Deep inside a limestone cave on Muna Island, off the coast of Sulawesi in Indonesia, archaeologists have uncovered a remarkable ancient secret.

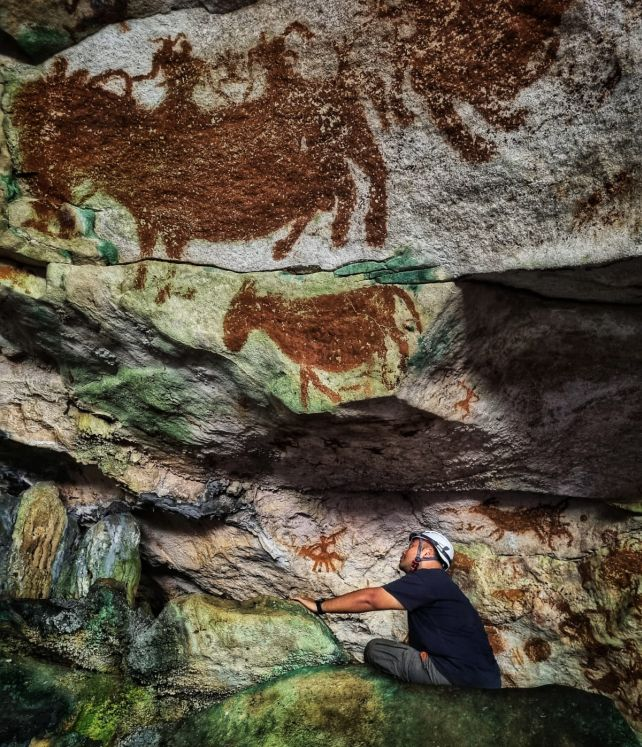

A research team has identified human-made rock art that is older than any other reliably dated example known so far, with a minimum age of 67,800 years. The haunting hand stencils, marked by elongated, pointed fingers, offer crucial insight into early human migration and cultural expression in the region tens of thousands of years ago.

“What we are seeing in Indonesia is probably not a collection of isolated discoveries,” said archaeologist Maxime Aubert of Griffith University in Australia, who co-led the study, speaking to ScienceAlert. “Rather, it is the gradual unveiling of a much deeper and older cultural tradition that was simply invisible to us until recently.”

According to Aubert, the sheer quantity and great antiquity of rock art in Indonesia show that the region was far from peripheral. Instead, it appears to have been a cultural heartland where early humans lived, moved through landscapes, and expressed ideas through art for many millennia.

In recent years, Sulawesi and the Indonesian part of Borneo have emerged as unexpectedly significant regions for understanding early human creativity and migration. Many cave paintings in these areas were discovered decades ago, but for a long time researchers lacked reliable methods to determine their age.

With advances in dating techniques, scientists have now established that some of these artworks are far older than previously believed, with minimum ages exceeding 40,000 years and, in some cases, more than 51,000 years.

“Each time we apply these methods in new regions, the dates turn out to be much older than expected,” Aubert explained. “This tells us that the issue was not that early humans suddenly began making art in one location, but that we were looking in the wrong places, or not looking closely enough.”

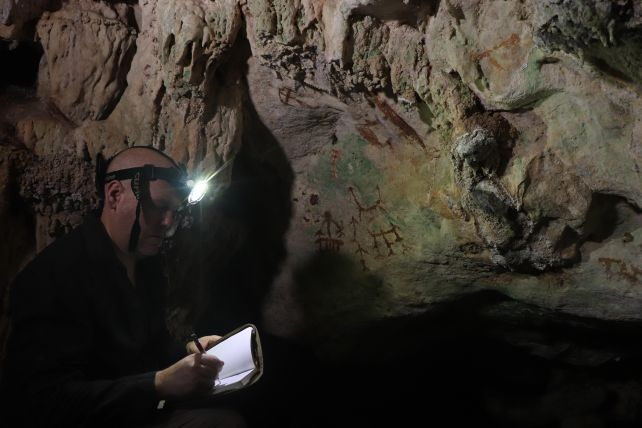

The latest discovery comes from Liang Metanduno, a cave long known to contain ancient rock art. Aubert and his colleagues set out to determine how the artworks in this cave fit into the broader timeline of prehistoric art across the Indonesian archipelago.

Maxime Aubert in Liang Metanduno.

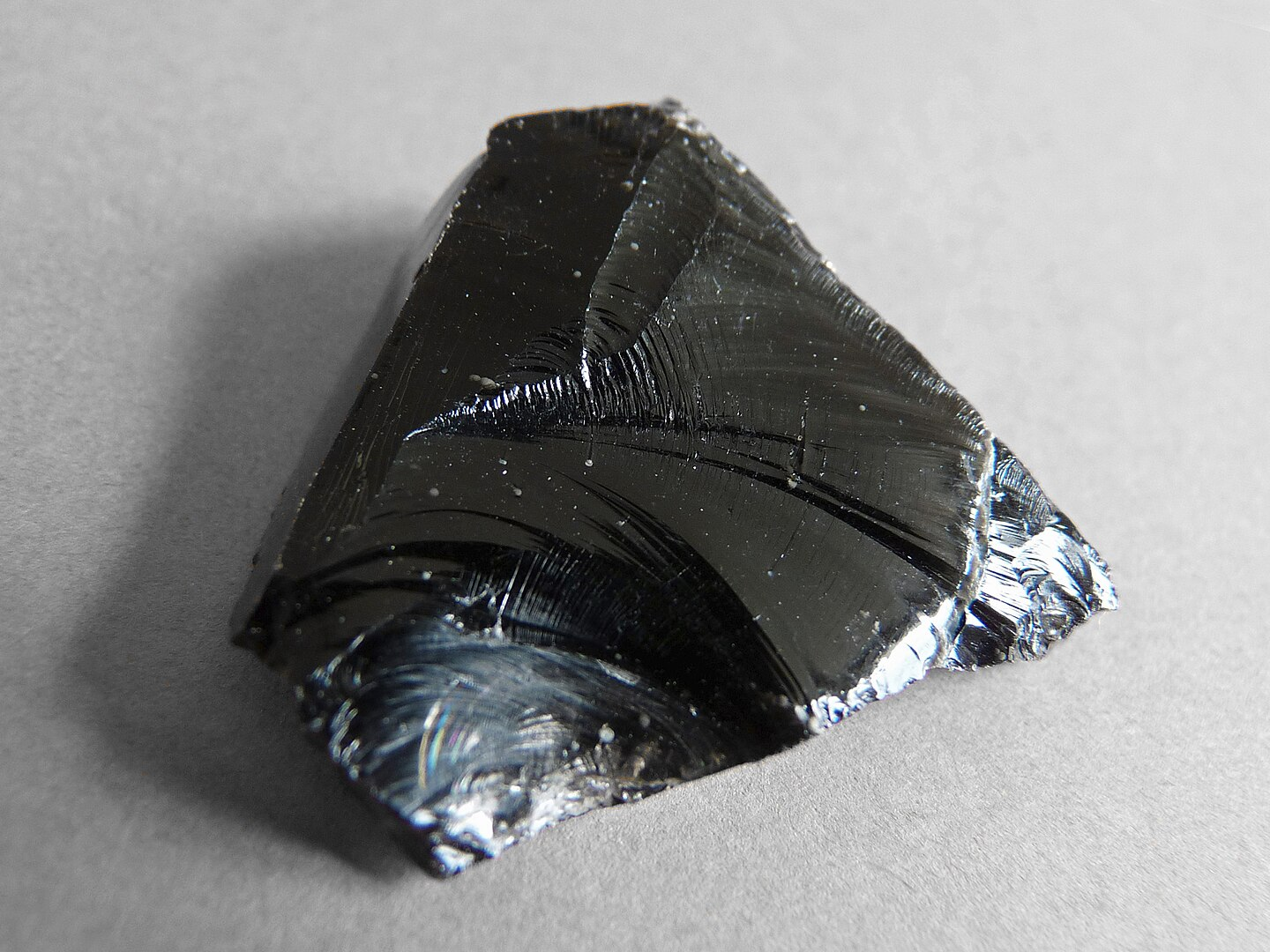

If conditions are right, a thin layer of calcite can slowly form over rock art over thousands of years, deposited by water flowing across the stone surface. This water often contains small amounts of uranium, which dissolves easily. Over time, the uranium naturally decays into thorium, an element that does not dissolve in water.

Because the rate of this radioactive decay is precisely known, scientists can measure the ratio of uranium to thorium in the calcite layer to calculate when it formed.

This means the artwork itself was not directly dated to 67,800 years ago. Instead, that age applies to the mineral crust that developed on top of the painting. The art beneath must therefore be at least that old.

Taken together with earlier findings, this evidence suggests that much of the rock art in the region may be far older than previously thought—significantly reshaping our understanding of Sulawesi’s deep human past.

Archaeologist Shinatria Adhityatama of Griffith University and the Indonesian National Archaeology Research Institute working in the cave.

Aubert suggested that art may have taken on greater importance as human populations increased and interactions between groups became more frequent.

He explained this through a modern analogy: traffic lights are essential in large cities but unnecessary in small villages. In much the same way, art, symbols, and shared imagery may have helped early people communicate identity, belonging, and shared meaning as social networks grew larger and more complex.

For archaeologists, the significance of this symbolic behavior lies in when and where it appears. The newly dated artworks are located along a proposed northern migration route believed to have been used by early modern humans as they moved through Island Southeast Asia toward Sahul—the Ice Age landmass that once connected Australia and New Guinea. Evidence of sophisticated artistic traditions along this route helps bridge a long-standing gap between early sites in mainland Asia and the earliest traces of humans in Australia, supporting the idea that people may have reached Sahul as early as 65,000 years ago.

The discovery also raises compelling new questions: how much more rock art from this period remains undiscovered, how symbolic traditions spread across regions, and whether even earlier chapters of this cultural story are still hidden.

“What excites us most is that this art shows early people in Southeast Asia were already expressing ideas, identity, and meaning through images tens of thousands of years ago,” Aubert said. “These were not isolated experiments, but part of a long-standing cultural tradition.”

He added that the finding is not a conclusion, but an invitation—to continue searching and uncovering more of humanity’s deep past.