Archaeologists have formally confirmed that architectural remains discovered in the centre of Fano are those of the long-lost basilica designed by Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, the Roman architect whose treatise De Architectura became the cornerstone of Western architectural theory. The announcement, made today at the Mediateca Montanari, has been hailed by Italian officials as a landmark discovery that reshapes both Fano’s historical identity and scholarly understanding of Roman architectural practice.

The remains lie beneath Piazza Andrea Costa, at the heart of the city, and represent the first physical evidence of a building directly attributed to Vitruvius. Although many ancient structures have long been associated with him on stylistic or theoretical grounds, this is the first time archaeology has confirmed a building that Vitruvius himself claimed to have designed and constructed.

A centuries-long search

The Basilica of Vitruvius has been sought for generations. In Book V of De Architectura, Vitruvius described the building as a rectangular basilica enclosed by a peristyle of columns. Despite repeated excavations and numerous hypotheses over the centuries, no conclusive remains had previously been identified.

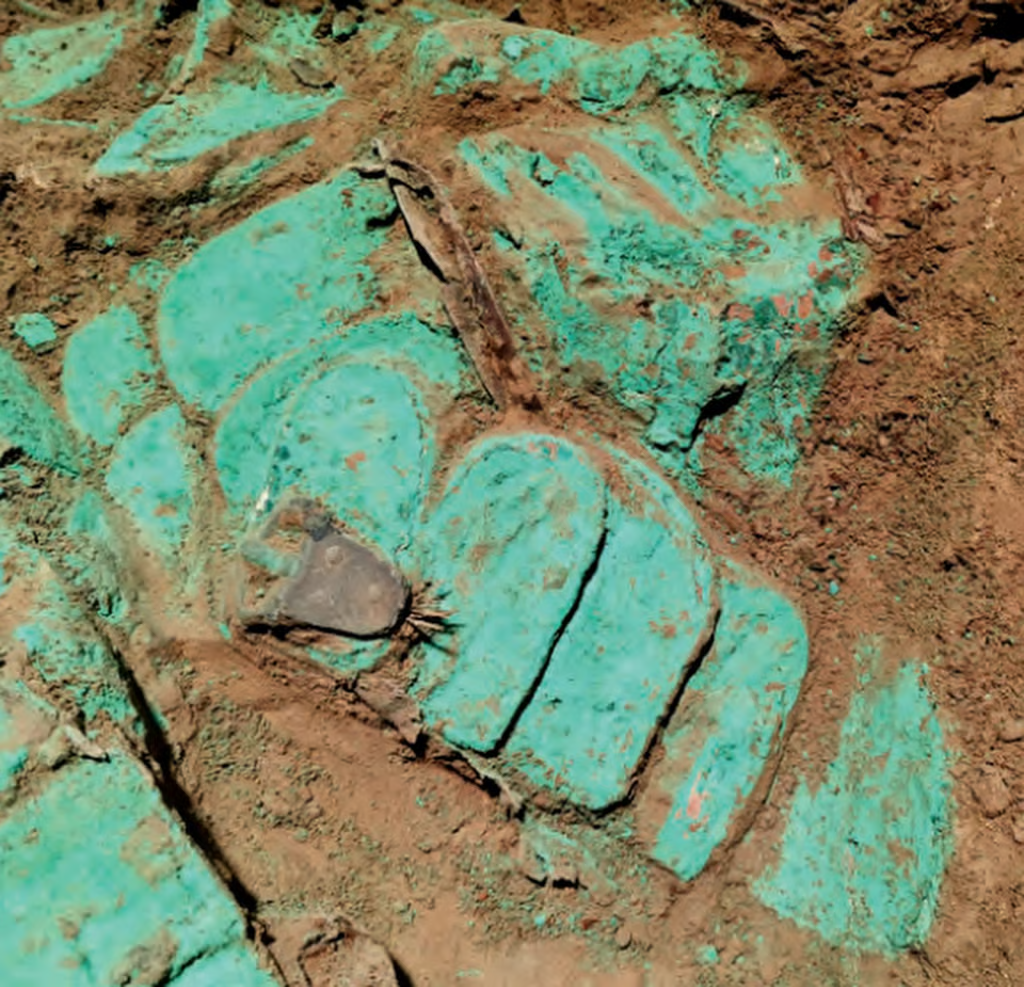

Momentum shifted in 2023, when renovation works on a property in Via Vitruvio unexpectedly exposed substantial Roman walls and marble flooring. These finds pointed to a prestigious public building, possibly administrative or ceremonial, but further investigation was constrained by modern construction above the site.

The current excavation, undertaken as part of the redevelopment of Piazza Andrea Costa, has now provided decisive evidence. A detailed stratigraphic investigation uncovered foundations and column bases belonging to a monumental basilica that closely matches Vitruvius’ own description.

Evidence that confirms the attribution

The building’s layout mirrors Vitruvius’ account with striking accuracy: a rectangular plan bordered by a colonnade, with eight columns along the long sides and four on the shorter sides. The discovery of a fifth corner column proved crucial, allowing archaeologists to establish the building’s precise orientation and full footprint.

The scale of the columns is particularly remarkable. On-site measurements indicate diameters of approximately five Roman feet—around 147 to 150 centimetres—and an estimated original height of about 15 metres. The columns were integrated with pilasters and corner supports, forming a sophisticated structural system capable of carrying an upper level. This approach reflects Vitruvius’ characteristic balance between structural efficiency and harmonious proportions.

Specialists have highlighted the extraordinary correspondence between the excavated remains and the dimensions inferred from De Architectura. In what has become a defining statement of the discovery, researchers note that the plan reconstructed from Vitruvius’ text aligns with the archaeological evidence “to the centimetre.”