Prasat Chan and Ta Mone Thom: Historical and Cultural Clarifications

Recent Thai narratives regarding Prasat Chan and the Ta Mone Temple complex reveal a profound misunderstanding of history, archaeology, international law, and accepted principles of cultural heritage conservation. More concerningly, they employ rhetorical strategies aimed at implying that Ta Mone Thom belongs to Thailand, despite the temple being situated within Cambodian sovereignty, as clearly established under international law.

1. “Khom” = Khmer

Contrary to claims in some Thai sources, the term “Khom” does not refer to a separate ethnic group or civilization. In historical, epigraphic, and archaeological scholarship, “Khom” is a later exonym used in Thai and Lao chronicles to describe the Khmer people and their civilization, particularly during and after the Angkorian period.

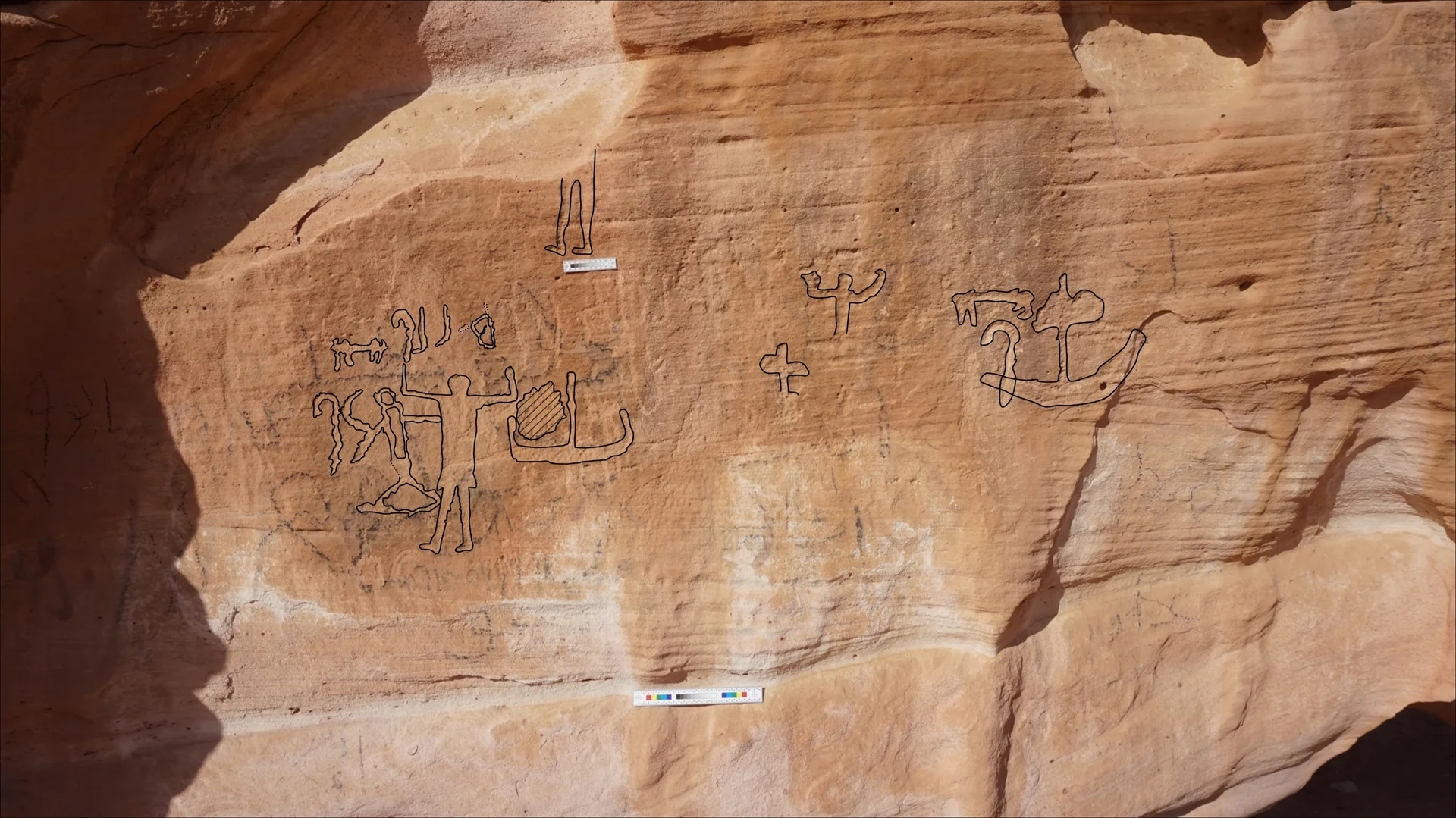

All so-called “Khom temples” are Khmer temples built between the 9th and 13th centuries. Evidence for their Khmer origin includes:

Sanskrit and Old Khmer inscriptions identifying Khmer kings, deities, and donors

Khmer architectural styles (Baphuon, Angkor Wat, Bayon, etc.)

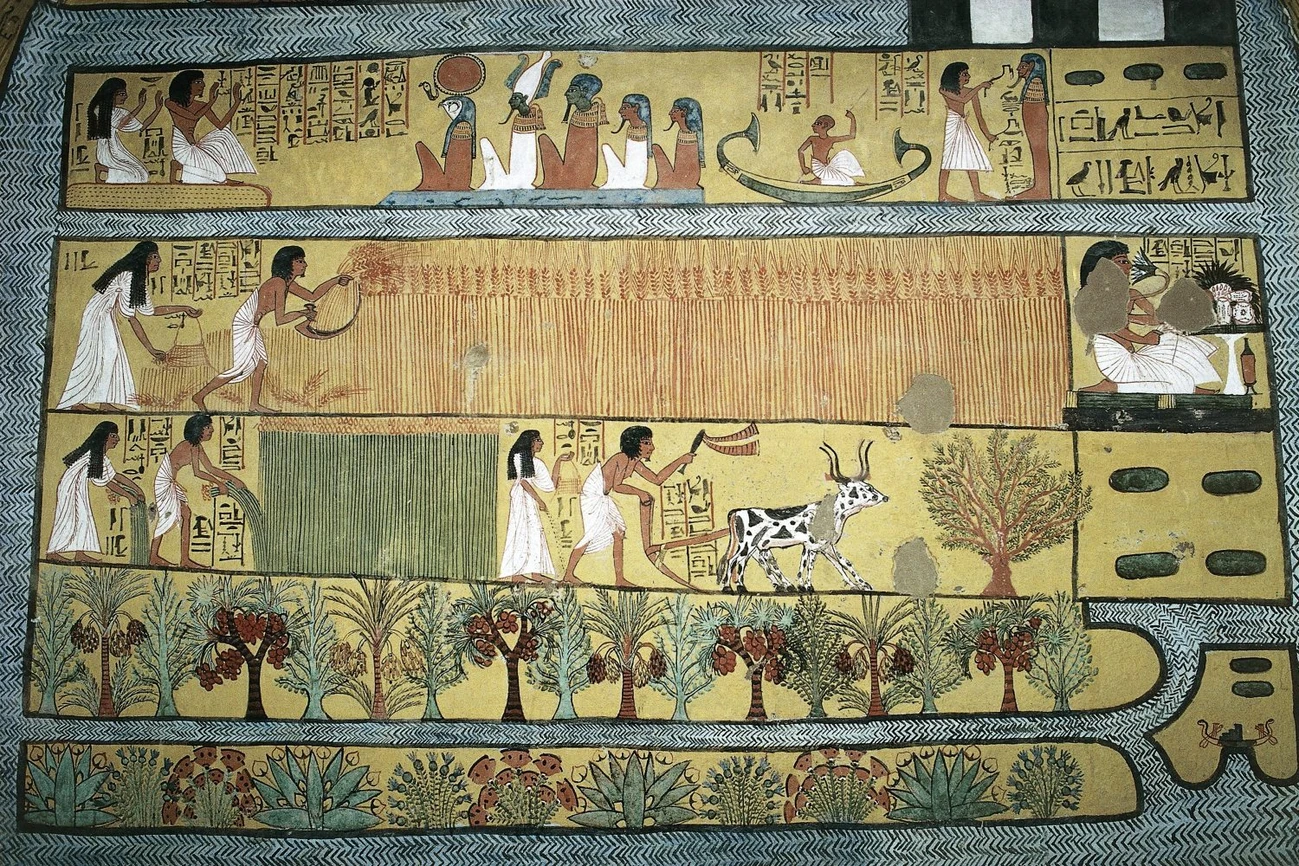

Hydraulic, symbolic, and cosmological planning consistent with Angkor

Integration into the Khmer imperial political, administrative, and religious system

Claims that modern Thai people are descendants of “Khom” while Khmer are not are historically false and unsupported by credible scholarship. Thai ethnogenesis occurred centuries later, shaped by Tai migrations and distinct state formation processes.

2. Thai Are Not Descendants of “Khom”

Historically, the Khmer civilization predates Thai kingdoms such as Sukhothai and Ayutthaya. Large parts of present-day Thailand were part of the Khmer empire during the Angkorian period. Thai states later adopted Khmer court practices, religious concepts, and administrative models, acknowledging their borrowing from Khmer civilization. The suggestion that Thai people are rightful heirs of “Khom heritage” is revisionist and serves political rather than historical purposes.

3. Misrepresentation Through Rhetoric

The Thai narrative equates modern reconstruction with historical legitimacy while portraying authentic ruins as evidence of neglect. This flawed reasoning suggests that Ta Mone Thom “belongs” to Thailand because it has been rebuilt, conflating restoration with ownership, modern construction with ancient heritage, and financial capacity with historical legitimacy.

4. Cambodian Sovereignty Over Ta Mone Thom

Ta Mone Thom is situated within Cambodian territory, as defined by the Franco–Siamese Treaties of 1904 and 1907. These treaties are internationally recognized, legally binding, and cannot be overridden by reconstruction or narrative manipulation.

5. Restoration Is Not Proof of Authenticity

Complete reconstruction that replaces original fabric destroys authenticity, even if visually impressive. In contrast, Prasat Chan, though in a ruined state, remains archaeologically authentic, stratigraphically intact, and a truthful record of history. Preservation of ruins is an ethical decision, not neglect.

6. Preservation Reflects Responsibility, Not Poverty

Modern heritage conservation prioritizes:

Choosing not to rebuild ensures historical integrity. Equating heritage value with financial capacity or cosmetic restoration misrepresents the principles of professional conservation.

7. Heritage Cannot Be Claimed Through Reconstruction

Cultural heritage legitimacy arises from history, archaeology, and sovereignty, not modern rebuilding. Prasat Chan and the Ta Mone complex are part of the same Khmer cultural landscape; legitimacy does not depend on visual completeness or tourism readiness.

8. Authentic Heritage Matters Most

Real heritage resides in original stones, placement, and uninterrupted historical truth. Prasat Chan preserves this authenticity. Rebuilt monuments may impress visitors, but ruins educate humanity. Khmer civilization is the builder of these monuments; history should be respected, protected, and presented honestly.

Heritage should serve humanity, not politics. Authenticity, not spectacle, must remain the guiding principle.