More than 4,000 years of history in only 16 square miles

An aerial view of Kuwait’s Failaka Island shows four different sites representing thousands of years of civilization. (Courtesy Flemming Højlund, Kuwaiti-Danish Mission)

A forgotten sliver of land in the far north of the Persian Gulf, Kuwait’s Failaka Island is home now mostly to camels. Its only town is a sprawling ruin pockmarked with bullet holes and debris from tank rounds, and the landscape beyond seems empty and bleak. Even before Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait prompted its sudden evacuation, Failaka in the past century was little more than a quiet refuge for fishermen and the occasional Kuwaiti seeking relief from the mainland’s fierce heat. But just under the island’s sandy soil, archaeologists are discovering a complex history extending back 4,000 years, from the golden age of the first civilizations to the wars of the modern era.

The secret to Failaka’s rich past is its location, just 60 miles south of the spot where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers empty into the Gulf. From the rise of Ur, the world’s largest metropolis in the late third millennium B.C., until Saddam Hussein’s attack during the First Gulf War, the island has been a strategic prize. For thousands of years, Failaka was a key base from which to cultivate and protect—or prey on—the lucrative trade that passed up and down the Persian Gulf. In addition, there were two protected harbors, potable water, and even some fertile soil. The island’s relative isolation provided a safe place for Christian mystics and farmers amid the rise of Islam in the seventh and eighth centuries A.D., as well as for pirates a millennium later.

Currently, archaeological teams from no less than half a dozen countries, including Poland, France, Denmark, and Italy, are at work on Failaka. Given the political volatility of neighboring nations such as Iraq, Iran, and Syria, the island offers a welcome haven for researchers unable to conduct their work in many other parts of the region. “I started encouraging teams to come in 2004,” says Shehab Shehab, Kuwait’s antiquities director. “And I want to encourage more.”

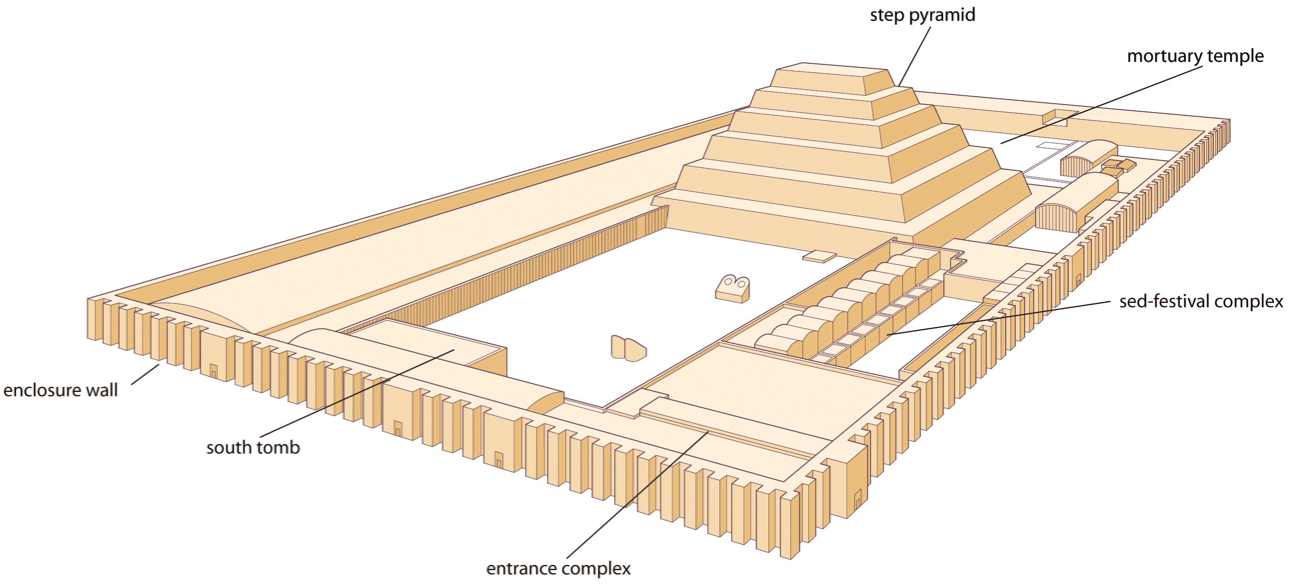

The oldest settlement on Failaka was long thought to have been founded in about 1800 B.C. by the Dilmunites, a maritime people who likely hailed from what are today’s Bahraini and Saudi Arabian coasts, and who controlled Persian Gulf trade. But on Failaka’s southwest corner, a team from Denmark’s Moesgård Museum has uncovered evidence that Mesopotamians arrived at least a century before the Dilmunites. The finds are centered on a recently unearthed Mesopotamian-style building typical of those found on the nearby Iraqi mainland dating from around 2000 B.C. The structure was later partially covered by a Dilmunite temple.

In the mythology of ancient Sumeria (modern Iraq), Dilmun is described as an Eden-like place of milk and honey. But by 2000 B.C., Dilmunites were leaving their homeland to become seagoing merchants and establish a powerful trading network that eventually stretched from India to Syria. Mesopotamian clay tablets refer to ships from Dilmun bringing wood, copper, and other goods from distant lands. By the nineteenth century B.C., Failaka had become a linchpin in the Dilmunites’ operations. At this point, after the Dilmunites had either ousted the Mesopotamians or merely succeeded them, there are no further signs of a Mesopotamian presence. The Dilmunites constructed a large temple and palace complex almost on top of the houses built by the earlier Mesopotamian residents. A French team that excavated the temple in the 1980s suggested that it was an oddity, possibly related to Syrian temple towers. But recent work by a team from the Moesgård Museum in Denmark points to a building remarkably similar to the Barbar sanctuary in Bahrain, considered the grandest Dilmun structure.

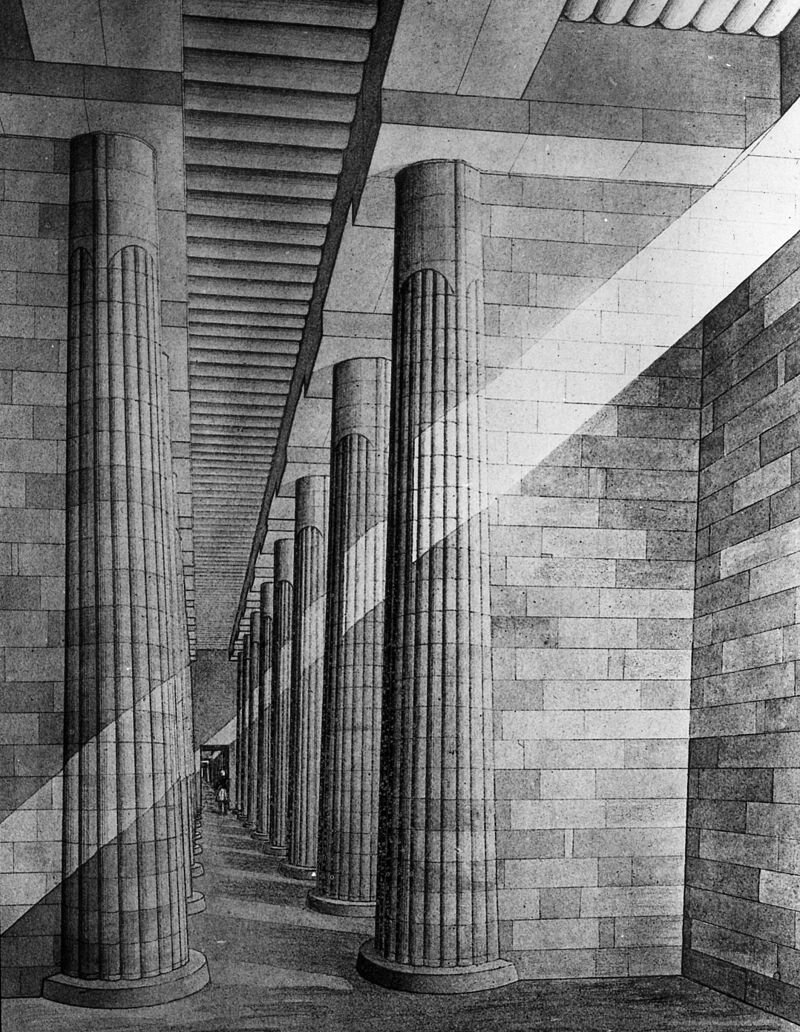

Failaka’s name is derived from the Greek word for outpost. But Alexander the Great, according to later classical authors such as Strabo and Arrian, gave Failaka the name Ikaros, since it resembled the Aegean island of that name in size and shape. French archaeologists working on the island in recent years have found several stone inscriptions dating to the fourth and third centuries b.c. mentioning the name Ikaros, as well as architecture and artifacts that reveal a bustling community with international ties during that period. The island’s accessible fresh water, easily defended coastline, and strategic location also attracted the attention of Alexander’s successors, who vied among themselves for control of regional trade routes. Antiochus I, who ruled the Seleucid Empire in the third century B.C., built a 60-foot-square fort around a well on Failaka. Inside the fortress compound, one small, elegant temple has Ionic columns and a plan that is quintessentially Greek, including an east-facing altar. This was no simple import, however, but a fascinating amalgamation of designs. The column bases, for example, are of the Persian Achaemenid style, similar to those in the capital, Persepolis, burned by Alexander’s troops in the fourth century B.C.

The center of Failaka is a low-lying swampy area that is now the province of mosquitoes and wandering white camels that belong to the Kuwaiti emir. But a millennium ago, this was a three-square-mile pocket of fertile and well-watered plain cultivated by a small community of isolated Christians in a region populated by Muslims. Previous French excavations revealed several villages and two churches, including a possible monastic chapel. A Polish team led by Warsaw-based archaeologist Magdalena Zurek is now busy excavating nearby sites to understand the extent of the settlements that flourished in the eighth and ninth centuries A.D., several hundred years after the faith inspired by Muhammad swept through the region. “We know nothing about Christians on Failaka,” says Zurek, who suspects that a third church lies near her current excavation of a modest farmstead.

The story of Failaka after the abandonment of the Christian villages remains shadowy. Currently archaeologists are turning their attention to several sites that sit along the northern shore of the island to probe the medieval and early modern periods. The most interesting is located on a high spot overlooking the gulf, facing Iraq. Nearly 30 years ago, a team from the University of Venice surveyed the site, pinpointing a village, called Al-Quraniya, that dates to at least as early as the seventeenth century A.D., and possibly several centuries earlier. In 2010, an Italian team led by Gian Luca Grassigli of the University of Perugia began intensive fieldwork there. The excavators have since uncovered an array of pottery, porcelain, glass bangles, and bronze objects, including nails and coins, dating to between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries A.D. The mound seems to have two large concentrations of building materials, and the archaeologists hope to make a detailed plan of the settlement in future campaigns. Deeper trenches may reveal evidence of earlier settlement, filling in the long gap between the abandonment of Christian villages and more recent times.

What is clear is that Failaka was still a notable outpost two millennia after Alexander. Just to the southeast of the village is a small square rock fort dating to about the sixteenth or seventeenth century. Some researchers believe that this structure was constructed by Portuguese soldier-merchants who did frequent business in the region. others suspect that Arab pirates built the base to attack the lucrative shipping lanes that led to wealthy Iraqi cities such as Basra or to ports along the Iranian coast to the east. In this era, european, Iranian, and chinese elites had a growing appetite for the gulf pearls that dominated the region’s economy. Pirates were a constant threat until the nineteenth century; British guns and diplomacy put an end to their raids.

Pirate hideout. (Courtesy Kuwaiti-Italian Mission)

The mainland of Kuwait is mostly harsh desert, with only a handful of significant ancient sites. Even the old town of Kuwait City, dating back two centuries, was long ago demolished to make way for skyscrapers. Thus Failaka is of prime importance to the country’s heritage. Recently, much of the island’s history was threatened by a plan to transform the barren land with its rocky coast into a major tourist magnet, complete with marinas, canals, spas, chalets, and enormous high-rise hotels and condominiums. In the wake of the global economic recession, however, the $5 billion project foundered, and was recently shelved. Shehab has moved into the resulting vacuum, lobbying hard to turn all of Failaka into a protected site in order to enable archaeologists to uncover, study, and preserve this small nation’s past.

The government already sets aside more than $10 million annually to cover the costs of foreign projects in Kuwait, and hopes to promote science as well as encourage heritage tourism. “Shehab’s dream is to create in Kuwait a kind of research center for Gulf basin archaeology,” says archaeologist Piotr Bielinski from the University of Warsaw, who is digging at a prehistoric site on the mainland just north of Kuwait City. And excavators on Failaka are making the most of this unique opportunity, exposing evidence of Mesopotamian merchants, religious structures representing three cultures and spanning more than 2,500 years, a pirate’s lair, and the remains of Failaka’s last battle, ample testimony to the island’s millennia-long endurance.

By ANDREW LAWLER

![screenshot-www.culture.gov.gr-2021.09.07-21_15_56https_www.culture.gov.gr_el_Information_SitePages_view.aspx_nID=3934&fbclid=IwAR36aTey5gRC9VXO4ojhQhznquFn9eI-QPFpWcs3m_OpqrTNs_V5-4a9W-0_prettyPhoto[Gallery]_3_{date}.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6047d405b02148755fb6e601/1631038628230-5R32F4XYYBNL6VL7M90M/screenshot-www.culture.gov.gr-2021.09.07-21_15_56https_www.culture.gov.gr_el_Information_SitePages_view.aspx_nID%3D3934%26fbclid%3DIwAR36aTey5gRC9VXO4ojhQhznquFn9eI-QPFpWcs3m_OpqrTNs_V5-4a9W-0_prettyPhoto%5BGallery%5D_3_%7Bdate%7D.jpg)

![A general view from the restoration of the theatre in the ancient city of Laodikea, Denizli, western Turkey [Credit: Anadolou Agency]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6047d405b02148755fb6e601/1629895858947-71NC8ITZAMIOUDUUO95P/Laodikeia-02.jpg)