections designed for strength and penetration.

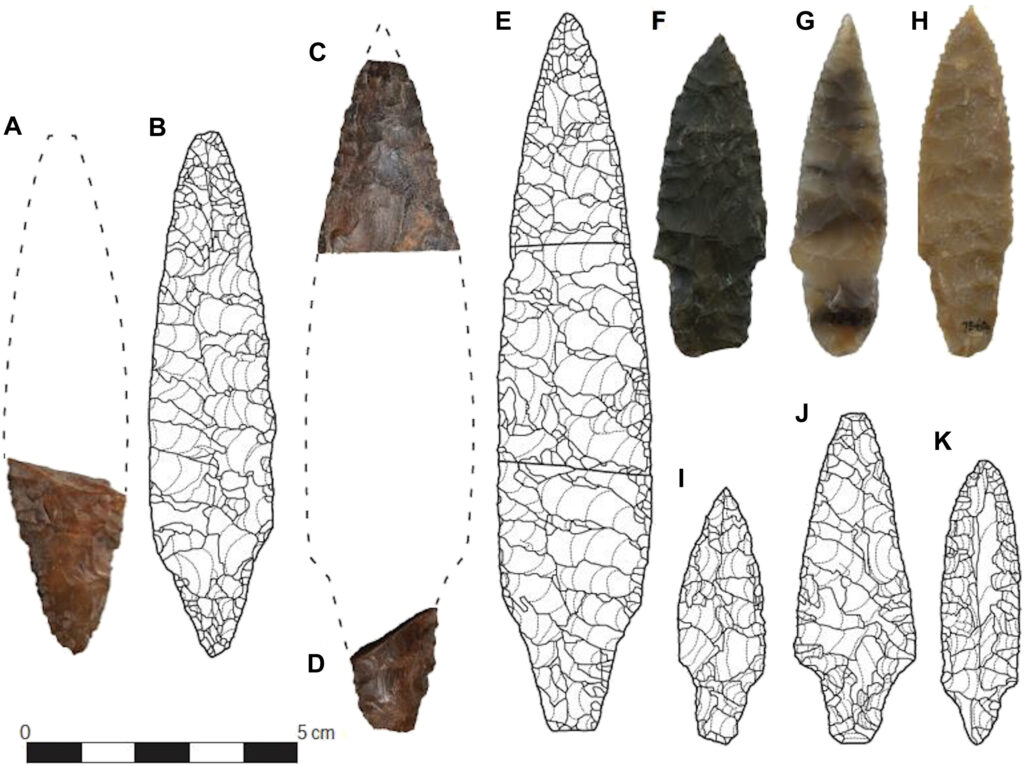

Notably, nearly identical stone tool designs have been found at sites in Hokkaido and nearby islands, some dating back to around 20,000 years ago. In contrast, similar technologies appear in Beringian archaeological contexts only after about 14,000 years ago. This timing suggests that the technological tradition spread from Northeast Asia toward the Americas, rather than originating within Beringia itself.

These projectile points were efficient and versatile, suitable for hunting land animals as well as supporting coastal subsistence. Their distribution on both sides of the North Pacific points to a shared technological heritage, likely carried by highly mobile populations with sophisticated adaptations to diverse environments.

Map showing the locations of major physiographic regions discussed in the text (A). Map showing the location of AUP sites in North America discussed in the text (B).

Why the Coast Was Crucial

At the height of the last Ice Age, between about 29,000 and 18,000 years ago, vast ice sheets blanketed much of northern North America. Any inland journey across Beringia during this time would have been extraordinarily harsh, and notably, archaeologists have found no evidence of human occupation in the region from this period.

Coastal Asia, by contrast, tells a different story. Archaeological finds from the Japanese archipelago show that humans had developed seafaring skills as early as 35,000 years ago. Sites on islands in what are now Okinawa and southern Kyushu reveal repeated open-ocean crossings, demonstrating maritime abilities long before humans reached the Americas.

Drawing on this evidence, the researchers suggest that populations from the Hokkaido–Sakhalin–Kuril region moved eastward along a Pacific coastal corridor. Traveling via shorelines, river mouths, and kelp-rich marine zones, these groups could rely on consistent food resources. This scenario closely supports the “kelp highway” hypothesis, which proposes that productive coastal ecosystems enabled long-distance migration even during the coldest glacial phases.

A Missing Chapter in Human Migration

One striking conclusion of the study is that these coastal migrants were probably not direct ancestors of modern Japanese populations. Archaeological and genetic data indicate that the Jomon people—often linked to present-day Japanese ancestry—did not arrive in Hokkaido until around 10,000 years ago.

Instead, the earlier seafaring groups may represent what researchers call a “ghost population”: a community that played a pivotal role in humanity’s spread into the Americas but later vanished or was absorbed, leaving little to no clear genetic trace in contemporary Northeast Asian populations.

Comparison of stemmed points from Japan and North America. AUP points from Cooper’s Ferry/Nipéhe LU3 (A, C, D, and F to H) and bifacial stemmed points from Hokkaido (B, E, and I to K).

Rethinking the Final Stage of Human Migration

Masami Izuho, an associate professor of archaeology involved in the study, points out that Japanese archaeological discoveries have often been interpreted only in a local context. The new research, he argues, positions these findings within a broader, global framework.

Instead of seeing the settlement of the Americas as a straightforward inland expansion by land-based hunters, the study suggests a more complex story driven by island and coastal communities with advanced maritime skills. Knowledge of boats, coastal navigation, and marine resources may have been as important as land bridges and hunting large animals.

Rintaro Ono, a maritime archaeology specialist, notes that the proposed migration—slightly before 20,000 years ago—coincides with the coldest phase of the Ice Age. Scarcity of resources, changes in animal populations, and reliance on marine ecosystems likely encouraged these coastal groups to explore new lands along the Pacific Rim.

Implications for Archaeology and Future Research

While this hypothesis does not settle the debate on the first Americans’ origins, it strongly supports the idea of a coastal migration from Northeast Asia. Future archaeological work along now-submerged coastlines, hidden beneath post-glacial seas, may provide critical evidence to test this model.

If validated, the study would reshape our understanding of the final dispersal of Homo sapiens—not as a desperate trek across icy lands, but as a deliberate expansion by skilled coastal navigators who used the Pacific coastline as a migration route.