Introduction

Among the most intriguing religious phenomena of antiquity are the so-called mystery cults—secretive religious societies that flourished across the ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern world from the late Bronze Age through the Roman Imperial period. Unlike public civic cults, which were embedded in state ritual and communal identity, mystery cults were defined by secrecy, initiation, and personal religious experience. Their rites were restricted to initiates, their teachings transmitted orally, and their sacred narratives deliberately concealed from outsiders. This combination of exclusivity and promise of personal transformation has long fascinated historians and archaeologists alike.

Mystery cults were not marginal or fringe practices. They attracted participants from all social classes, including elites, merchants, soldiers, women, and enslaved individuals. Over time, they exerted a profound influence on religious thought, ritual practice, art, and philosophy within mainstream ancient culture. Although the secrecy surrounding their beliefs complicates interpretation, archaeological evidence—ranging from sanctuaries and inscriptions to ritual objects and iconography—has allowed scholars to reconstruct aspects of their structure, symbolism, and social function.

This article examines the mystery cults of the ancient world through an archaeological lens. It explores their historical background, material evidence, major cult centers, initiation rites, and broader cultural significance. It also considers modern scholarly approaches and debates, highlighting how ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of these enigmatic religious traditions.

Historical Background of Mystery Cults

The origins of mystery cults lie in the religious landscapes of the ancient Near East and Aegean world, where ritual secrecy and initiation were already established concepts. By the Archaic and Classical periods of ancient Greece, mystery cults had become a recognizable category of religious practice, distinguished by their focus on individual salvation, esoteric knowledge, and life after death.

The term “mystery” derives from the Greek mystērion, itself related to myein, meaning “to close” or “to shut,” often interpreted as closing the eyes or mouth. This etymology reflects the central role of secrecy: initiates were bound by strict prohibitions against revealing ritual content. Public knowledge of these cults was therefore limited to general themes rather than specific rites.

During the Hellenistic period and especially under Roman rule, mystery cults expanded dramatically. Increased mobility, urbanization, and cultural exchange facilitated the spread of religious traditions across regions. Egyptian, Anatolian, Persian, and Levantine cults found new adherents in Greek and Roman cities, often adapting their rituals to local contexts while preserving core symbolic elements.

Unlike state-sponsored cults, mystery cults typically transcended ethnic and political boundaries. Participation was voluntary, initiation-based, and centered on personal devotion rather than civic obligation. This flexibility allowed them to coexist with traditional religion rather than replace it, contributing to the complex pluralism of ancient religious life.

Defining Characteristics and Initiation Practices

Mystery cults shared several defining features, though practices varied considerably between traditions. Central among these was initiation, a ritual process that marked entry into the cult and granted access to its sacred knowledge. Initiation often occurred in stages, with preliminary purification rites followed by more advanced ceremonies reserved for higher initiates.

Initiates typically underwent symbolic experiences designed to convey religious truths through drama, imagery, and sensory engagement. Darkness and light, silence and sound, fear and revelation were frequently employed to create transformative psychological effects. These experiences were intended not merely to instruct but to induce profound emotional and spiritual change.

Another key characteristic was the promise of personal benefit. While public cults focused on maintaining harmony between the community and the gods, mystery cults emphasized individual well-being, protection, and hope for a favorable afterlife. Many cults articulated narratives of death and rebirth, often centered on a deity who suffered, descended to the underworld, and returned, offering initiates a model for their own spiritual renewal.

Despite their secrecy, mystery cults did not reject public religion. Most participants continued to engage in civic rituals alongside their initiatory commitments. The mystery cults functioned as complementary religious systems, addressing existential concerns that public worship did not fully resolve.

Archaeological Evidence and Methodological Challenges

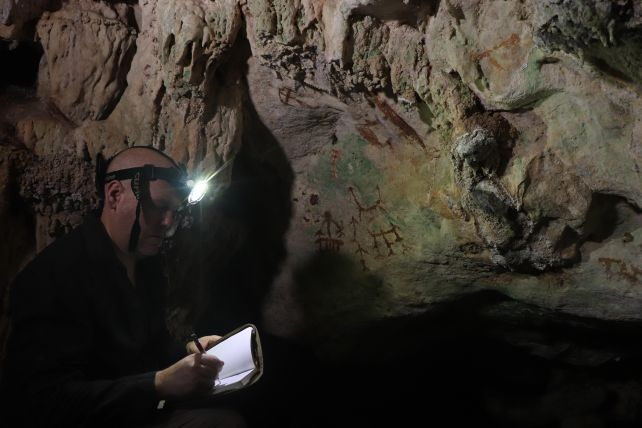

Archaeology plays a crucial role in the study of mystery cults, yet it also presents significant challenges. The intentional secrecy of these cults means that direct descriptions of rituals are rare. Most literary accounts come from outsiders, philosophers, or later critics, whose perspectives are often incomplete or biased. As a result, material evidence is essential for reconstructing cult practices.

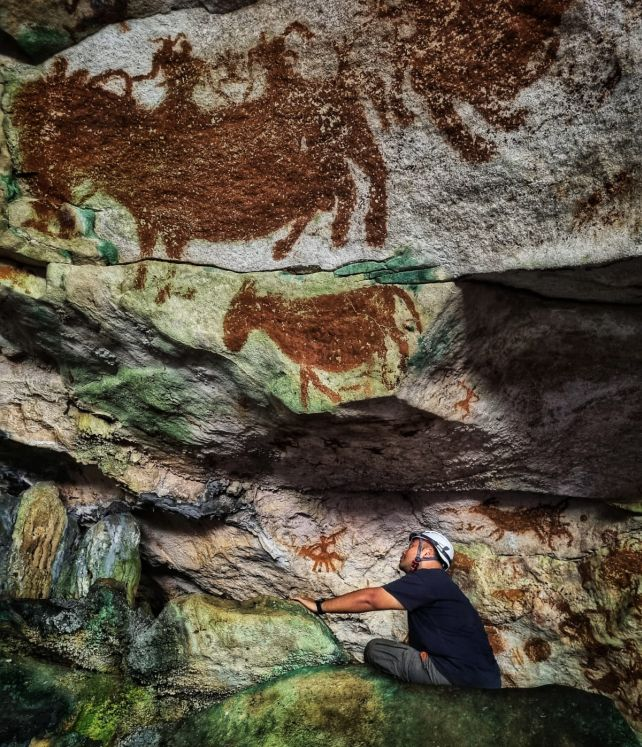

Sanctuaries dedicated to mystery cults are among the most informative archaeological sources. These sites often include specialized architectural features such as subterranean chambers, enclosed halls, or carefully controlled sightlines, suggesting ritual use. The spatial organization of these sanctuaries reflects the structured progression of initiatory ceremonies.

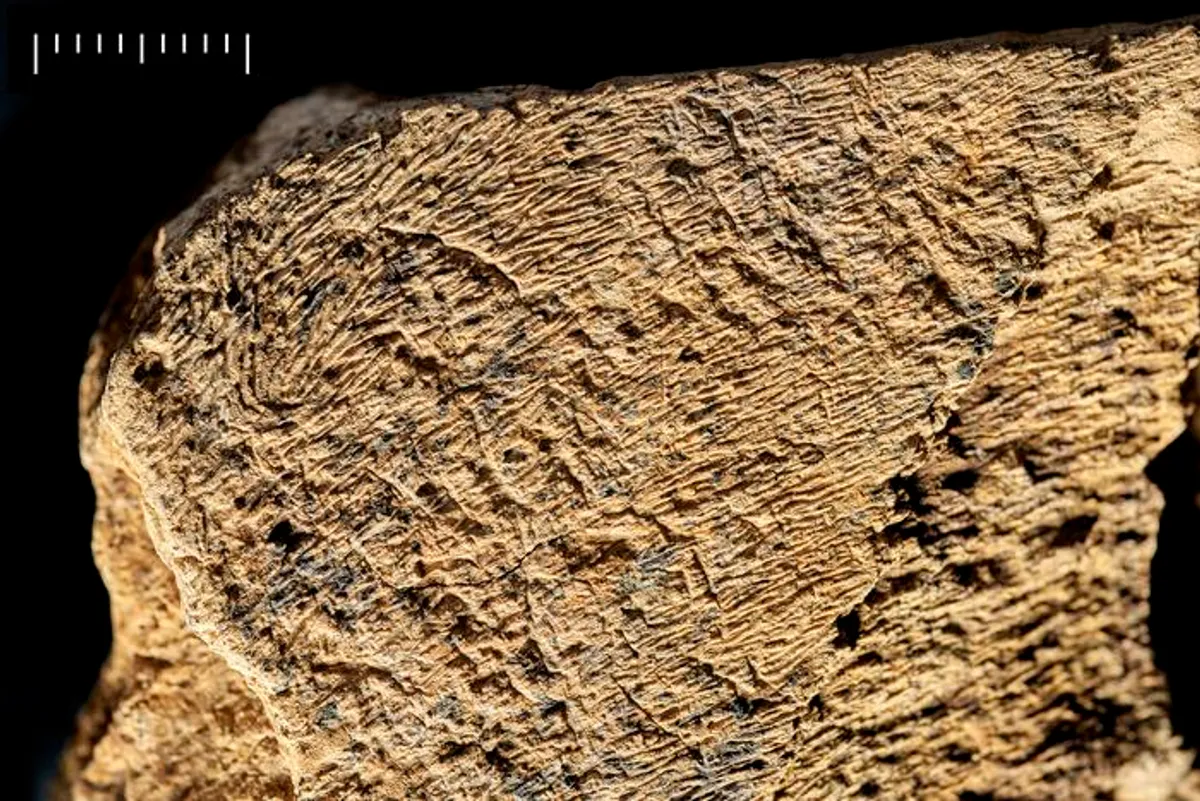

Inscriptions provide valuable information about cult membership, offices, and dedications. Although they avoid revealing ritual secrets, they often attest to the presence of initiates, priests, and benefactors, offering insight into the social composition of cult communities. Votive offerings, including lamps, figurines, vessels, and symbolic objects, further illuminate devotional practices.

Iconography is another critical source. Reliefs, mosaics, and wall paintings depict mythological scenes associated with specific cults, such as divine processions, sacred banquets, or moments of revelation. While these images are symbolic rather than literal representations of rituals, they convey core themes and theological concepts.

Dating these materials relies on a combination of stratigraphy, stylistic analysis, epigraphy, and scientific techniques such as radiocarbon dating where organic materials are present. The integration of these methods allows archaeologists to trace the development and spread of mystery cults over time.

The Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries, centered at Eleusis near Athens, are among the earliest and most influential mystery cults in the ancient world. Dedicated to Demeter and Persephone, the cult was closely tied to agricultural cycles and the myth of Persephone’s descent and return from the underworld.

Archaeological excavations at Eleusis have revealed a complex sanctuary that evolved over centuries. The Telesterion, a large hall designed to accommodate thousands of initiates, was the focal point of the rites. Its architectural scale indicates the widespread popularity and official support of the cult, which was integrated into Athenian state religion while preserving its initiatory secrecy.

Ritual objects associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries include ceremonial vessels, torches, and symbolic agricultural implements. Inscriptions and reliefs depict processions linking Athens to Eleusis, underscoring the public dimension of what ultimately culminated in secret rites.

Scholars generally agree that the Eleusinian initiation promised initiates a blessed afterlife, though the exact nature of the revelations remains unknown. The enduring prestige of the cult, which persisted for over a millennium, attests to its profound cultural and spiritual significance.

The Cult of Dionysus

The Dionysian mysteries centered on the god Dionysus, associated with wine, ecstasy, and transformation. Unlike the Eleusinian Mysteries, Dionysian rites were often characterized by emotional intensity and altered states of consciousness.

Archaeological evidence for Dionysian cults includes sanctuaries, inscriptions, and a rich corpus of iconography depicting ecstatic dances, ritual feasting, and mythological narratives. Sites such as Delphi, Athens, and various locations in southern Italy provide material testimony to the cult’s widespread presence.

Initiation into Dionysian mysteries likely involved nocturnal rites, music, and dance, designed to dissolve ordinary social boundaries and foster a sense of unity between participants and the god. These practices were sometimes viewed with suspicion by authorities, leading to periods of repression, particularly in Rome.

Despite this ambivalence, Dionysian symbolism deeply influenced art, theater, and philosophy. The cult’s emphasis on liberation and transcendence resonated with broader cultural currents, shaping conceptions of individuality and divine inspiration.

Egyptian Mysteries: Isis and Osiris

The mysteries of Isis and Osiris originated in ancient Egypt but gained immense popularity throughout the Greco-Roman world. These cults emphasized themes of death, resurrection, and divine compassion, embodied in the myth of Osiris’s murder and restoration and Isis’s role as a devoted spouse and powerful magician.

Archaeological evidence includes temples, statues, ritual vessels, and inscriptions found across the Mediterranean, from Egypt to Britain. Notable sites such as Philae, Pompeii, and Delos reveal how Egyptian religious traditions were adapted to diverse cultural contexts.

Initiation rites in the Isiac mysteries appear to have involved purification, fasting, and symbolic reenactments of the Osiris myth. Literary sources, supported by archaeological findings, suggest that initiates were promised spiritual enlightenment and protection in the afterlife.

The visual language of the Isiac cult, characterized by distinctive iconography such as the sistrum and the knot of Isis, became widely recognizable. This imagery influenced Roman religious art and contributed to the broader appeal of Egyptian religious concepts.

The Mithraic Mysteries

The cult of Mithras represents one of the most distinctive mystery religions of the Roman Empire. Primarily associated with soldiers and merchants, Mithraism was centered on the god Mithras and his symbolic slaying of a bull, known as the tauroctony.

Archaeological discoveries of Mithraea—small, cave-like sanctuaries—have been instrumental in understanding the cult. These structures, found throughout the Roman world, exhibit standardized layouts with benches for communal meals and reliefs depicting Mithras’s mythic deeds.

Artifacts such as inscriptions, lamps, and ritual vessels indicate a hierarchical system of initiation, with multiple grades through which initiates progressed. Astronomical symbolism, evident in iconography and architectural orientation, suggests a cosmological dimension to Mithraic belief.

Despite extensive material evidence, many aspects of Mithraic doctrine remain debated. Scholars continue to analyze the relationship between Persian religious traditions and Roman interpretations, emphasizing the cult’s adaptability and symbolic complexity.

Cultural Significance and Influence on Mainstream Religion

Mystery cults played a crucial role in shaping religious thought and practice in antiquity. Their emphasis on personal salvation, ethical transformation, and life after death influenced philosophical discourse and religious experimentation.

The integration of mystery cult symbolism into public art and literature reflects their broader cultural impact. Mythological themes associated with initiation and rebirth became common motifs, reinforcing shared values while preserving ritual secrecy.

In late antiquity, mystery cults contributed to an environment of religious pluralism that facilitated the emergence of new religious movements. While distinct from early Christianity, mystery cults shared certain structural features, such as initiation, communal meals, and narratives of salvation, which scholars have examined in comparative studies.

Modern Research and Scholarly Interpretations

Contemporary scholarship approaches mystery cults through interdisciplinary methodologies, combining archaeology, philology, anthropology, and cognitive studies. Advances in excavation techniques and scientific analysis continue to refine dating and contextual understanding of cult sites.

Recent research emphasizes regional variation and local adaptation, challenging earlier models that treated mystery cults as uniform systems. Scholars now recognize the diversity of practices and meanings within individual cults, shaped by social, political, and cultural factors.

Digital reconstruction and spatial analysis have also enhanced understanding of ritual environments, allowing researchers to explore how architecture shaped sensory experience. These approaches offer new insights into how secrecy, symbolism, and embodiment functioned within ancient religious life.

Conclusion

The mystery cults of the ancient world represent a complex and influential dimension of religious history. Through initiation, secrecy, and symbolic ritual, they addressed fundamental human concerns about identity, suffering, and the afterlife. Archaeological evidence, though fragmentary, provides a rich foundation for understanding their practices and cultural significance.

Far from existing on the margins, mystery cults were integral to the religious fabric of antiquity. Their ability to adapt across regions and cultures ensured their longevity and impact. As modern research continues to uncover new evidence and refine interpretations, the mystery cults remain a vital subject for exploring how ancient societies understood the divine and the human condition.