Archaeologists in Jammu and Kashmir have discovered a 2,000-year-old Buddhist complex in Zehanpora village, Baramulla District, offering fresh insights into the Kashmir Valley’s early Buddhist history and its links to the broader Gandhara culture.

Announced after systematic excavation and survey work in 2025, the site revealed Buddhist stupas, monastic buildings, and urban-style settlement remains dating mainly to the Kushan period (1st–3rd centuries CE). The findings have gained national attention, with India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, calling it a “proud moment” that highlights Kashmir’s rich historical heritage.

Located on farmland along the Jhelum River, the site had long been marked by low mounds known to locals. While these features had occasionally attracted scholarly interest, their importance only became clear after recent technological and archival research.

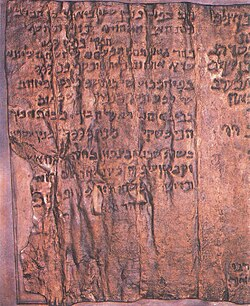

Officials say a breakthrough came when century-old, blurred photographs in a French museum archive were identified, showing three Buddhist stupas in the Baramulla region. During a monthly radio address, Prime Minister Modi noted that these “rare pictures… helped researchers connect the dots and confirm the historical importance of Jehanpora.”

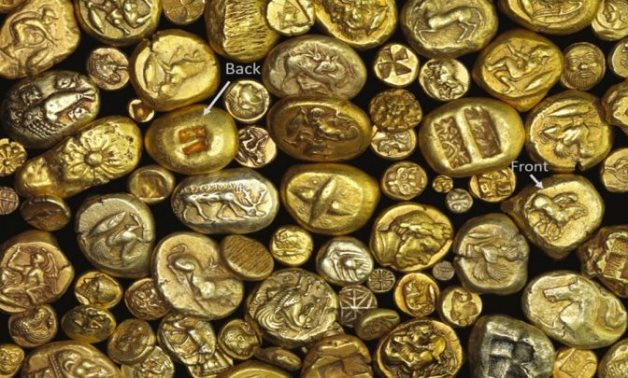

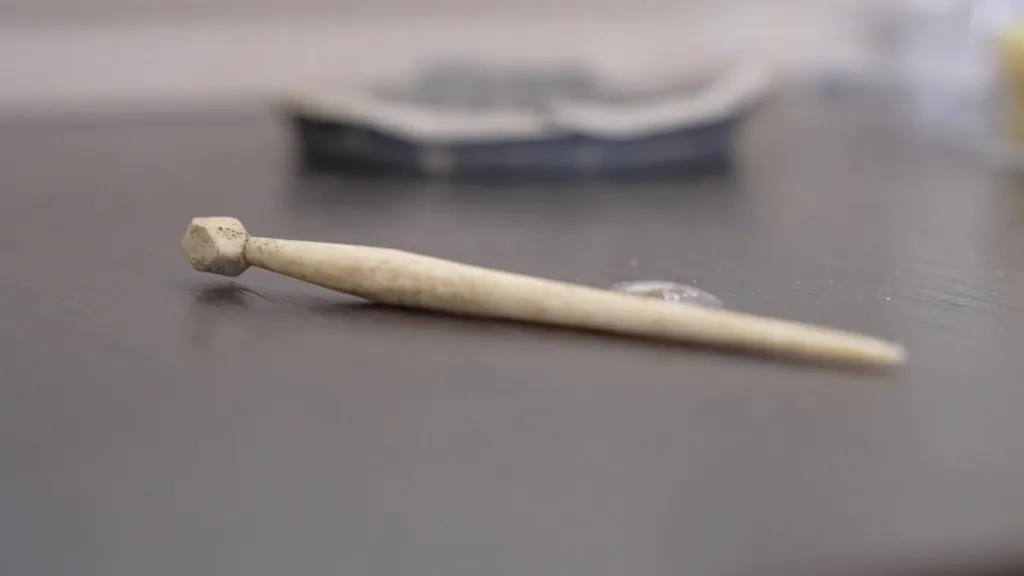

Subsequent drone surveys and aerial mapping confirmed that the Zehanpora mounds were manmade. Excavations revealed apsidal stupa foundations, monastic cells, pottery shards, copper artifacts, and stone walls, with layouts closely matching Gandharan Buddhist architectural styles.

The dig was a joint effort by the Department of Archives, Archaeology and Museums (DAAM), Jammu and Kashmir, and the University of Kashmir, with approval from the Archaeological Survey of India. Onsite work was led by assistant archaeology professor Mohammad Ajmal Shah under the supervision of DAAM director Kuldeep Krishan Sidha.

Excavation assistant Javaid Ahmed Matto described the discovery as “a matter of pride,” noting that both archaeological and literary sources, including accounts by the seventh-century Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, had long indicated Buddhism’s presence in Kashmir. Matto added that all recovered artifacts—pottery, copper items, and stone walls—belong to the Kushan period, and further stupas are expected to be unearthed.

Scholars say the Zehanpora findings firmly place Kashmir within the Gandhara Buddhist network, which connected regions of present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India through trade, pilgrimage, and monastic exchange. Harmeet Singh Soodan, head of the Political Science Department at Government Degree College, Katra, noted that the complex’s scale and layout suggest sustained patronage over centuries, supporting historical references to Kashmir as a center of Buddhist learning.