"In this video, we explore the story of Leif Erikson and his journey to North America. As the son of the famous Norse explorer Erik the Red, Leif inherited a love of adventure and a desire to discover new lands. In the year 1000, he set out with a group of fellow Vikings on a journey that would lead them across the Atlantic and into the unknown.

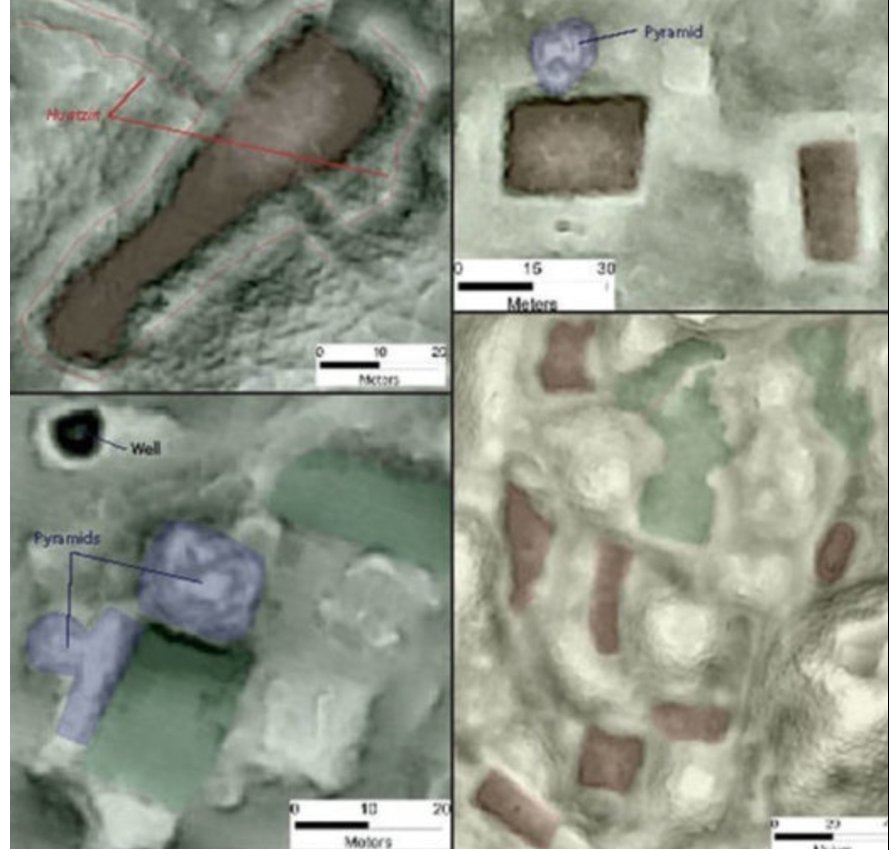

10+1 Maya Pyramids Hidden in the Yucatan Tropical Rainforests

A sizable portion of the Maya civilization was located in the Yucatan Peninsula, modern-day Guatemala, Belize, parts of the Mexican states of Tabasco and Chiapas, the western part of Honduras, and El Salvador. Today, a large number of pyramid temples and other structures, including stelae, aqueducts, and enormous paved roads, are scattered throughout the lush tropical jungle, concealed by a particular mystique.

Nowadays, Mesoamerica can be found in a variety of architectural styles. The Mayas never established a single empire and lived in autonomous city-states. As a result, different regions have different temple traits and construction techniques. But among the various Mayan towns spread throughout Mesoamerica, one can clearly see a major architectural impact from the various pre-Hispanic civilizations. The Maya erected the majority of their pyramids as temples to their gods. Some of them have sanctuaries on their summits where people perform important rituals and ceremonies.

MUNDO MAYA

Map of the most important Maya archaeological sites

The Maya culture, which dates back 5,000 years, is still visible in the ruins they left behind. The still-standing buildings serve as a tangible reminder of their affluent way of life. The intriguing history of the Mayan temples, stelae, and pottery artifacts draws tourists from all over the world. In addition to being excellent architects, the Maya were also exceptional astrologers, agronomists, and mathematicians. They also invented a remarkable writing system (Mayan hieroglyphs) as well as an astonishingly precise calendrical cycle.

Main Maya Pyramids in Yucatan Peninsula

Tikal Pyramid Temples

One of the key Mayan sites, occupied from the 6th century B.C. to the 10th century A.D., is located in the middle of the jungle, surrounded by lush vegetation. The ceremonial center is home to magnificent temples, palaces, and ramp-accessible public areas. The surrounding area is littered with the remains of homes.

Numerous buildings, carved monuments, and other artifacts bearing witness to highly developed technical, intellectual, and artistic achievements have been found. These developments date from the first settlers' arrival (800 B.C.) to the last phases of historic occupation, which occurred around the year 900. Tikal has improved our knowledge of both a remarkable past civilization and more general cultural evolution. The Great Plaza, the Lost World Complex, and the Twin Pyramid Complexes, as well as ball courts and irrigation structures, are just a few notable locations that showcase the diversity and beauty of architectural and sculptural ensembles performing ceremonial, administrative, and residential roles.

Tikal archaeological site from above.

After decades of archeological excavation, only a small portion of the thousands of ancient structures at Tikal have been excavated. The six enormous pyramids designated Temples I through VI, each of which supports a temple complex on its summit, are the most notable remaining structures. Some of these pyramids reach heights of more than 60 meters (200 feet). During the initial site survey, they were numbered in order. Each of these significant temples may have been constructed in as little as two years, according to estimates.

There are several significant pyramid temples at Tikal. Here's some information about a few of the most prominent ones:

Temple I: Also known as the Temple of the Great Jaguar, Temple I is a funerary pyramid dedicated to Jasaw Chan K'awiil, who was entombed in the structure in AD 734, the pyramid's construction having been completed for this event. This temple is approximately 47 meters high.

Temple II: Known as the Temple of the Mask, it was built around AD 700 and stands 38 meters high. Temple II is located on the west side of the Great Plaza, opposite Temple I, and it's believed that it's dedicated to the wife of Jasaw Chan K'awiil.

Temple III: The Temple of the Jaguar Priest, Temple III, stands 55 meters tall and was likely finished around AD 810. An elaborate roof comb once adorned this temple, though much of it has since collapsed.

Temple IV: The tallest pyramid in Tikal and the second tallest Maya structure in existence, Temple IV, or the Temple of the Double-Headed Serpent, stands at a whopping 70 meters tall. It was built around AD 741 by the ruler Yik'in Chan K'awiil.

Temple V: Temple V stands 57 meters high and was likely completed between AD 550 and 650. The identity of the person for whom it was built is currently unknown.

Temple VI: Also known as the Temple of the Inscriptions, it contains a lengthy hieroglyphic text important to the study of Maya history and is about 12 meters high.

Each of these temples has its own unique architectural and historical features, and all of them contribute to our understanding of the ancient Maya civilization.

2. El Mirador/La Danta

La Danta Pyramid

El Mirador is another significant ancient Maya archaeological site located in the northern Petén region of Guatemala, like Tikal. It's particularly well-known for its large structures, including the massive La Danta complex.

La Danta is one of the world's largest pyramids by volume, although it doesn't reach the heights of the Egyptian pyramids. La Danta measures approximately 72 meters (236 feet) high. However, because it's built on a platform that's already elevated, its top is some 230 meters (754 feet) above the level of the plaza.

The base of the La Danta complex covers over 2.1 hectares (5.2 acres). When considering the total volume of the complex, including the underlying and adjacent platforms, it's one of the most massive ancient structures in the world. Some estimates put its total volume at over 2.8 million cubic meters.

Los monos complex

The structure of La Danta is made of cut stone, covered in stucco, and its platforms are supported by retaining walls of rock fill. The pyramid is part of a sprawling complex with multiple plazas, terraces, and smaller buildings. It's a typical example of the triadic style, popular in the Preclassic Maya period, which features a central structure flanked by two smaller inward-facing buildings, all mounted upon a single basal platform.

El Mirador flourished during the Late Preclassic period (around 300 BC to AD 100) and was one of the largest cities of ancient Maya civilization during this time. Although it had largely fallen into obscurity by the time of the Classic period (AD 250–900), when Tikal rose to prominence, it was a significant hub of culture, commerce, and local politics.

The site was rediscovered in 1926 and named El Mirador (The Lookout) because of its high altitude relative to the surrounding terrain. It's been the focus of extensive archaeological investigation, and efforts have been made to make the site more accessible for tourism. However, its remote jungle location makes access challenging, and it remains less well-known and less visited than some other Maya sites.

3. calakmul

Calakmul is another significant Maya archaeological site, located in the Mexican state of Campeche, deep in the jungles of the greater Petén Basin region. It is situated within the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, close to the Guatemalan border. Calakmul was one of the largest and most powerful ancient cities in Maya history.

Structure II

Discovered under a late-period temple are some of the most stunning murals ever seen in the Maya world. There are at least eight Sacbe (white stone roads) that have been identified in the archeological zone.

The city was first established around 500 BC and reached its peak during the Classic Period of the Maya civilization, from AD 250 to 900. At its height, Calakmul is believed to have had a population of over 50,000 people, and its influence would have extended to many smaller nearby communities.

Calakmul was established atop a small natural plateau surrounded by a savannah, deep within the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, and about 22 miles (35 kilometers) from the Guatemalan border. A system of canals and aguades supplied water. With a population of about 50,000 and over a million people under its political influence, it was one of the biggest and most powerful city-states in the Maya world.

Unlike many other Maya cities, Calakmul was never completely abandoned. While its political power waned at the end of the Classic period, it remained a place of activity and habitation up until the time of the Spanish conquest.

Here are a few key points about Calakmul:

Architecture and Layout

Calakmul is known for its great plaza and over 6,750 ancient structures, the largest of which is the great pyramid at the site, Structure 2. This pyramid is over 45 meters (148 feet) high, making it one of the tallest of the Maya pyramids. There are two tombs inside the pyramid with murals that are of great significance to Maya archaeologists.

The city is divided into roughly two halves by a series of reservoirs. The northern half appears to be the older part of the city, while the southern half, built later, is more grid-like in its layout.

Stelae and Monuments

Calakmul was a significant center of power, as evidenced by the large number of stelae found at the site. Stelae are large stone slabs, often carved with images and text. Calakmul has over 120 of these stelae, many of which portray the city's rulers and record their accomplishments.

The city of Calakmul is made up of a number of plaza groups centered on the Central/Grand Plaza and aligned with the four cardinal directions. These buildings are part of the Central Plaza Group: II, IV, V, VI, and VII. The enormous pyramid or temple known as Structure II at Calakmul is unquestionably the site's most magnificent building. It is located on the plaza's south side. It took many centuries and multiple expansions for this tower to reach its final height of about 150 feet (50 meters), making it the tallest and largest building in the Maya civilization. The diameter of its base is more than 400 feet (130 meters).

Structure VI, Structure VII, and Structure IV are all situated on the plaza's west, north, and east sides, respectively. The "E Group" is made up of structures IV and VI, which are assumed to have served as astronomical markers for the equinoxes and solstices.

Temple I

Structure Is a solitary structure that is situated south of the Central/Great Plaza. At a height of 130 feet, it is the second-highest pyramid in the area (40 meters). The pyramid is supported on a platform that extends 328 feet (100 meters) on each side.

The ball court lies to the north of Structure XIII. It is a 26-foot-tall, four-story, pyramid-shaped platform (8 meters). The platform foundation is 141 feet (43 meters). A two-story building is located atop the pyramid's peak and is reached by a central stairway. The edifice was built in the eighth century, according to a number of stelae that are present here.

The site of Calakmul was rediscovered in 1931, and archaeological work has been ongoing since the 1980s. In 2002, it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site, both for its cultural significance and because of its location within the protected Calakmul Biosphere Reserve.

Visiting Calakmul today involves a fairly lengthy trip into the jungle, but visitors are rewarded with impressive ruins and the rich biodiversity of the surrounding reserve.

4. Dzibanche - Kinichná

Kinichna acropolis

North of the Kohunlich ruins is a significant archaeological area called Dzibanche. The name, which in Yucatec Maya means "writing on wood," was given to a wooden support lintel covered in glyphs that was discovered in one of the temples. The site spans 7.7 square miles (20 square kilometers) in size, although the central region is significantly smaller and more accessible. 40 000 people are thought to have lived there at its peak population.

The site was occupied from around 200 BC to AD 900, flourishing during the Late Classic period (600–900 AD).

Xibalba plaza with temple of the owl (right) and temple of the cormorants (left).

The site features several plazas and a number of large temple pyramids. The most impressive among these is the Temple of the Captives, which gets its name from the various carved figures found in the temple that appear to be bound captives. Another significant structure is the Temple of the Lintels, which is named for its above-mentioned inscribed wooden lintels, an unusual feature in Maya architecture.

The site is home to four major groups that are dispersed over a vast area. Dzibanche, Kinichna, Tutil, and Lamay are the names of the groups. The Lamay Group can be viewed on the left side of the road on the approach to Dzibanche, although only Dzibanche and Kinichna are accessible to the general public. Causeways made of elevated white stone known as sacbeob connect these groups. The most significant municipal and ceremonial buildings at the site are found in Dzibanche.

The main building, known as the Temple of the Cormorants, is situated on the east side. Its Teotihuacan talud-tablero architecture makes it the tallest pyramid at the location. This edifice has several friezes attached to it. The base of this multi-tiered pyramid contains a masonry-built superstructure. The plaza level is reached by an outstanding central staircase that ascends to the summit temple. The multi-chambered temple's three entrances are divided between two pillars.

Kinichna acropolis

The Xibalba Plaza may be seen from the back of the Temple of the Cormorants, which is situated next to it. It can be reached by stairs on the building's northwest side. The focal point of this plaza complex is the Temple of the Owl, Structure I. It is a massive pyramid with Peten-style construction. A wide, central staircase ascends to a temple with numerous chambers. Via interior stairs, a tomb of a powerful woman from the late 5th century was discovered here.

Kinichna is located close to Dzibanche and is often visited in conjunction with it. Its most notable structure is a massive pyramid, believed to have been a royal residential complex. This pyramid, which visitors can climb, offers views over the surrounding jungle.

The name "Kinichna" means "House of the Sun" in Mayan. This site dates to the same period as Dzibanche, and there may have been close connections between the two cities.

The Kinichna Group is situated along a side road and behind the visitor center. The main building is a massive platform base with a three-level acropolis within it. It is a striking early classical building surrounded by trees in a tiny plaza with low platforms in front of it. There were two royal graves inside the building. A stucco Kin/Sun sign on the back of this building serves as the group's moniker. It was worth the quick drive.

The general public cannot access the Lamay group. Its main body is supported by a tall platform foundation. To the south of Dzibanche is where you'll find the Tutil Group. The Temple of the Paired Pilasters, the principal building, exemplifies peculiar Rio Bec-style architecture.

Archaeological excavation and restoration work at Dzibanche and Kinichna started in the late 20th century, and both sites have been opened to tourism. However, due to their remote locations in the dense jungle of Quintana Roo, they are less frequently visited than some of the more famous sites in Yucatan, such as Tulum or Chichen Itza. This can make a visit to Dzibanche and Kinichna a unique experience, offering a sense of the grandeur and mystery of the ancient Maya civilization without the crowds found at more accessible sites.

5. KOCHUNLICH

Kohunlich is a large archaeological site of the ancient Maya civilization, located in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, in the Yucatán Peninsula. The city was first settled around 200 BC, but most of the buildings now visible were built in the Early Classic Period, from about AD 250 to 600.

The site was originally named by archaeologists after the nearby modern town of X-làabch'e'en, which means "old water" in the Maya language. The current name, Kohunlich, is a corruption of the English name "Cohoon Ridge," referring to the cohoon palm, a local tree species.

Kohunlich covers about 21 acres and surrounds a central plaza. The city's buildings were constructed from limestone, and many of them are quite well preserved. One of the most famous structures at the site is the Temple of the Masks, which gets its name from the large stucco masks that decorate its facade. These masks, each over 1.5 meters high, are remarkably well preserved, offering a unique insight into ancient Maya art and symbolism.

Other significant structures at Kohunlich include the Palace of the Stelae, the Plaza of the Acropolis, and the Plaza of the Stepped Pyramids. The city also has a number of residential buildings, showing that it was once a thriving urban center.

Kohunlich is particularly notable for its well-preserved residential area and its advanced system of urban design and water management. The city includes a number of large platforms that were once topped by residential buildings, indicating that it was home to a substantial population. The city's inhabitants also created an intricate system of channels and cisterns to control the flow of water and conserve it during the dry season.

Present Status: Kohunlich is relatively off the beaten path compared to more famous sites like Chichen Itza or Tulum, but it's a notable destination for those interested in Maya archaeology and history. The site is situated in a lush jungle setting, which adds to its appeal, and the preservation of its structures offers a vivid glimpse into the ancient Maya civilization.

The exact peak and decline periods of Kohunlich are still not definitively known, and the site continues to be an important focus of ongoing archaeological research.

6. COBA PYRAMIDS

Nohoch Mul Pyramid, Cobá

Coba is an ancient Mayan city located in Quintana Roo state on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. It was a major urban center during the Classic Period of Mayan civilization, which spanned from about 250 to 900 AD. At its peak, Coba may have had a population of over 50,000 people.

Key structures and features in Coba:

Nohoch Mul Pyramid: This is the tallest pyramid in Coba and one of the tallest in the Yucatán Peninsula, standing at about 42 meters (137 feet) high. It is also known as the "Great Pyramid.". A steep 120-step climb to the top of Nohoch Mul provides an expansive view of the surrounding jungle. Unlike many ancient sites in Mexico, as of my knowledge, as of September 2021, visitors are still allowed to climb this pyramid. However, rules can change, so it's best to check the current situation before planning a visit.

xai'be pyramid

Other Structures: The city of Coba includes several large pyramid structures and a variety of other buildings. There's the Church (La Iglesia), the second-tallest structure in Coba; the Ball Court (Juego de Pelota), where Mayans used to play a ceremonial ball game; and the Paintings Group (Grupo de las Pinturas), named for the traces of colored murals found there. There's also a series of raised stone paths known as sacbeob (plural of sacbe) that connect the central areas of the city to outlying structures and nearby cities.

Sacbeob (White Roads): One of the distinctive features of Coba is its network of sacbeob, or "white roads.". These raised causeways were built of stone and covered in white plaster, and they connected the various parts of the city and linked Coba to other Mayan sites in the region. The longest sacbe in Coba extends over 100 kilometers (62 miles) to the site of Yaxuna. These sacbeobs are a testament to the engineering skills of the ancient Maya.

Stelae: Coba is known for its large stone slabs, known as stelae, which are carved with glyphs and images. These stelae were often used to commemorate significant events or the lives of important individuals.

In 1973, Cobá's archeological site was finally made accessible to the general public. Although there are thought to be 6,000 structures there, only three communities are accessible to the general public. Coba is not a single site like Chichen Itza, Ek Balam, or even Tulum; rather, it is a huge collection of monuments linked by more than 16 Mayan ceremonial "white roads" (sacbéob), all of which are related to the central pyramid.

Nohoch Mul Pyramid, Cobá

The group that is furthest away from the entryway is the Nohoch Group. The reason it is featured here first is because this group includes Ixmoja, the highest pyramid at Coba, which is around 138 feet (42 meters) tall. The highest pyramid in northern Yucatan is reached after a dizzying 112 stairs (others claim 130).

La Iglesia, or the Church, is the most significant of the buildings that have been unearthed and consolidated in the Acropolis. La Iglesia, Structure B-1, which has a height of over 72 feet (24 meters) and was constructed and added upon over several centuries beginning in the Early Classic, is the second tallest pyramid at the location. It has nine tiers and a tiny post-classic temple on top. It is located at the rear of Courtyard A, an open courtyard that faces west and overlooks the plaza and Lake Coba. Regrettably, climbing the pyramid is no longer possible.

Muuch'il Boonilo ob (Painting Complex) in Coba.

The Paintings Group, which is predominately Post-Classic (1100–1450 A.D.), includes East Coast-style buildings like those in Tulum, Mayapan, and Chichen Itza. It has many buildings, the greatest of which is the Temple of the Paintings, Structure 1, which is gathered around a single plaza. It is a pyramidal building on the east side of the plaza that is topped by a tiny temple that has remnants of painted paintings. It stands 26 feet (8 meters) tall. The temple has a single room with two entryways on the west side serving as its main access points. On the north and south sides, there are other single entryways that can be observed.

A sizable plaza that is a component of the D Group is located just beyond the Ball Court. Several sacbeobs enter and go from this area. The main building, called Xai'be, is located at the east end of the plaza and means "crossroads" in Yucatec Maya. This four-tiered, conical-shaped structure with two medial moldings has been tastefully repaired. On the west side of the building, there is a staircase. A covered stela is situated in front of the staircase. It is incorrect to call this building an observatory.

Today, Coba is a popular tourist destination. Its remote location and extensive ruins make it a great spot for those interested in Mayan history and culture. The site is surrounded by two large lagoons, and the city's ruins are interspersed with dense jungle, adding to its beauty. The site also has a visitor center, which offers more information about the city and its history.

Coba remains an active site for archaeological research, with many structures still partially unexcavated or undiscovered, leaving much about the site and its history to be learned.

7. cerros ruins

Cerros is a significant archaeological site associated with the ancient Maya civilization, located in northern Belize. Situated in Corozal Bay, it's notable for its pyramids, some of the earliest identified in the Maya world, which makes it a key site for understanding the transition from the Preclassic Period (2000 BC to AD 250) to the Classic Period (AD 250 to 900) of Maya history.

Historical Significance

Cerros was inhabited from about 400 BC to AD 400. The city reached its peak during the Late Preclassic Period, from around 50 BC to AD 150, during which time its population increased significantly and many of its most notable buildings were constructed.

This was a time of major social and political change in the Maya world. It is believed that a new religious ideology related to the worship of the Maya maize god was spreading throughout the region. The leaders of Cerros appear to have embraced this new ideology and used it to legitimize their authority, which is reflected in the city's architecture.

Main Structures

Cerros features several large pyramid temples, some of which are arranged around a central plaza. The largest of these is Structure 5C-2nd, which stands about 16 meters (52 feet) high. This pyramid is notable for its elaborate masks and other carvings, many of which represent aspects of Maya cosmology and the agricultural cycle.

Another significant structure at Cerros is the so-called "Temple of the Sacrificial Burial," which contains the tomb of a high-status individual. Many valuable artifacts were found in this tomb, including jade jewelry, ceramics, and shell inlays.

Decline and Abandonment

After about AD 150, the population of Cerros began to decline. By AD 400, the city had been largely abandoned. It's unclear why this happened, but it may have been due to a combination of political, economic, and environmental factors.

Today, Cerros is a popular tourist destination. Visitors can explore its ancient pyramids and plazas, learn about its history, and enjoy the beautiful surrounding landscape. The site also provides important insights into the early development of Maya civilization and the spread of new religious and political ideas during the Preclassic Period.

8. lamanai ruins

Lamanai is a significant archaeological site of the ancient Maya civilization located in Belize, Central America. The site lies along the banks of the New River Lagoon and was continuously occupied for over 3,000 years, from around 1500 BC to the 17th century AD, which is unusually long for a Mesoamerican site.

The name Lamanai comes from the Maya term "Lama'an/ayin," which translates to "submerged crocodile." Given that there are several crocodiles living in the surrounding tropical rainforest, this name is appropriate.

Here are some highlights of Lamanai:

High Temple (N10-43): Also known as the Temple of the Jaguar, this is the tallest structure at Lamanai, reaching a height of approximately 33 meters (108 feet). From the top, you can get a stunning view of the surrounding jungle and the New River Lagoon.

Mask Temple (N9-56): Named for the enormous 13-foot stone masks that adorn it, this temple is among the site's most famous structures. The masks are believed to represent ancient Maya rulers deified as gods.

The Mask temple

Jaguar Temple (N10–9): This temple is named for the boxy jaguar masks that decorate its base. These are the first known examples of Maya art to depict the jaguar, an animal that was considered sacred by the Maya and other Mesoamerican cultures.

Residential and Public Structures: Besides the temples, Lamanai also includes various residential structures, plazas, a ball court for playing the Maya ball game, and a few Christian artifacts, including the remnants of two Spanish churches and a sugar mill, evidencing Spanish colonial presence in the area.

The Stele: Lamanai is home to the second-longest known text in the country, inscribed on a giant slab of stone known as a stela. These inscriptions provide valuable information about the city's history.

Lamanai's remote jungle setting, combined with the impressive ruins and the opportunity to see a wide array of wildlife, make it a popular destination for tourists.

The Jaguar temple

Unlike some other Maya sites, much of Lamanai has yet to be uncovered, which makes it an important site for ongoing archaeological research. The site's long period of occupation provides an extended record of the evolution of Maya culture and society.

9. becan ruins

structure IX

Becán is an ancient Maya archaeological site located in the Mexican state of Campeche on the Yucatan Peninsula. The site was occupied from around 550 BC to AD 1200, but it reached its peak during the Late Classic period (AD 600–900). The name "Becán" is from the Yucatec Maya language and means "path of the serpent".

Site Layout and Architecture

Becán covers about 25 hectares and is surrounded by a moat, making it unique among Mayan sites. The moat is believed to have been both a defense mechanism and a symbol of Becán's political independence. Within the moat, the site is divided into several architecturally impressive complexes that include plazas, platforms, temples, and palaces.

The core of Becán consists of three main plazas, known as Plaza A, Plaza B, and Plaza C. Plaza B, the largest of the three, is surrounded by several impressive structures, including a large pyramid known as Structure IX (also referred to as Temple 9). This structure is about 32 meters (105 feet) tall and is one of the highest in the Rio Grande region.

Significant Features and Artifacts

structure VIII

One of the most significant structures at Becán is a tall pyramid temple known as Structure IX. This temple, which has been partially restored, is an excellent example of the Rio Bec architectural style, characterized by tall, narrow towers and elaborate façades.

Becán is also known for its stelae, carved stone monuments that were commonly erected in Maya cities. The stelae at Becán often depict the city's rulers and record significant events in their reigns.

Historical Importance and Modern Exploration

Becán was an important regional capital in the Rio Bec region during the Late Classic period. Its strategic location and defensive fortifications suggest that it was a significant political and military center.

Becán was first excavated by archaeologists in the 1930s, and significant research was conducted at the site in the 1970s. Despite these efforts, much of the site remains unexcavated, and there is still a lot to learn about its history and the people who lived there.

Today, Becán is a popular destination for tourists visiting the Yucatan Peninsula. Visitors can explore the site's impressive ruins, walk the ancient city's causeways, and climb to the top of Structure IX for a panoramic view of the surrounding jungle.

10. balakmu Ruins

main pyramid Str D5-5 south group

Balamku is an archaeological site of the Maya civilization located in the Mexican state of Campeche, on the Yucatan Peninsula. The name Balamku means "Jaguar Temple" in the Yucatec Maya language.

Balamku was occupied from around 300 BC to AD 1000, with its peak in the Late Classic Period (AD 600–900), like many other cities in the region.

Significant Structures

The site features several pyramid structures and plazas, the most famous being the "Temple of the Three Lintels.". However, Balamku's most significant feature is a well-preserved frieze discovered in 1990 in one of its buildings, named Structure I.

This frieze is one of the longest and best-preserved stucco friezes in the Maya world. It extends about 16.8 meters (55 feet) in length and stands about 1.9 meters (6.2 feet) tall. The frieze features a series of 20 complex figures depicting the Maya creation myth and the establishment of rulership, all of which are represented within the mouth of a giant monster, often interpreted as the entrance to the underworld.

Archaeological Importance

Balamku's well-preserved frieze provides important insights into Maya cosmology, mythology, and the ideology of kingship. It's considered a key piece of evidence for understanding the beliefs and rituals of the ancient Maya.

Despite the significance of the frieze, much of Balamku remains unexplored, and the site continues to be an area of interest for archaeologists studying the Maya civilization.

Today, Balamku is open to the public and offers visitors the chance to see its extraordinary frieze and other ruins firsthand. It's less visited than larger, more famous Maya sites like Chichen Itza or Tulum, offering a quieter, more secluded experience. Visitors should be aware that, due to its relative remoteness, facilities at Balamku are somewhat limited.

11. COPAN RUINS

Copán is one of the most significant archaeological sites of the ancient Maya civilization, located in western Honduras near the border with Guatemala. It was one of the most important cities of the Maya world, as well as one of the most beautiful, known for the intricacy of its art and the sophistication of its architecture and urban design.

Copán was occupied for more than two thousand years, from the Early Preclassic period (1500–900 BC) to the Postclassic period (AD 900–1500). The city reached its peak during the Classic period (AD 250–900), when it was the capital of a major Maya kingdom.

Hieroglyphic Stairway

One of the most impressive features of Copán is its hieroglyphic staircase, the longest text of ancient Maya hieroglyphic script ever discovered. The stairway is made up of thousands of individual glyphs, which together tell the dynastic history of the royal house of Copán.

Stelae

Temple 16

Copán is also known for its stelae—large stone slabs often covered with carvings and hieroglyphic text. The stelae at Copán are particularly noteworthy for their detailed and beautifully carved portraits of the city's rulers. Stela H, also known as the "Monument of the Moon," is one of the most famous of these, featuring a portrait of the 13th ruler of Copán, Waxaklajuun Ub'aah K'awiil.

Ball Court

The ball court at Copán is one of the largest and most impressive in the Maya world. The playing alley is flanked by sloping walls covered with intricate carvings, and the court is surrounded by a number of important buildings, including the Popol Nah (Council House).

Altar Q

This unique artifact is an important source of historical information about the site. The square-shaped altar is covered with the portraits of 16 rulers of Copán, depicted in chronological order.

Modern Exploration and Preservation

The ruins of Copán were rediscovered in the 19th century and have since been extensively studied and restored. The site is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the most popular tourist destinations in Honduras.

Despite extensive archaeological work, much of Copán remains unexcavated, and the site continues to be an important focus of ongoing research into the Maya civilization.

The History of Writing: Tracing the Development of expressing Language by Systems of Markings

Protowriting, ideographic systems, or early mnemonic symbols came before more advanced writing systems in the evolution of writing in human societies (symbols or letters that make remembering them easier).

A subsequent development is true writing, in which the content of a spoken language is encoded so that another reader may reasonably reconstruct the identical utterance written down. It differs from proto-writing, which frequently forgoes recording grammatical words and affixes, making it harder or even impossible to reassemble the precise meaning intended by the writer unless a substantial amount of context is already known in advance.

Writing innovations

The idea that writing originated in a single civilization and was called "monogenesis" persisted for a long time. According to academics, all writing originated in Mesopotamia's ancient Sumer and spread around the world as a result of cultural diffusion. This argument holds that traders or merchants traveling between geographical locations passed on the idea of representing language by written signs, though perhaps not necessarily the specifics of how such a system operated.

The finding of ancient Mesoamerican scripts, far from Middle Eastern sources, demonstrated, however, that writing had been created more than once. In at least four ancient civilizations, including Mesopotamia (between 3400 and 3100 BCE), Egypt (about 3250 BCE), China (1200 BCE), and lowland portions of southern Mexico and Guatemala, writing may have independently originated (by 500 BCE).

Some academics have suggested that ancient Egypt "The earliest authentic examples of Egyptian writing differ from Mesopotamian writing in both structure and style, indicating that they must have emerged independently. Although there is still a chance that Mesopotamian "stimulus dispersion" occurred, the influence could not have extended beyond the dissemination of an idea."

Because there is no evidence of communication between ancient China and the Near Eastern literate civilizations, as well as because Mesopotamian and Chinese approaches to phonetic representation differ, it is thought that ancient Chinese characters are independent creations.

The Vinča symbols.

The Rongorongo script of Easter Island, the Vina symbols from about 5500 BCE, and the Indus script of the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilization are all controversial. Since none have been translated, it is unclear if they all represent real writing, protowriting, or something entirely different.

The earliest coherent texts date from around 2600 BCE, and Sumerian archaic (pre-cuneiform) writing and Egyptian hieroglyphs are usually regarded as the earliest authentic writing systems. Both developed out of their ancestors' proto-literate symbol systems between 3400 and 3100 BCE. The Proto-Elamite script belongs to roughly the same time frame.

writing methods

Writing systems are distinct from symbolic communication systems. For most writing systems, reading a text requires some knowledge of the spoken language that goes along with it. In contrast, it's not always necessary to have a prior understanding of a spoken language to use symbolic systems like information signs, paintings, maps, and mathematics. Every human group has its own language, which is thought by many to be a natural and essential aspect of mankind.

Writing system development has been intermittent, uneven, and delayed, and old oral communication systems have only been partially replaced. Writing systems generally develop more slowly after they are formed than their spoken counterparts and frequently preserve traits and idioms that have been lost to the spoken language.

Three writing standards are thought to apply to all writing systems. First, writing must be comprehensive; it must have a meaning or purpose, and it must make a point or be able to convey that message. Second, whether they are physical or digital, all writing systems must include some kind of symbol that can be created on a surface. In order to facilitate communication, the writing system's symbols must resemble spoken words or speech.

The greatest advantage of writing is that it gives society a way to regularly and thoroughly preserve information—something that the spoken word could not previously do as successfully. Writing enables communities to communicate knowledge, transmit information, and

stages of development

Sumer

An ancient civilization of southern Mesopotamia, is believed to be the place where written language was first invented around 3200 BCE.

Beginning with the Neolithic pottery phase, when clay tokens were used to keep track of particular quantities of animals or other goods, writing first appeared. These tokens were initially imprinted on the exterior of spherical clay envelopes, which were later used to keep them. Afterwards, flat tablets were gradually introduced in place of the tokens, and signs were recorded using a stylus. Towards the end of the fourth millennium BCE, Uruk was where actual writing was first discovered. Other areas of the Near East quickly followed.

The earliest recorded account of the development of writing is found in a poem from ancient Mesopotamia:

The Lord of Kulaba patted some clay and wrote on it like a tablet because the messenger's mouth was heavy and he couldn't repeat the message. It has never been possible to write on clay before.

Enmerkar and the King of Aratta, a Sumerian epic written around 1800 BCE

Although there is agreement among scholars as to the difference between prehistory and the history of early writing, there is disagreement as to when proto-writing became "real writing." The criteria are somewhat arbitrary. In the broadest sense, writing is a way of keeping track of information. It is made up of graphemes, which in turn can be made up of glyphs.

Many centuries of shattered inscriptions typically follow the advent of writing in a particular region. The presence of coherent texts in a culture's writing system is how historians determine a culture's "historicity".

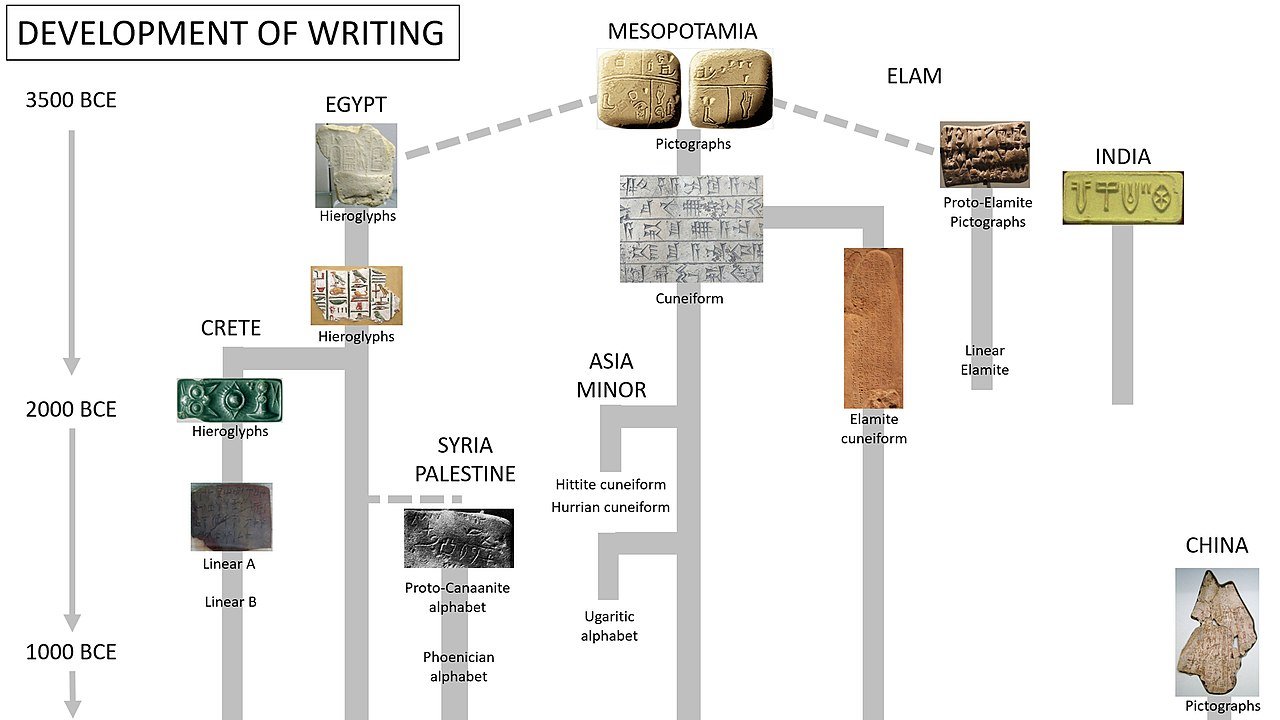

Standard reconstruction of the development of writing. There is a possibility that the Egyptian script was invented independently from the Mesopotamian script.

A conventional "proto-writing to true writing" system follows a general series of developmental stages:

Picture writing system: glyphs (simplified pictures) directly represent objects and concepts. In connection with this, the following substages may be distinguished:

Mnemonic: glyphs primarily as a reminder.

Pictographic: glyphs directly represent an object or a concept such as (A) chronological, (B) notices, (C) communications, (D) totems, titles, and names, (E) religious, (F) customs, (G) historical, and (H) biographical.

Ideographic: graphemes are abstract symbols that directly represent an idea or concept.

Pre-cuneiform tags, with drawing of goat or sheep and number (probably "10"): "Ten goats", Al-Hasakah, 3300–3100 BCE, Uruk culture.

Transitional system: graphemes refer not only to the object or idea that it represents but to its name as well.

Phonetic system: graphemes refer to sounds or spoken symbols, and the form of the grapheme is not related to its meanings. This resolves itself into the following substages:

Verbal: grapheme (logogram) represents a whole word.

Syllabic: grapheme represents a syllable.

Alphabetic: grapheme represents an elementary sound.

Designs on some of the labels or token from Abydos, carbon-dated to circa 3400–3200 BC and among the earliest form of writing in Egypt. They are remarkably similar to contemporary clay tags from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

The best known picture writing system of ideographic or early mnemonic symbols are:

Jiahu symbols, carved on tortoise shells in Jiahu, c. 6600 BCE

Vinča symbols (Tărtăria tablets), c. 5300 BCE[24]

Early Indus script, c. 3100 BCE

In the Old World, true writing systems developed from neolithic writing in the Early Bronze Age (4th millennium BC).

Locations and timeframes

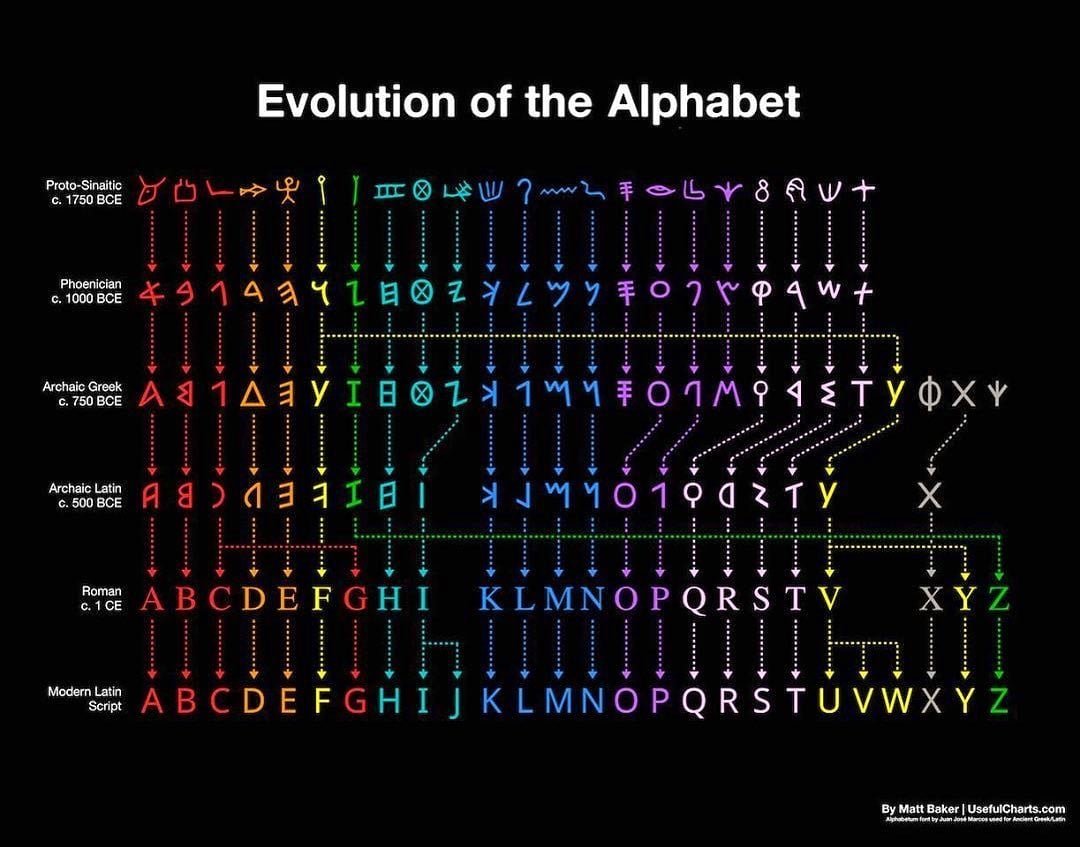

Comparative evolution

from pictograms to abstract shapes, in Mesopotamian cuneiforms, Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese characters

Proto-writing

The first writing systems of the Early Bronze Age were not a sudden invention. Rather, they were a development based on earlier traditions of symbol systems that cannot be classified as proper writing, but have many of the characteristics of writing. These systems may be described as "proto-writing". They used ideographic or early mnemonic symbols to convey information, but it probably directly contained no natural language. These systems emerged in the early Neolithic period, as early as the 7th millennium BC, and include:

The Jiahu symbols found carved in tortoise shells in 24 Neolithic graves excavated at Jiahu, Henan province, northern China, with radiocarbon dates from the 7th millennium BCE. Most archaeologists consider these not directly linked to the earliest true writing.

Vinča symbols, sometimes called the "Danube script", are a set of symbols found on Neolithic era (6th to 5th millennia BCE) artifacts from the Vinča culture of Central Europe and Southeast Europe.

The Dispilio Tablet of the late 6th millennium may also be an example of proto-writing.

The Indus script, which from 3500 BCE to 1900 BCE was used for extremely short inscriptions.

The Dispilio Tablet

The Dispilio tablet is a wooden tablet bearing inscribed markings, unearthed during George Hourmouziadis's excavations of Dispilio in Greece, and carbon 14-dated to 5202 (± 123) BC.

It was discovered in 1993 in a Neolithic lakeshore settlement that occupied an artificial island near the modern village of Dispilio on Lake Kastoria in Kastoria, Western Macedonia, Greece.

Even after the Neolithic, a number of societies used proto-writing as a transitional form before adopting formal writing. Such a mechanism might have existed in the quipu of the Incas (15th century CE), often known as "talking knots". Another example is the pictographs created by Uyaquk before the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language developed the Yugtun syllabary around 1900.

Ancient writing

The Bronze Age saw the development of writing in a wide range of cultures. Indus script, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Cretan hieroglyphs, Chinese logographs, Sumerian cuneiform writing, and the Olmec script of Mesoamerica are a few examples. Around 1600 BCE, the Chinese script most likely evolved apart from the Middle Eastern scripts. It is also generally accepted that the pre-Columbian Mesoamerican writing systems, which include the Olmec and Maya scripts, had separate origins. In 2000 BCE, it is believed that the first real alphabetic writing was created for Hebrew laborers in the Sinai by assigning Semitic values to mostly Egyptian hieratic characters (see History of the alphabet and Proto-Sinaitic alphabet).

Ethiopia's Geez writing system is regarded as Semitic. With roots in the Meroitic Sudanese ideogram system, it is most likely of semi-independent origin. The majority of alphabets used today are either direct descendants of this one invention, many through the Phoenician alphabet, or were designed in direct response to it. The early Old Italic alphabet and Plautus (c. 750–250 BCE) were separated by around 500 years in Italy, while the Elder Futhark inscriptions and early works like the Abrogans (c. 200–750 CE) are separated by a similar amount of time in the case of the Germanic peoples.

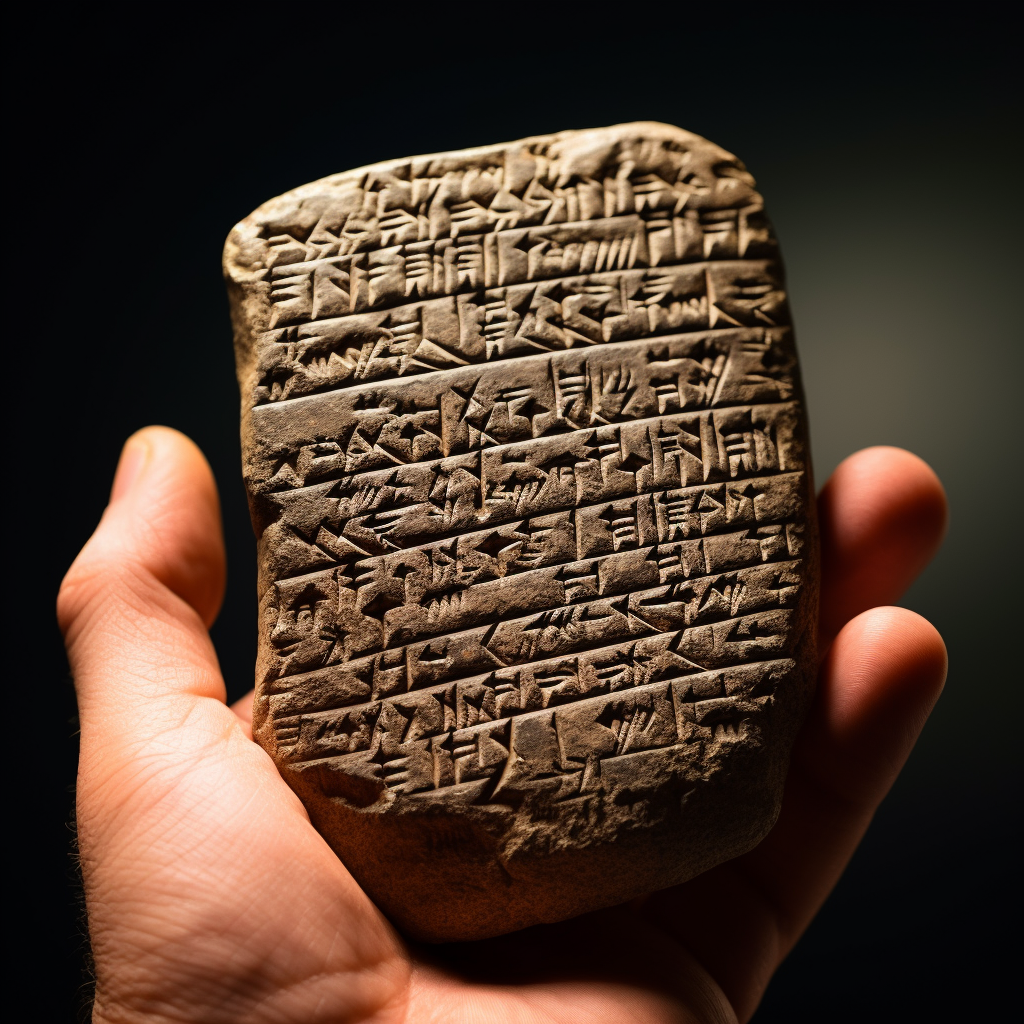

Cuneiform writing

The first Sumerian script was derived from a system of clay tokens used to denote different types of goods. This had developed into a system of keeping accounts by the end of the fourth millennium BC, utilizing a stylus with a circular form that was impressed into soft clay at various angles to record numbers. A pointed stylus was used to gradually add pictographic lettering on this to show what was being counted. Writing using a wedge-shaped stylus (hence the name "cuneiform") began to include phonetic features by the 29th century BCE and gradually replaced writing with a round stylus and a sharp stylus by about 2700–2500 BCE.

Cuneiform first started to represent Sumerian syllables around 2600 BCE. Ultimately, cuneiform writing evolved into a general-purpose system for writing numerals, syllables, and logograms. This alphabet was adapted to the Akkadian language starting in the 26th century BCE, and from there to others like Hurrian and Hittite. This writing system resembles Old Persian and Ugaritic scripts in appearance.

Hieroglyphics from Egypt

Literacy was concentrated among a well-educated elite of scribes, who played a crucial role in upholding the Egyptian empire through writing. To become scribes in the employ of temple, royal (pharaonic), and military authority, one had to come from a certain background.

According to Geoffrey Sampson, the general concept of expressing words from a language in writing was likely transmitted to Egypt via Sumerian Mesopotamia. Egyptian hieroglyphs "came into being a little after Sumerian script, and, possibly [were], invented under the influence of the latter." Despite the significance of early Egypt-Mesopotamia links, "no definitive judgment has been established as to the genesis of hieroglyphics in ancient Egypt" due to the lack of direct evidence. However, it is stated and agreed upon that "a very compelling argument can also be made for the independent development of writing in Egypt" and that "the evidence for such direct influence remains fragile."

Egyptian writing does suddenly appear at that time, but Mesopotamia has an evolutionary history of sign usage in tokens dating back to around 8000 BCE. Since the 1990s, discoveries of glyphs at Abydos, dated to between 3400 and 3200 BCE, may challenge the conventional idea that the Mesopotamian symbol system predates the Egyptian one. These glyphs were discovered in tomb U-J at Abydos; they were written on ivory and most likely served as labels for other items discovered there.

Even though he acknowledged that Egypt's geographic location made it a receptacle for many influences, Egyptian scholar Gamal Mokhtar maintained that the inventory of hieroglyphic symbols originated from "fauna and flora used in the signs [which] are essentially African" and that in regards to writing, "we have seen that a purely Nilotic, therefore African origin not only is not excluded, but probably reflects the reality."

Elamite writing

The unintelligible Proto-Elamite writing first appears around 3100 BCE. Around the latter third millennium, it is thought to have evolved into Linear Elamite, which was later supplanted by Elamite Cuneiform, which was adapted from Akkadian.

Indus script

Most inscriptions containing these symbols are extremely short, making it difficult to judge whether or not these symbols constituted a writing system used to record the as yet unidentified language(s) of the Indus Valley civilisation.

The Indus script has been assigned to markings and symbols discovered at numerous Indus Valley civilization sites due to the hypothesis that they were used to transcribe the Harappan language. It is disputed whether the script, which was in use from roughly 3500 to 1900 BCE, is a Bronze Age writing script (logographic-syllabic) or merely proto-writing symbols. According to analysis, it was written in boustrophedon or from right to left.

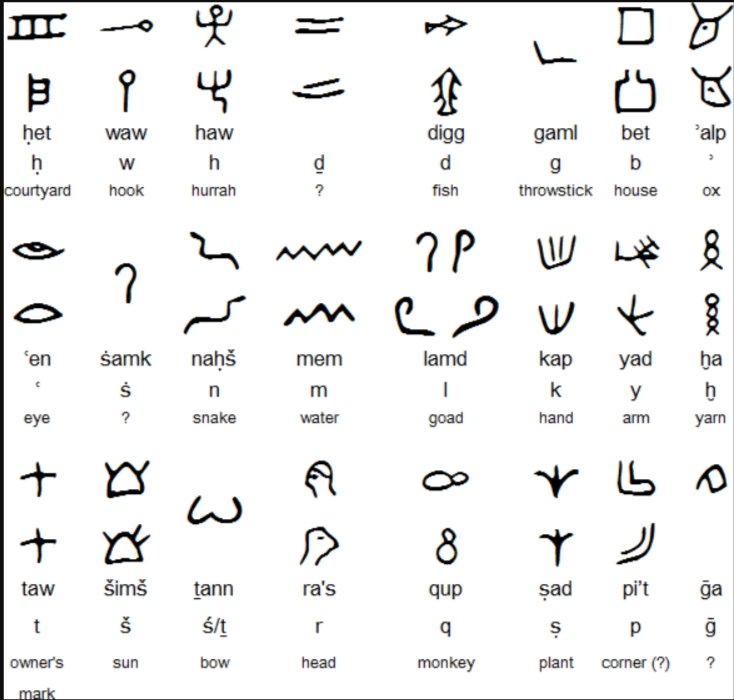

early SEMITIC ALPHABETS

Around 1800 BCE in Ancient Egypt, the first "abjads," which mapped individual symbols to individual phonemes but not necessarily each phoneme to a symbol, appeared as a representation of the language created there by Semitic workers. However, by that time, alphabetic principles had only a remote chance of being ingrained into Egyptian hieroglyphs for upwards of a millennium.

Did the Proto-Canaanite alphabet take its symbols independently of the hieroglyphs?

It is only until the end of the Bronze Age that the Proto-Sinaitic script separates into the Proto-Canaanite alphabet (c. 1400 BCE), Byblos syllabary, and the South Arabian alphabet (c. 1200 BCE). These early abjads remained of minor significance for several decades. The untranslated Byblos syllabary most likely had some influence on the Proto-Canaanite, which in turn provided inspiration for the Ugaritic alphabet (c. 1300 BCE).

Anatolian hieroglyphs

The Luwian language was written down using Anatolian hieroglyphs, a native hieroglyphic script found in western Anatolia. Around the fourteenth century BCE, it initially appeared on royal seals of the Luwians.

Chinese characters

The corpus of inscriptions on oracle bones and brass from the late Shang dynasty is the earliest authenticated example of the Chinese script that has been found so far. The oldest of these is believed to date from about 1200 BCE.

There have been recent finds of tortoise-shell carvings from around 6000 BCE, such as Jiahu Script and Banpo Script, but it is debatable whether or not the carvings are complex enough to be considered writing. 3,172 cliff carvings from the period between 6000 and 5000 BCE have been found near Damaidi in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. They contain 8,453 different characters, including images of the sun, moon, stars, gods, and scenes of grazing or hunting.

Replica

of ancient Chinese script on an oracle turtle shell

These pictographs are thought to resemble the first Chinese characters that have been confirmed to be written. Writing in China would predate Mesopotamian cuneiform, traditionally recognized as the first manifestation of writing, by about 2,000 years if it were to be considered a written language. However, it is more likely that the inscriptions represent a type of proto-writing, comparable to the modern European Vinca script.

Early Greek and Cretan scripts

Cretan relics include hieroglyphic writing (early-to-mid-2nd millennium BCE, MM I to MM III, overlapping with Linear A from MM IIA at the earliest). The Mycenaean Greek writing system, Linear B, has been decoded, but Linear A has not yet been. The three overlapping, but distinct, Aegean pre-alphabetic writing systems can be categorized according to their chronological order and geographic distribution as follows:

Cretan Hieroglyphic / Crete (eastward from the Knossos-Phaistos axis) / c. 2100−1700 BCE

Linear A / Crete (except extreme southwest), Aegean Islands (Kea, Kythera, Melos, Thera), Greek mainland (Laconia) and west Minor Asia (Miletus and maybe Troy) / c. 1800−1450 BCE

Linear B / Crete (Knossos), and mainland (Pylos, Mycenae, Thebes, Tiryns) / c. 1450−1200 BCE

The archaeological finds with signs of pre-alphabetic scripts in the Aegean

(Up) The finds with signs of Linear B script reach about 6,000 and constitute the majority of the pre-alphabetic written monuments of the Aegean.

(Middle) About 1,400 are the finds which imprint Linear A and make up a 11% of all pre-alphabetic inscriptions.

(Down) Cretan hieroglyphics occupies 2% of the available finds with only 400 finds.

Illustration: Dimosthenis Vasiloudis

Mesoamerica

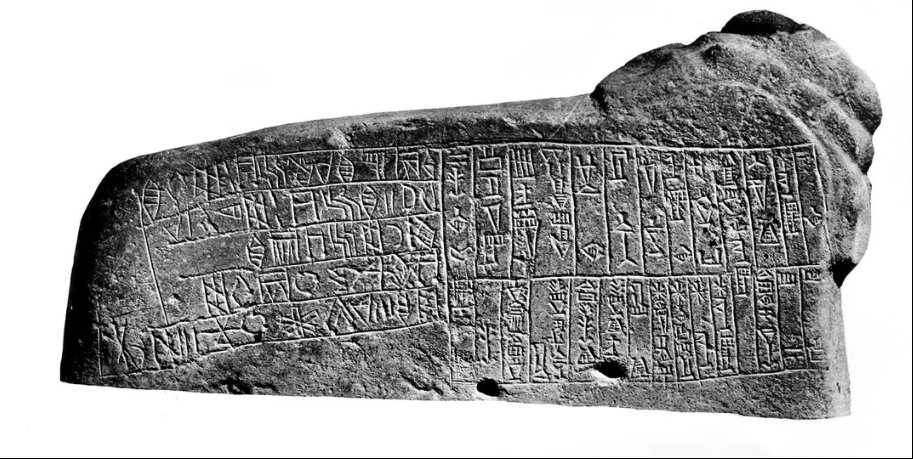

The Cascajal Block, a stone slab with 3,000-year-old writing that predates the first Zapotec writing from around 500 BCE, was found in the Mexican state of Veracruz. It is an example of the oldest script in the Western Hemisphere.

Stela 12 and 13

from the southern end of Building L, in the Zapotec city of Monte Albán, Outside of Oaxaca, Mexico.

The Maya script is one of numerous pre-Columbian scripts found in Mesoamerica, and it appears to have been the most well-developed and extensively deciphered. The earliest clearly identifiable Maya inscriptions date to the third century BCE, and writing continued to be used until just before the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the sixteenth century BCE. A combination of logograms and syllabic symbols, utilized in Maya writing, is somewhat reminiscent of current Japanese writing.

IRON AGE WRITING

The Proto-Canaanite alphabet, which was used into the Iron Age, is all that the Phoenician alphabet is (conventionally taken from a cut-off date of 1050 BCE). The Greek and Aramaic alphabets were derived from this alphabet. They eventually gave rise to the writing systems that are currently used everywhere, from Western Asia to Africa and Europe. The Greek alphabet, on the other hand, was the first to use specific symbols to represent vowel sounds.

By Matt Baker

In the first centuries of the Common Era, the Greek and Latin alphabets gave rise to a number of European scripts, including the Runes, Gothic, and Cyrillic alphabets, while the Aramaic alphabet developed into the Hebrew, Arabic, and Syriac abjads, the latter of which spread as far as Mongolian script. The Ge'ez abugida originated from the South Arabian alphabet. According to some academics, the Indian Brahmic family also descended from the Aramaic alphabet.

GRAKLIANI HILL WRITING

At Georgia's Grakliani Hill, behind a fallen altar from a temple dedicated to a fertility goddess from the seventh century BCE, an obscure script was uncovered in 2015. Grakliani's other temples' inscriptions, which depict animals, people, or decorative features, are different from these ones. Although its letters are rumored to be connected to ancient Greek and Aramaic, the script has no similarities to any known alphabet. In contrast, the earliest Armenian and Georgian letters come from the fifth century CE, right after the respective nations converted to Christianity. The inscription looks to be the oldest local alphabet ever uncovered in the entire Caucasus region. An portion of the inscription measuring 31 by 3 inches had been unearthed by September 2015.

Grakliani script on the basement of altar of goddess of fertility (XI-X c. BC)

Vakhtang Licheli, director of the State University's Institute of Archaeology, claims that "The writings on the temple's two altars have been kept in remarkably good condition. While the pedestal of the second altar is entirely covered with writings, the first altar has few clay letters carved into it." Unpaid students made the discovery. Inscriptions from Grakliani Hill were sent to Miami Laboratory in 2016 for beta analytic radiocarbon dating, which revealed that they were created between c. 1005 and c. 950 BCE.

WRITING IN THE GRECO-ROMAN WORLD

When the Greeks adopted the Phoenician script for use with their own language in the early eighth century BCE, the history of the Greek alphabet officially began. The Greek and Phoenician alphabets share a lot of similarities in terms of their characters, and both alphabets nowadays are written in the same order. The Phoenician system's adapter(s) added three letters to the conclusion of the series, known as the "supplementals." The Greek alphabet evolved into a number of different forms.

Early Greek alphabet on pottery in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

One was utilized in southern Italy and west of Athens and is known as Western Greek or Chalcidian. The other variant, known as Eastern Greek, was spoken by the Athenians and in modern-day Turkey before spreading over the rest of the Greek-speaking world. The Greeks initially elected to write like the Phoenicians, from right to left, but subsequently switched to left to right. The lines would then alternately read from left to right, then from right to left, and so on. On occasion, though, the writer would begin the next line where the preceding one ended. Up until the sixth century, this style of writing, called "boustrophedon," mirrored the course of an ox-drawn plough.

Italic scripts and Latin

Cippus Perusinus

Etruscan writing near Perugia, Italy, the precursor of the Latin alphabet

All of the contemporary European scripts have their roots in Greek. The Latin alphabet, named after the Latins, a central Italian people who came to rule Europe with the emergence of Rome, is the most widely used descendant of the Greek script. Around the fifth century BCE, the Etruscan civilization, which employed a multitude of Italic scripts descended from the western Greeks, taught the Romans how to write. The other Old Italic scripts have not survived in very large quantities due to the cultural hegemony of the Roman state, and the Etruscan language is largely extinct.

WRITING DURING THE MIDDLE AGES

Roman rule in Western Europe fell apart, and the Persian Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire became the main centers of literary development. Latin, which was never a major literary language, lost prominence quickly (except within the Roman Catholic Church). Greek and Persian were the two main literary languages, but Syriac and Coptic were also significant.

Arabic quickly became a significant literary language in the area as a result of the development of Islam in the 7th century. Greek's status as a scholarly language soon lost ground to Arabic and Persian. The Turkish and Persian languages now use Arabic script as their principal writing system. The development of the cursive scripts for Greek, the Slavic languages, Latin, and other languages was also greatly inspired by this script.

The Hindu-Arabic numeral system was also extended throughout Europe thanks to the Arabic language. The modern Spanish city of Cordoba had emerged as one of the world's leading intellectual hubs by the start of the second millennium and was home to the largest library at the time. Its location at the meeting point of the Islamic and Western Christian worlds encouraged intellectual growth and written exchange between the two cultures.

THE MODERN ERA AND THE RENAISSANCE

By the 14th century, Western Europe had experienced a renaissance, which had temporarily increased the significance of Greek while slowly restoring Latin's status as an important literary language. In Eastern Europe, particularly in Russia, a comparable but smaller emergence took place. As the Islamic Golden Era came to an end, Arabic and Persian also started to slowly lose ground. In order to codify the phonologies of the various languages, the Latin alphabet underwent several alterations as a result of the rebirth of literary development in Western Europe.

Writing has undergone steady change throughout history, in large part because of the emergence of new technologies. Technology advancements such as the printing press, computer, mobile phone, and pen have all changed how and what is written as well as the medium in which it is generated. Characters can now be generated with a button press rather than a hand motion, especially with the development of digital technology like the computer and the smartphone.

The rope bridges of the Incas: The ancient technology that united Andean communities fades into history

A remarkable ancient technology and tradition that united communities in the Andes is fading into history.

Reconstruction of the Tinkuqchaka bridge is here almost complete.

Cirilo Vivanco

By LIDIO VALDEZ AND CIRILO VIVANCO

ONE EARLY JANUARY morning in the mid-1980s after a daylong journey from Ayacucho (formerly “Guamanga”), I (Lidio) found myself being guided across a small rope bridge hanging across the Pampas River. This was my first experience on such a bridge, made with an astonishing ancient technology that uses twisted branches to form a crossing. Although it looked to be only about 20 meters long, the bridge, called Chuschichaka, was beautiful: a reminder of ancient times, when similar bridges existed along trails and roads that linked the Inca Empire.

From the town of Chuschi, where I started my journey that day, my destination of Sarhua seemed to be just nearby. But because of the rugged landscape, the trip was long and exhausting: It took hours to hike the distance, with the rope bridge in the middle. At last, our team arrived in Sarhua and was welcomed by the community with food, drinks, music, and dance. Their hospitality made our visit an incredible and unforgettable experience.

My mission at that time as an archaeologist was to investigate ancient agricultural terraces in the region. As I prepared for my work, I was told that there was an important activity taking place that day: the reconstruction of a larger bridge nearby called Tinkuqchaka.

Except for a few older and younger people who were staying in the town, most community members were already on their way to the site of Tinkuy (a name that means “a place to meet,” “a place to play,” or “a place to fight”) to take part in bridge reconstruction. Sadly, I could not spare the time to attend, though I would hear all about such work later from my friend and colleague—anthropologist Cirilo Vivanco (co-author), who is originally from Sarhua.

When I left the community three days later in the early hours of the morning, Tinkuqchaka was not yet finished. We crossed the partially constructed bridge by flashlight, holding the handrails tightly.

THE ANCIENT PRACTICE of making hanging bridges has existed for a long time in Peru—perhaps going back as far as the Wari culture, which thrived from A.D. 600–1000. At one time, dozens of such bridges are thought to have connected communities across gorges and rivers. Today only a few remain, mainly for the sake of tourists, and even they are falling into disrepair. Just this April, the most famous of them—Queshuachaca, near the former Inca capital of Cuzco—collapsed from lack of maintenance.

The global appreciation of the hanging bridges of the Andes goes a long way back. In 1877, American archaeologist E. George Squier published Peru: Incidents of Travel and Exploration in the Land of the Incas, in which he devoted a few pages to the great hanging bridge over the Apurímac River on the main road to Cuzco. The bridge was built over a gigantic valley, enclosed by enormous and steep mountains. The over 40-meters-long structure, entirely made of plant materials, was hung from massive cliffs on both sides. To Squier, the bridge looked like a mere thread, a frail and swaying structure, yet frequently crossed by people and animals, the latter carrying loads on their backs. Travelers timed their day’s journey to reach the bridge in the early hours of the day before the strong winds came that made the bridge sway “like a gigantic hammock.”

This drawing from American archaeologist E. George Squier’s 1877 book on Peru shows a rope bridge over the Apurímac River.

E. George Squier/Wikimedia Commons

Squier was very impressed, saying that his crossing was an experience he “shall never forget.” His description and accompanying image of the bridge no doubt captured the imagination of everyone who got ahold of Peru: Incidents of Travel and Exploration in the Land of the Incas—including American explorer Hiram Bingham, famous for reporting the existence of the spectacular Inca city of Machu Picchu to a global audience in 1911. According to historians, one of the reasons Bingham decided to go to Peru in the first place was precisely the illustration of the Apurímac hanging bridge he saw in Squier’s book.

Long before Squier, Spaniards were impressed with the Inca hanging bridges too. Early Spaniards, such as Pedro de Cieza de León, were fascinated. But the arrival of the Spaniards had devastating effects for local Indigenous peoples. Europeans brought diseases that decimated the Indigenous populations. Communities were reduced or totally deserted. Spaniards’ interest in precious minerals, such as gold and silver, also switched the efforts of Indigenous peoples to other activities, often leaving unattended other communal obligations, such as building the bridges.

Tinkuqchaka was one of the few bridges to survive into the 2000s.

THREE YEARS AFTER my first trip to Sarhua, I was back again, this time on a mission to register the archaeological sites scattered around Sarhua along with Cirilo, as we recently published in the Journal of Anthropological Research. On our way, we crossed Tinkuqchaka again and bathed in the Pampas River below the bridge.

As we watched the bridge swaying delicately over the river, Cirilo told me about how Tinkuqchaka, being built entirely of plant material, required annual maintenance and a total renewal every two years. He told me, too, how the community, including himself, came together to do this. From my conversations with Cirilo, the story of this touching activity became clear to me.

Catherine Gilman/SAPIENS

Following ancient Andean ideals, the community of Sarhua is divided into two groups or ayllus. One of the ayllus is regarded as local while the other is said to be made up of “outsiders,” perhaps the descendants of peoples who were relocated by the Inca from elsewhere within the Inca realm. Both ayllus coexist side by side, and it is believed that such a division is necessary to maintain a balance needed for the well-being of the community. Sarhua residents do not usually highlight their group membership, except during communal activities like the bridge rebuilding.

One person, named by the community, is responsible for looking after the bridge. As in Incan times, the title of this person is chakakamayuq. Bridge renewal begins with a notification by the chakakamayuq to the community, which begins collecting the necessary construction material—the branches of a bush named pichus. Then, on a specified day, community members descend from Sarhua, carrying on their shoulders pichus branches to Tinkuy.

Kumumpampa, an open space found near the bridge, is the gathering place. At this location, both ayllus take their respective positions, the local ayllu closer to Sarhua and the ayllu of outsiders closer to the Pampas River, symbolically distant from Sarhua. After necessary logistical discussions, the ayllus exchange jokes and challenge each other, thus making the whole activity an entertainment or spectacle. For the participants, it is a competition between the two ayllus but also a game, time to play and time to tease and mock the opposition.

The task ahead for both ayllus is, first, to produce 23 ropes 100 meters long, called aqaras, from the pichus branches. Bundles of nine pichus branches are tied together and braided. The ayllu that produces more ropes will be declared the winner. Defeat is shameful, and thus both ayllus strategize to ensure victory. This is largely a male activity, but women of both ayllus are engaged by preparing meals and cheering for their respective side, mocking the men of the opposite ayllu.

Community members work hard to secure the heavy cables.

Cirilo Vivanco

Producing the aqaras is only the first challenge. The second task is to produce five thicker cables from the aqaras. This is a more difficult job. Starting at a middle point, teams from the ayllus build half of the cable working outward, again in competition. Experienced members are in charge, while younger members observe, fully aware that in the future it will be their turn. At the end, one of the ayllus emerges the winner and is celebrated with loud shouts. Victory is sweet and joyful, while defeat is ugly, painful, and agonizing.

Upon completing the five cables, work shifts to the edge of the river, on either side of which stands a stone tower. Members of the outsider ayllu cross to the opposite side of the river using the old bridge for one last time; then the old bridge is cut at both ends and is carried downstream by the Pampas River, thus marking the end of a cycle and reinforcing, temporarily, the separation of the outsiders.

The whole task of completing the bridge takes about five days.

The renewal of Tinkuqchaka illustrates the complementary role of the ayllus and their necessary reunion for the vitality of the community. Local ayllu members throw ropes to the opposite bank of the river, retaining one end in their hands. Since bridge construction takes place during the rainy season, when the river carries lots of water, this is not an easy task. The local ayllu ties the rope to the first thick cable so it can be pulled across the river. The cables are as thick as a person’s body, made of wet branches and heavy. It takes hours to pull the five cables across the river and tie each securely behind the stone tower on the far side.

Three cables, pulled taut and horizontal, become the base of the bridge over which small sticks are laid transversely and fastened to the cables by cords. Two smaller cables become the handrails.

The whole task of completing the bridge takes about five days, during which time the entire community remains at Tinkuy. While the days are spent working, evenings are time to socialize, drink, sing, and dance, and thus renew the sense of community. The community, aware of the historical significance of the bridge, is also proud of being responsible for carrying forward this tradition.

THE TECHNOLOGY EMPLOYED to build Tinkuqchaka appears to be ancient. The manner by which the bridge is built perhaps also resembles ancient customs. No one knows for sure. The fact that communities such as Sarhua are capable of undertaking such impressive construction and engineering feats shows the power of unified action.

There is the possibility that hanging bridges predate the Inca Empire. Large sections of the Inca royal highway already existed before the Incas, and along the same roads, there were several river crossings, thus suggesting that the bridge technology already existed. Demonstrating this possibility, of course, is not easy. There are no written records from this time, and the plant material of the bridges left no archaeological traces.

The hanging bridge constitutes an important symbol of the technology developed by the forebears of the Indigenous peoples of this region (including myself and Cirilo). In a perfect world, it would be rightfully considered a monument to the creativity and imagination of the Indigenous peoples of the Andes and maintained to showcase to the world this unique achievement of unknown origins.

The local and outsider ayllus gather on opposite sides of the river.

Cirilo Vivanco

Of course, there is no such perfect world, and decision-makers have other priorities. As Andean philosophy teaches, everything has an end. The hanging bridges are not an exception.

For the residents of Sarhua, a cable bridge was built in 1992 that effectively ended the biennial construction of the rope bridges. In 2007, a larger bridge that could carry cars was built. Tinkuqchaka was made anew in 2010 and reconstructed for the last time in 2014 for the sake of tourism. The local youth seem uninterested in renewing the tradition.

It appears we have come to witness the end of something wonderful, unique, and to foreign eyes, spectacular. Something that was present almost everywhere in this region is fading away forever, and some of us who had the fortune to see and walk on these bridges sometimes took them for granted, without realizing that within our lifetime an important chapter of Andean history was coming to an end.

Archaeologists plan to fully restore ancient Mayan temples

Archaeologists from the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History began restoration work on an ancient Mayan temple in the Dzibilchaltun archaeological site in eastern Mexico.

Watch the video below:

Archeologists uncover ancient civilization burial sites in Peru

Archeologists found seven burial sites belonging to an ancient civilization dating from VII and XII A.D in Huarmey, Peru.

The discovery made by Polish archeologists in western Peru is related to the Wari culture and reveals the existence of an elite group of artisans dedicated to manufacturing pieces of great ornamental value.

The burials belong to two women, two men, two children and a young man, among which was the bundle of a personage dressed with jewelry, ceramics, textiles, tools and handicrafts.

The new finding is related to a previous one made in 2012, near the current tomb, where a mausoleum of 64 Wari women was found.

1,000 years ago, a woman was buried in a canoe on her way to the 'destination of souls'

The woman was on her 'final voyage."

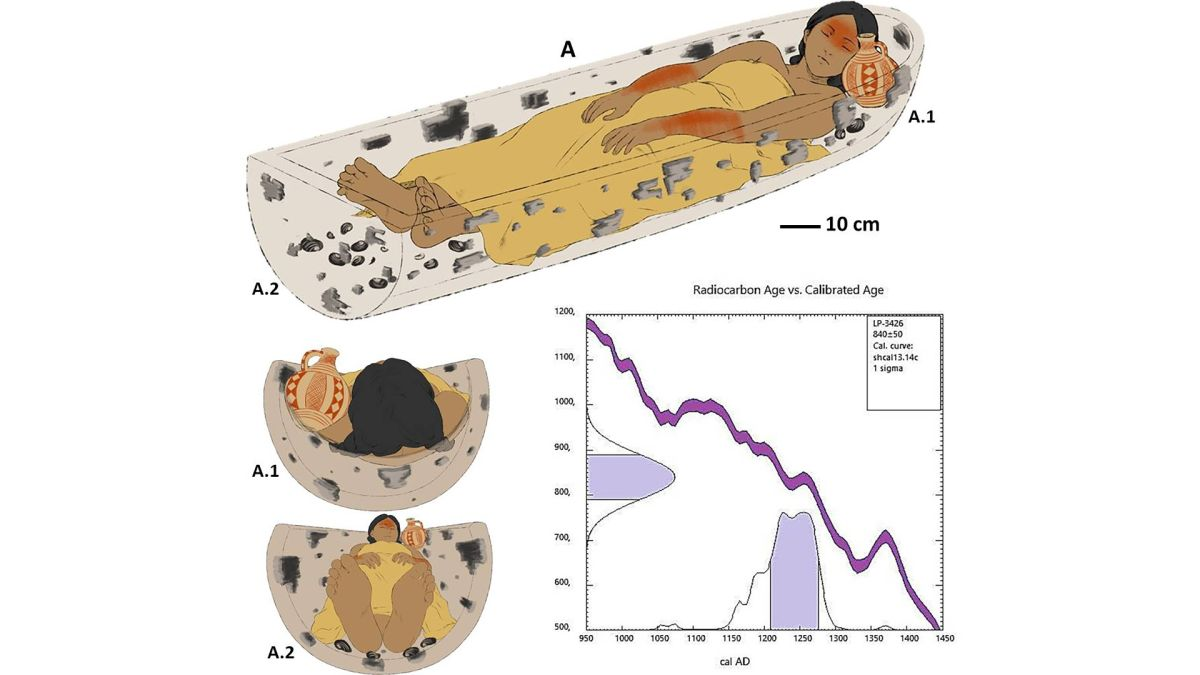

An illustration of deceased young woman lying in a wampos (ceremonial canoe) with a pottery jug near her head. (Image credit: Pérez et al., 2022, PLOS ONE, CC-BY 4.0)

Up to 1,000 years ago, mourners buried a young woman in a ceremonial canoe to represent her final journey into the land of the dead in what is now Patagonia, a new study finds.

The discovery reaffirms ethnographic and historical accounts that canoe burials were practiced throughout pre-Hispanic South America and refutes the idea that they may have been used only after the Spanish colonization, according to the authors of the study.

"We hope this investigation and its results will resolve this controversy," said archaeologist Alberto Pérez, an associate professor of anthropology at the Temuco Catholic University in Chile and the lead author of the study, published Wednesday (Aug. 24) in the journal PLOS One(opens in new tab).

Canoe burials are well attested and are still practiced in some areas of South America, Pérez told Live Science. But because wood rots rapidly, the new finding is the first known evidence of the practice from the pre-Hispanic period. "The previous evidence was important and was based on ethnographic data, but the evidence was indirect," he said.

The archaeological site in the northwest of Argentina was excavated between 2012 and 2015 before a well was built at the location, which is on private land. (Image credit: Pérez et al., 2022, PLOS ONE, CC-BY 4.0)

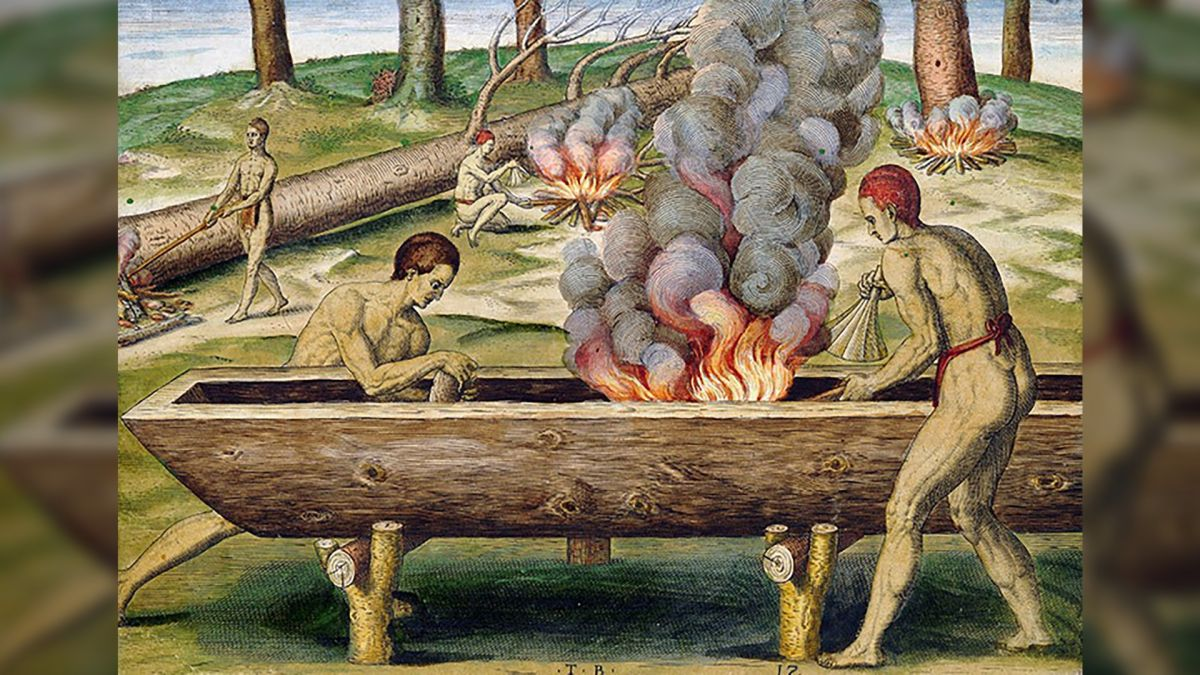

The burial described in the study, at the Newen Antug archaeological site near Lake Lacár in western Argentina, indicates that mourners buried the woman on her back in a wooden structure crafted from a single tree trunk that had been hollowed out by fire.

The same burning technique has been used for thousands of years to make "dugout" canoes known as "wampos" in the local Mapuche culture, and evidence suggests that Indigenous people prepared the woman's remains so that she could embark on a final canoe journey across mystical waters to her final abode in the "destination of souls," Pérez said.

Pre-Hispanic burial

The woman's grave is the earliest of three known pre-Hispanic burials at the Newen Antug site, which archaeologists excavated between 2012 and 2015, before a well was built at the location, which is on private land. The location is at the northern extreme of the region known as Patagonia, which consists of the temperate steppes, alpine regions, coasts and deserts of the southern part of South America.

Radiocarbon dating indicates the woman was buried more than 850 years ago and possibly up to 1,000 years ago, while her sex and age at death — between 17 and 25 years old — were estimated from her pelvic bones and the wear on her teeth, according to the study. (Evidence suggests the Mapuche have lived in the region since at least 600 B.C.)

A pottery jug decorated with white glaze and red geometric patterns, placed in the grave by her head, suggests a connection with the "red on white bichrome" tradition of pre-Hispanic ceramics on both sides of the Andes mountains, the researchers found. This is the earliest known example of this type of pottery being used as a grave gift, according to the study.

Canoes known as wampos in the Mapuche language were constructed by hollowing out a single tree trunk with fire, with thicker walls at the bow and stern. (Image credit: Pérez et al., 2022, PLOS ONE, CC-BY 4.0)

Given its age and the humid climate, the burial canoe has rotted away, and only fragments of wood remain. But tests suggest that the fragments came from the same tree — a Chilean cedar (Austrocedrus chilensis) — and that it had been hollowed out with fire.