Beneath the shifting waters of Alexandria’s eastern harbour on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast lie the drowned remnants of a once-splendid city—ports, palaces, and temples swallowed by the sea. Submerged by earthquakes and rising sea levels, these lost monuments have become the focus of surveys and excavations by the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology, in conjunction with Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

Much of the recent work has centered on Antirhodos Island, revealing a temple dedicated to the ancient Egyptian goddess Isis, which was renovated by Cleopatra VII, as well as the Timonium—a palace built by her partner, the Roman general Mark Antony.

The shipwrecks discovered in the Royal Port of Antirhodos tell the story of Alexandria’s transformation from a city defined by the wealth and extravagance of the Ptolemaic dynasty into an economic powerhouse of the Roman world.

The most recent excavations have uncovered a shipwreck dating to the early Roman period. Buried beneath the sand were the remains of a thalamagos, a type of Nile yacht with a colorful reputation in Roman literature as a “party boat.” However, the discovery of such a vessel in a busy commercial harbor was unexpected, prompting researchers to ask whether the wreck was being interpreted correctly.

Discovering the ship

The wrecks in the Royal Port were identified through a new high-resolution sonar survey of the seabed. This survey produced vast quantities of data, which were processed using a machine-learning algorithm trained to recognize the distinctive “signatures” of shipwrecks. The initial results were promising, with excavations of algorithm-generated targets revealing a small boat and a 30-meter-long merchant ship.

Together with a similar merchant vessel found in the early years of the project, these discoveries illustrate the increasing commercialization of the Royal Port during the Roman period.

At the outset of the 2025 mission, researchers were confident that the newly identified wreck was another merchant ship. However, with each dive, new evidence reshaped this interpretation, gradually revealing a vessel unlike the one originally expected.

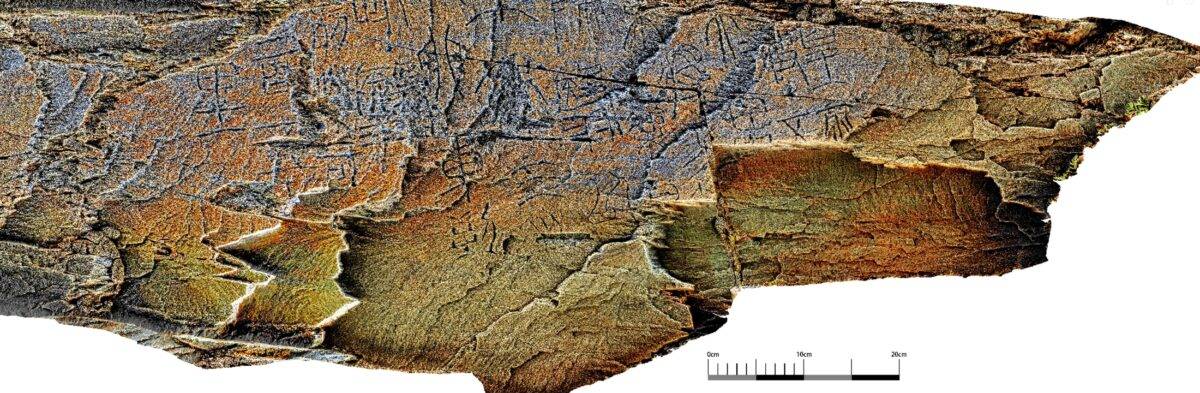

The wreck displays many features typical of Roman Imperial shipbuilding, yet Greek graffiti carved into its planks suggests that it was built and repaired in Alexandria. Its form also differs from the cargo vessels found elsewhere in the Royal Port. Measuring approximately 28 meters in length and 7 meters in width, the preserved remains indicate a flat-bottomed boat with a relatively wide, boxy hull. The bow and stern were asymmetrical, forming sweeping curves at each end. Notably, the vessel lacked a mast step, suggesting that it was propelled by oars rather than sails. These characteristics make it ill-suited for long-distance seafaring, deepening the mystery of its function.

Searching for clues in ancient texts

To better understand the vessel, researchers turned to roughly 500 fragments of Ptolemaic and Roman papyri documenting nautical activity. About 200 of these texts mention different types of river vessels, often named after the cargoes they carried, ranging from grain, wine, and stone to manure and corpses.

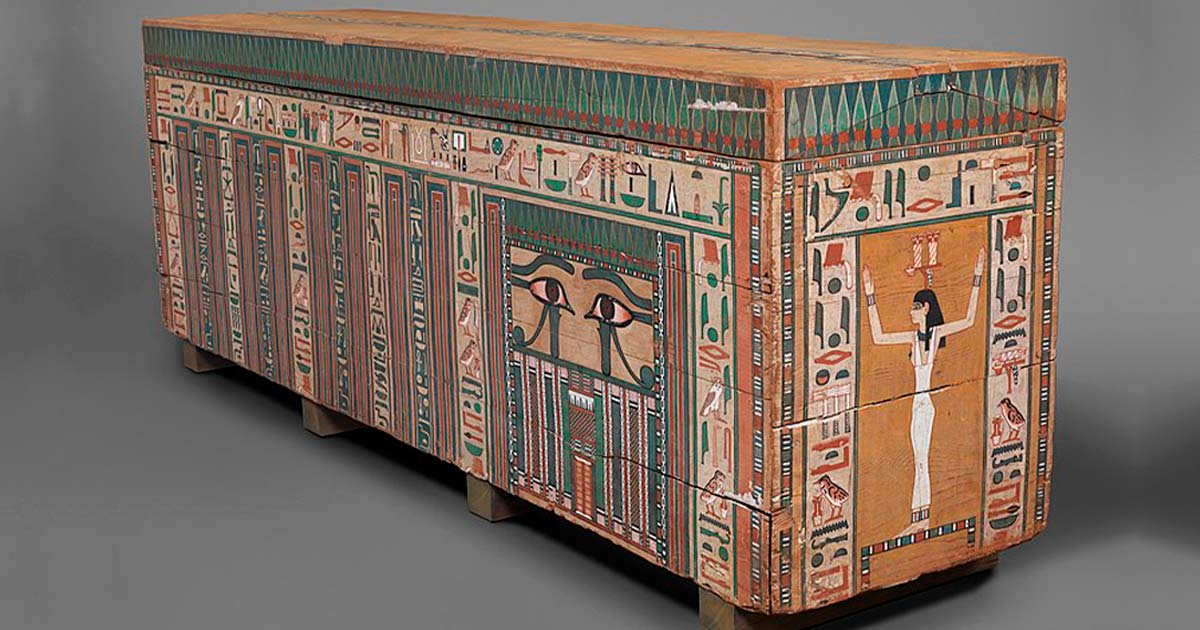

Among the less frequently mentioned vessels is the thalamagos, or cabin boat. This type of craft is depicted in the Palestrina mosaic, a roughly contemporary landscape scene discovered in a temple near Rome.

With its crescent shape and rows of oars, the mosaic vessel bears a striking resemblance to the remains uncovered in the Royal Port. While research on the wreck is still in its early stages, the evidence strongly suggests that it is indeed a thalamagos—one of the Nile’s infamous “party boats.”

What happened on ancient party boats?

The Palestrina mosaic depicts a cabin boat used for hunting hippopotami, a ritual associated with the pharaohs of ancient Egypt. The association of such vessels with royalty is echoed in the philosopher Seneca’s dismissive description of them as “the plaything of kings.”

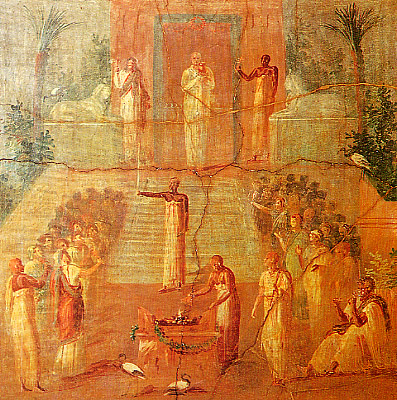

Although the Ptolemaic royal family owned luxurious Nile yachts, including oversized ceremonial versions, vessels of this size were likely common along the river. The ancient geographer Strabo described Alexandrians holding feasts aboard cabin boats in shaded waterways around the city, linking them to the revelry and licentious behavior associated with public festivals in the nearby town of Canopus.

However, Roman authors often exaggerated the luxury and excess of their recently defeated enemies to portray Ptolemaic society as decadent and morally corrupt. Interpreting the thalamagos solely as a party boat risks accepting this propaganda uncritically.

Administrative papyri present a more practical picture. Thalamagoi were not merely pleasure vessels; they could transport cargo and carry officials up and down the Nile. From this perspective, the presence of a cabin boat in a bustling commercial harbor is not entirely unexpected.

There is, however, another intriguing possibility. The vessel was found close to the temple of Isis and may have been destroyed in the same seismic event that caused the sanctuary’s collapse. This raises the question of whether it served as a ceremonial barge during festivals such as the Navigation of Isis.

This festival celebrated the “opening of the sea” after the winter season and sought divine protection for the grain fleet upon which Rome depended to feed its population. Although Strabo focused on the excesses of the festival’s participants, his account likely reflects Roman prejudice rather than the event’s true purpose.

Detailed post-excavation analysis of the wreck is now underway. Researchers aim to reconstruct the vessel’s original form, understand how it functioned on the Nile, and further examine ancient texts for additional clues. What is certain is that scholars are only beginning to uncover the secrets of this remarkable thalamagos.