How the Babylonians Turned the Stars into a System That Shaped Civilizations

Astrology interpreting the heavens to understand life on Earth was not invented for personal horoscopes. In ancient Babylon, it was a serious science linked to religion, agriculture, and the fate of kingdoms.

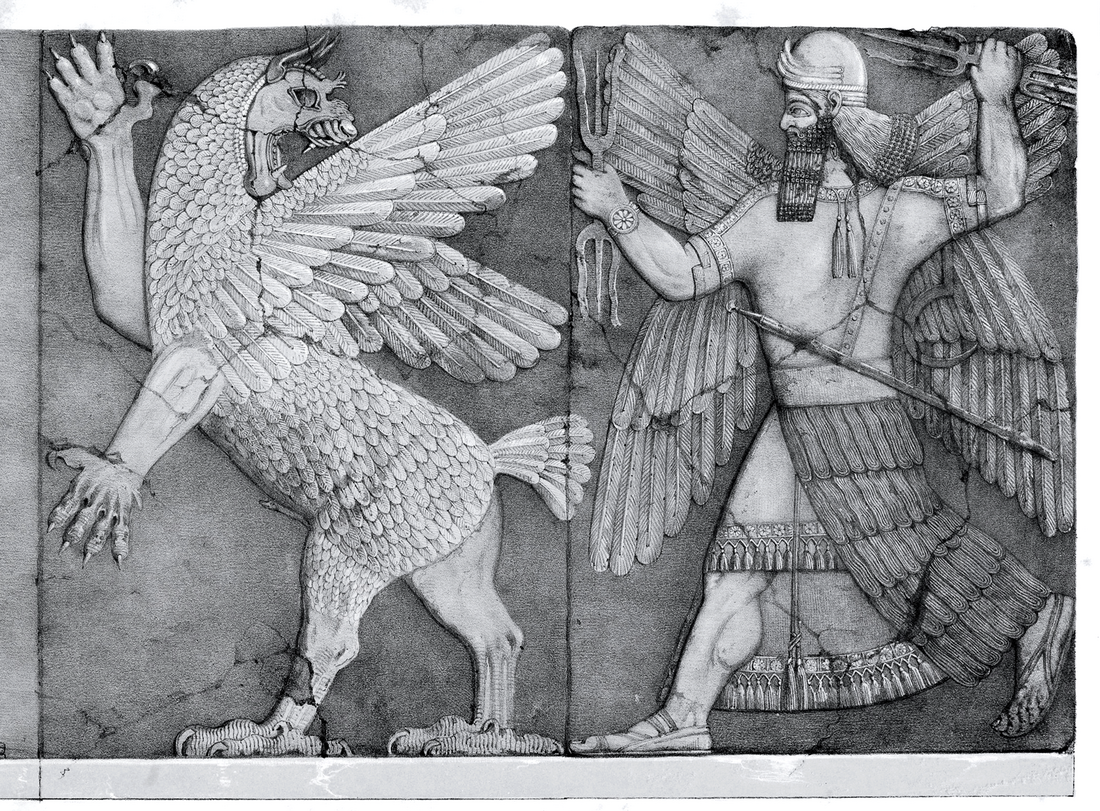

The Birth of Celestial Observation

Babylonian priests were among the first people to systematically record the positions of stars and planets. They believed the sky was a message board where gods communicated warnings, blessings, and signs. Clay tablets show centuries of detailed records, making Babylon one of the earliest centers of astronomical knowledge.

Astrology’s Role in Decision-Making

Kings relied heavily on astrologers. Before major decisions going to war, building temples, or approving laws they consulted experts who read omens in the sky. The movement of Venus, eclipses, and planetary alignments were believed to influence everything from harvests to political stability.

Ordinary people also depended on astrology for guidance, especially in farming, rituals, and medicine.

Influence on Later Civilizations

Babylon’s astrological system spread far beyond Mesopotamia. Greek scholars expanded it, Romans practiced it widely, and Islamic astronomers refined its mathematical foundations. Much of modern astrology, including the zodiac, traces its roots to Babylonian star lore.

A Legacy Written in the Stars

The Babylonians did not simply watch the sky—they interpreted it. Their work laid the foundation for astronomy and astrology, shaping the spiritual and scientific traditions that followed.

1034. The History of the First Written Peace Treaty

How Egypt and the Hittites Ended a War and Created a Model for Diplomacy

The Treaty of Kadesh is the oldest surviving written peace treaty, created after years of conflict between two ancient superpowers: Egypt and the Hittite Empire.

A War That Needed a Resolution

The Battle of Kadesh, fought around 1274 BCE, was one of the largest chariot battles ever recorded. Both sides claimed victory, but neither gained true control. After decades of tension, both empires faced threats from rivals and internal issues, making peace essential.

Crafting the First Known Peace Agreement

The treaty outlined shared borders, mutual support in case of foreign attacks, and the promise not to harbor fugitives. It was a remarkable step toward organized diplomacy.

Two versions of the treaty exist:

Each version presents the treaty in a slightly different tone, reflecting ancient propaganda and political pride.

Why the Treaty Matters Today

This document shows that ancient civilizations valued peace, negotiation, and international cooperation. A replica of the treaty is displayed at the United Nations to symbolize early global diplomacy.

A Landmark in Human Negotiation

The Treaty of Kadesh demonstrates that even in a world dominated by warfare, people sought stability through agreements—not just force.