An inscription dating back to the Qin Dynasty, discovered on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau, connects the legendary Kunlun Mountains to a real geographic location, prompting a reassessment of China’s early western frontier.

A recently authenticated stone carving found on the windswept plateau is transforming our understanding of early Chinese civilization. Known as the Garitang Engraved Stone, the inscription shows that the influence of the Qin Dynasty reached much farther into the western highlands than scholars had previously assumed. It records an imperial journey ordered by Emperor Qin Shihuang in 210 BC, during which envoys traveled toward the fabled Kunlun Mountains in search of medicinal plants associated with the quest for immortality. Written in small seal script and located near the northern shore of Gyaring Lake, the inscription offers rare physical evidence of cultural exchange, geographic exploration, and long-distance communication at the very beginning of China’s imperial age.

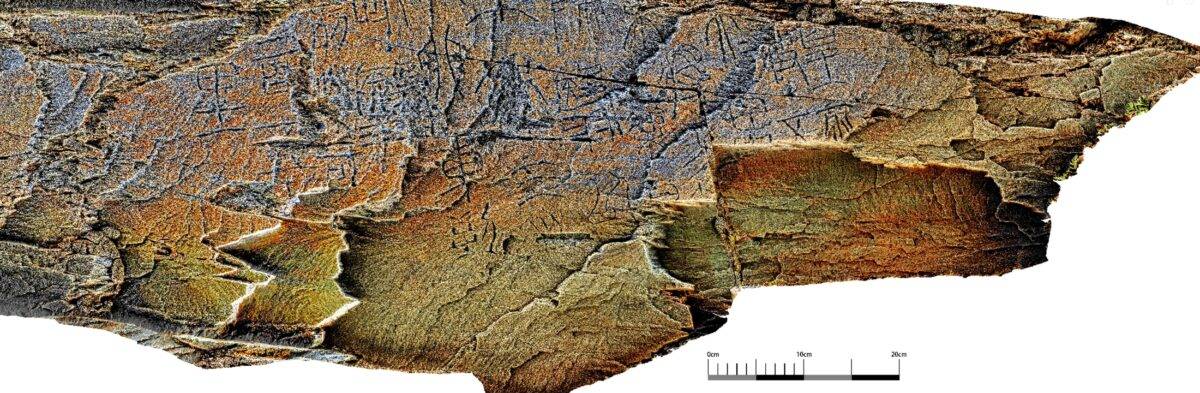

Standing before the stone today, one can almost picture the moment of its creation: exhausted court envoys guiding a carriage across the desolate plateau after a long, bitter journey from the Qin capital of Xianyang, stopping beneath a rocky outcrop to carve a brief record of their progress before continuing toward the sacred peaks. For more than two millennia, this message lay exposed to wind, snow, and isolation, until modern researchers rediscovered it and confirmed that it was neither myth nor hearsay, but the authentic trace of a state-sponsored expedition — the highest-altitude Qin-era inscription ever identified.

The importance of the stone lies not only in its dramatic location, but in the historical insight it provides. The text records that the envoys’ carriage reached the site on the jimao day of the third month in the thirty-seventh year of Qin Shihuang’s reign, noting that Kunlun lay 150 li farther ahead. This precise geographic detail anchors a once-mythical landscape to a real place, situating Kunlun near the source region of the Yellow River and bridging ancient cosmology with a tangible, navigable world. What had long belonged to legend and poetry is here preserved in stone as evidence of actual movement across the plateau.

To confirm the inscription’s authenticity, archaeologists and cultural heritage experts conducted extensive multidisciplinary investigations at the site. They employed high-resolution photogrammetry, 3D modeling, and microscopic analyses of weathering patterns to study every incision, crack, and tool mark in the quartz sandstone. The carving techniques matched those of the Qin period, mineral deposits within the characters indicated prolonged natural exposure, and the surrounding terrain showed that the stone had remained in its original position since antiquity. Far from a later reproduction, the Garitang inscription stands as a genuine and undisturbed record from the final years of the Qin Empire.

The Garitang Keshi, or the Garitang Engraved Stone.

Beyond confirming its authenticity, the stone also overturns long-held ideas about how early China expanded and engaged with its frontier regions. The journey described in the inscription could not have taken place without assistance from local plateau communities who understood the terrain, climate, and travel routes. Rather than depicting a one-directional imperial push into an uninhabited wilderness, the discovery points to shared navigational knowledge, guidance, and a form of cultural interaction shaped jointly by the Central Plains and highland societies. The mission to collect medicinal herbs from Kunlun thus reflects not only imperial ambition, but also communication, cooperation, and contact across diverse landscapes.

The inscription further reveals the early roots of transportation networks that would later develop into major trans-Asian corridors. The mention of a carriage reaching the lakeside site implies the presence of defined routes and established pathways leading toward the source region of the Yellow River — the early foundations of what would eventually become the Qinghai branch of the Silk Road and the Tang–Xizang Ancient Road. Long before these routes were formally recorded, the Garitang stone shows that movement, exchange, and mobility were already shaping the Qin Dynasty’s western frontier.

At the same time, the discovery reinvigorates the Kunlun myth itself. For thousands of years, Kunlun has stood as a powerful symbol in Chinese cosmology — a sacred mountain linked to creation, immortality, and the connection between Heaven and Earth. The inscription captures the moment when this symbolic landscape entered the realm of physical geography. It shows that by the late Qin period, Kunlun was not only imagined, but actively pursued, approached, and incorporated into imperial missions and state knowledge. Myth and geography no longer exist separately; instead, they meet on the plateau, reflecting a fusion of belief and exploration.

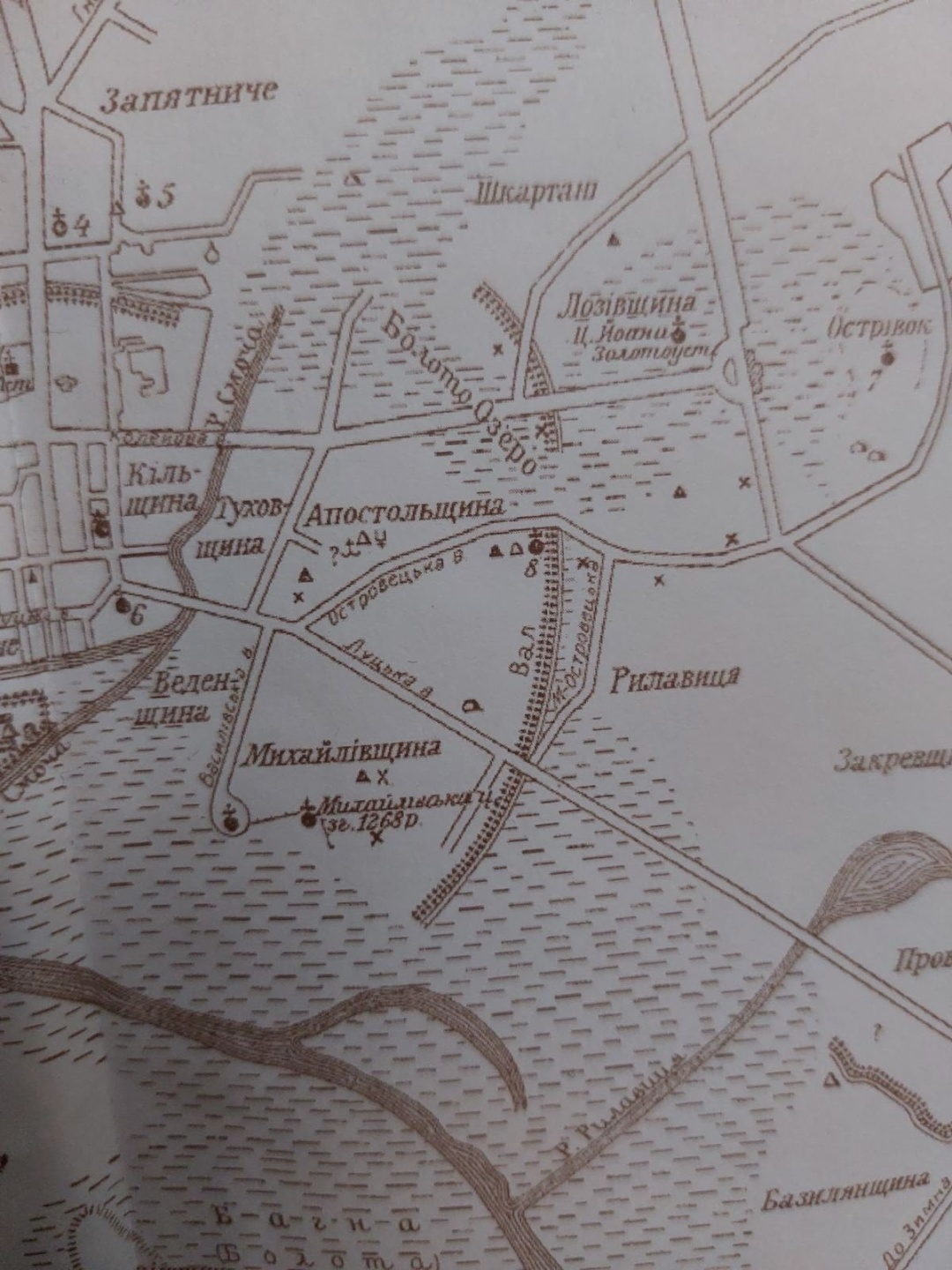

The location of the Garitang Keshi engraved stone on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau.

The surrounding area further underscores this long continuity of human activity. Extensive cultural heritage surveys have identified dozens of archaeological sites within a broad radius of the stone, dating from the Paleolithic period through to modern times. Rather than an empty, untouched wilderness, the plateau emerges as a long-used corridor of settlement, migration, and interaction — a landscape repeatedly traversed by travelers, herders, and envoys over thousands of years.

Today, as sunlight settles over the snow-covered peaks of the Three-River-Source region, the Garitang Engraved Stone stands as more than a relic of the past. It marks a pivotal shift in historical understanding, extending the western reach of the Qin Dynasty, grounding the Kunlun legend in physical reality, and revealing a civilization shaped not only by political unification, but by connection, movement, and shared cultural space. What began as a quiet message carved into an isolated rock has become a landmark discovery, transforming how the early history of China is understood, explored, and imagined.