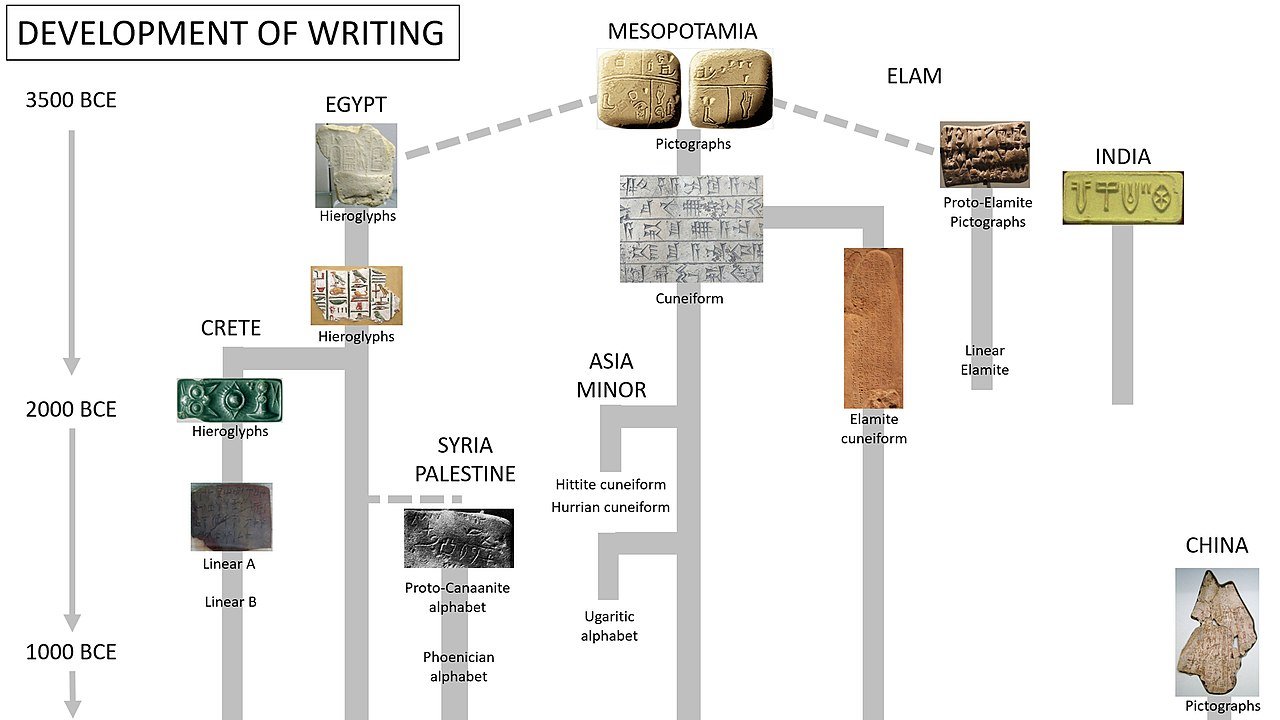

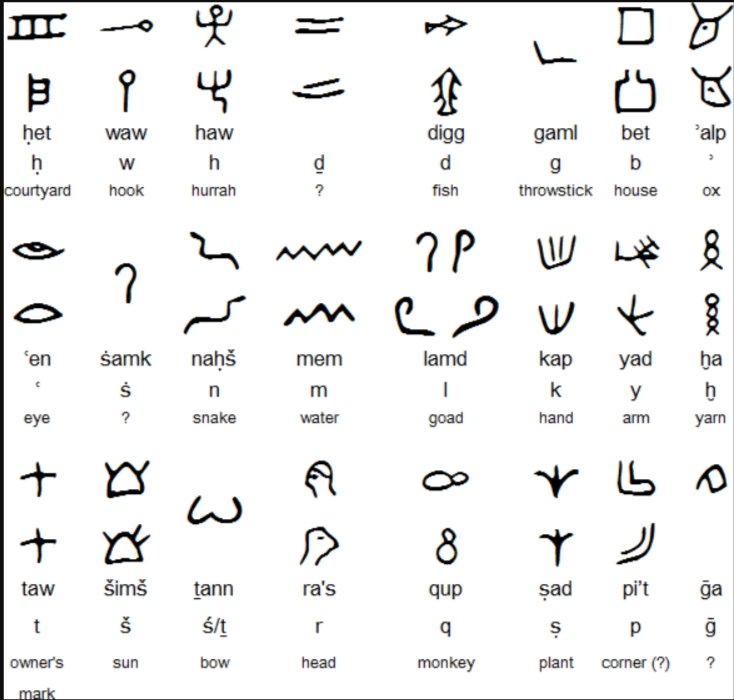

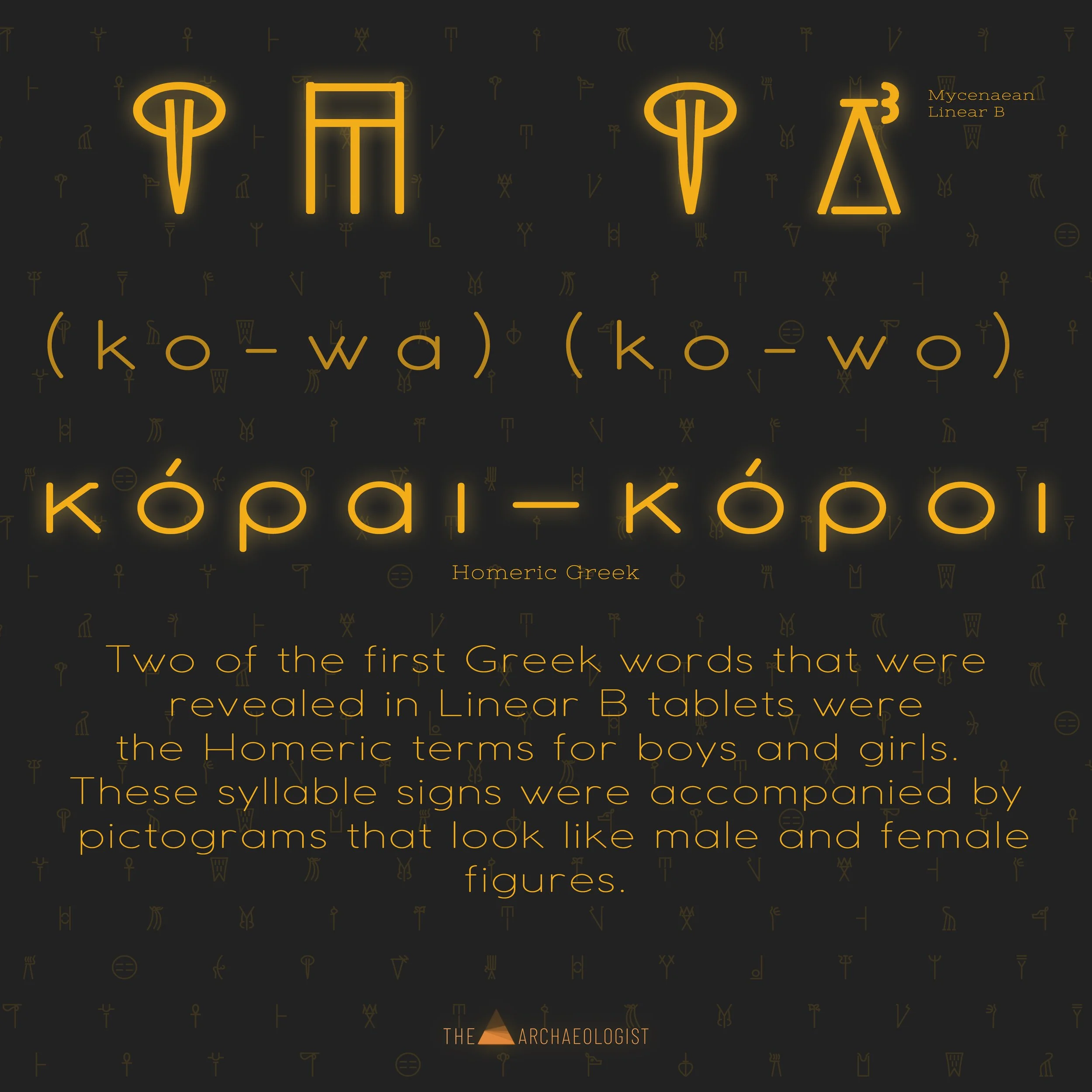

Hailing from the Mycenaean civilization of the Late Bronze Age, the Linear B script, deciphered in the mid-20th century by British cryptographer Michael Ventris, offers invaluable insights into the roots of the Greek language. As an evolved form of the Minoan Linear A script, Linear B, though syllabic in nature, played a pivotal role in administrative tasks, recording transactions, and maintaining inventory. Its legacy, firmly embedded in thousands of clay tablets, provides an extraordinary window into the socio-economic and religious dimensions of life in Mycenaean Greece around 1450 BCE.

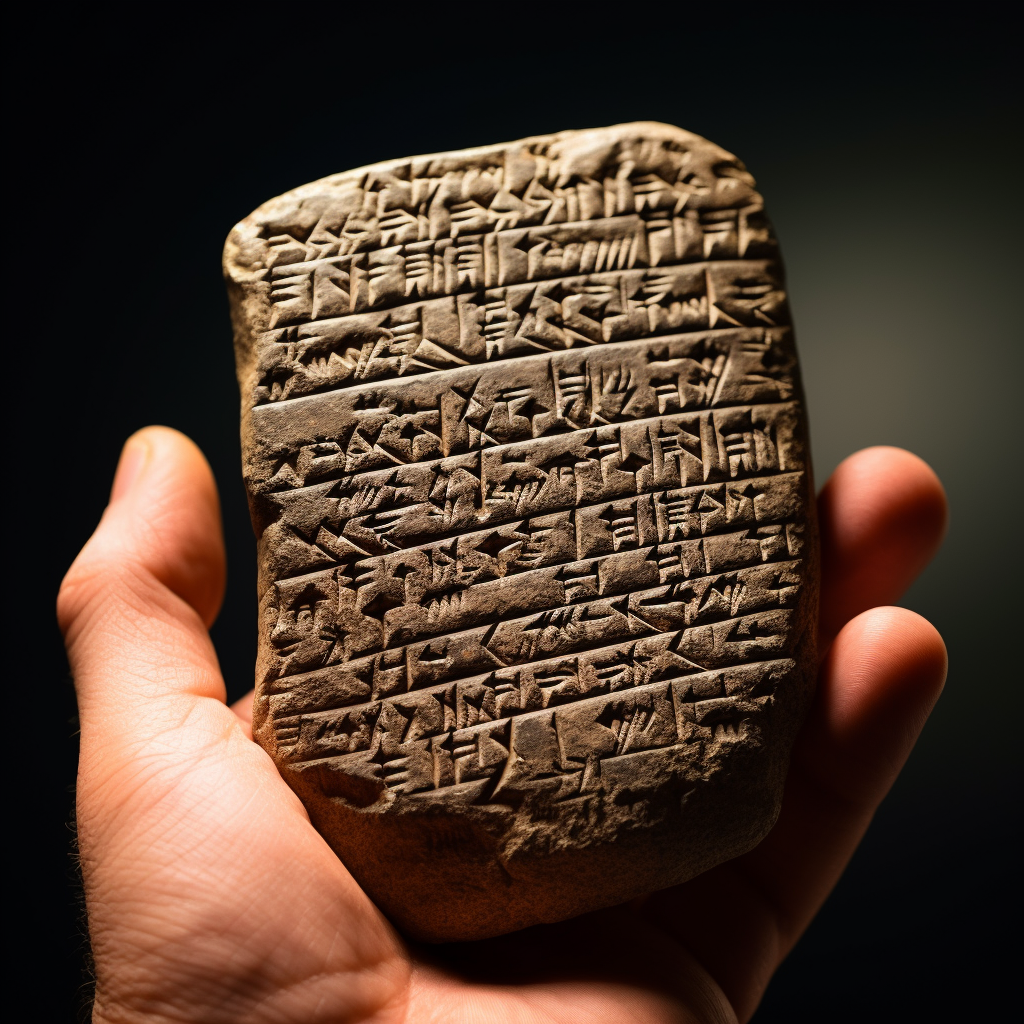

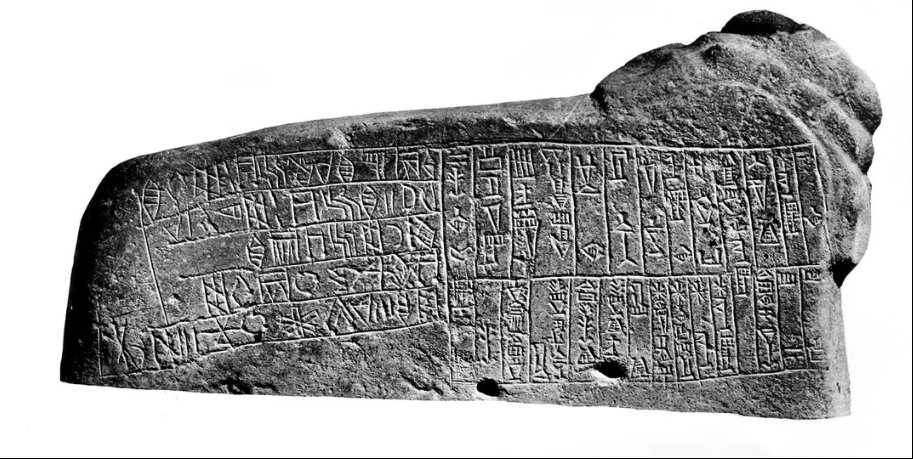

The Kafkania pebble is a tiny, rounded river stone that measures about 5 centimeters (2.0 in) in length and is etched with Linear B symbols and a double axe symbol. It was discovered on April 1, 1994, at Kafkania, about 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) north of Olympia, in an archaeological environment from the 17th century BC.

If it were authentic, it would be by far the first piece of Linear B writing to exist on the Greek mainland. Moreover, the Kafkania pebble would have needed to be there two or more millennia prior to the oldest Linear B writings. However, it is almost certainly a recent counterfeit or fraud.

Inscription

The stone has a brief inscription on it written in Linear B using eight syllabic characters that could mean a-so-na, qo-ro-qa, or qa-jo. A double-axe symbol is displayed on the reverse side. Some claim that the inscription is in Mycenean Greek; however, this assertion is still debatable. Such a singular instance of linear B writing has been hypothesized to represent, at best, an early level of Mycenaean writing at the time of genesis.

G. Owens contends that the inscription is not Mycenaean but rather Minoan in origin. The text could have been composed by a Minoan for a Mycenaean. There is no proof that Mycenaean Greek writers existed prior to the Knossos Linear B repository.

Forgery

Several specialists in Mycenaean epigraphy have expressed serious doubts about the authenticity of the inscription; indications that it is a modern forgery include:

Inscriptions on pebbles are otherwise unknown in Mycenaean and Minoan epigraphy.

The "rays" surrounding the axe have no parallels in Mycenaean or Minoan iconography.

Most of the symbols are "carefully executed" but one appears to be a "random graffito".

Its context, imbedded in a wall, is peculiar and unprecedented.

Linear B is otherwise consistently written left-to-right, but the inscription is apparently written in boustrophedon.

The writing style appears anachronistic.

It is unlikely on historical grounds that Linear B writing then existed in the northwest Peloponnese.

Finally, the pebble was apparently discovered on the morning of April Fool's Day. If it is indeed a forgery, the symbols spelling a-so-na may spell out the name Iasonas, the first name of the son of Xeni Arapojanni and Jörg Rambach, the alleged discoverers of the pebble.